It may well be asked why the German

generals, many of them of aristocratic background with

centuries-long family traditions of military service to the

state, bowed to the authority of Adolf Hitler—a coarse,

low-born Austrian who’d served as a common soldier in the

Great War. Certainly there were many among them who looked

down on the Führer and his movement with scorn and distaste.

But however much they disapproved of him personally, the

generals found much to approve in his political program,

particularly where rearmament and foreign policy were

concerned. By and large the Generalität was prepared

to put up with National Socialism as long as it furthered what they viewed as the national interest.

It need hardly be said that for

most senior Army officers, that viewpoint was deeply

conservative. They had served the German Republic

grudgingly, “to prevent the worst from happening,” and they

looked forward to a day when something akin to the defunct

imperial regime might be restored. Thus when old President

von Hindenburg died on 2 August 1934 and the offices of

president and chancellor were fused in Hitler's person as

Führer and Reich Chancellor, very little trouble was made

over the oath that the armed forces were subsequently

required to take:

I swear to God this sacred

oath, that to the Leader of the German Reich and people,

Adolf Hitler, supreme commander of the armed forces, I

shall render unconditional obedience, and that as a

brave soldier I shall at all times be prepared to give

my life for this oath.

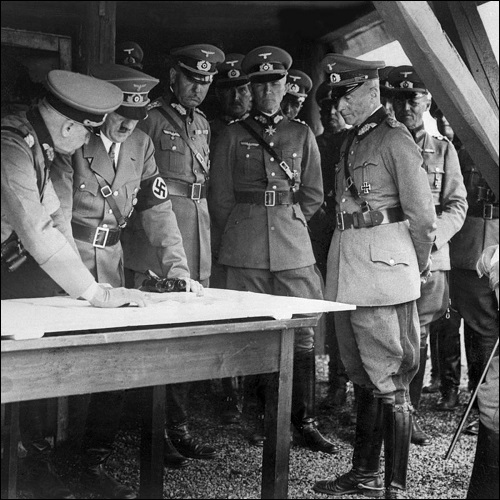

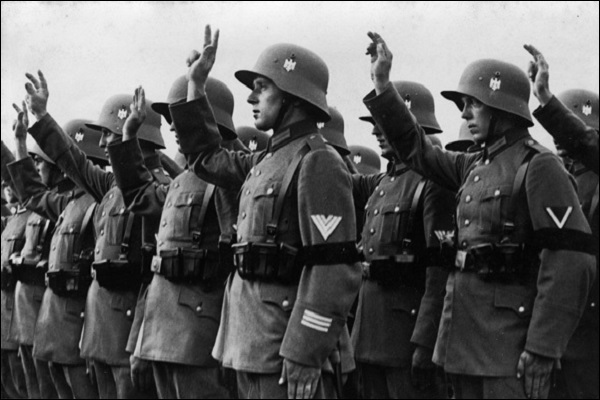

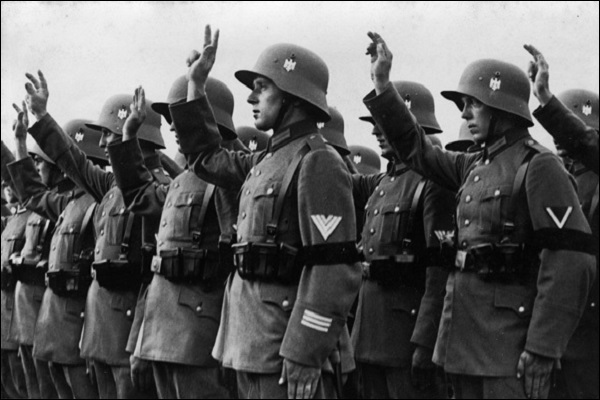

2 August 1934: German

soldiers take the oath of loyalty to Hitler (Bundesarchiv)

Contrary to what many people

assumed at the time, this oath was not imposed on the

military by Hitler. The initiative came from the Minister of

Defense, Colonel-General Werner von Blomberg, who hoped by

this means to draw the Führer away from the Nazi Party and

closer to the armed forces—the Army in particular. But it

turned out to have precisely the opposite effect and,

indeed, paved the way for the Army’s ultimate loss of

independence. Toward the end of World War II, when it was

clear to the generals that Hitler was leading Germany to

defeat and destruction, it was the oath to the Führer that

stayed their hand. Many were aware of the conspiracy that

culminated in the 20 July 1944 attempt on Hitler’s life, but with

very few exceptions the senior generals would not commit themselves to an active role against the regime.

Most German officers were no doubt

sincere in their belief that the oath taken in 1934 bound

them in obedience to the Führer. It was not, after all, an

unprecedented requirement. For nearly three centuries Prussian and German

soldiers had taken an oath to the Electoral Prince, then to

the King, and finally to the Kaiser.

The feeling that a sworn bond between the monarch and his

soldiers was right and proper had deep roots in German military

tradition. And without question, from 1934 on Hitler was a monarch in all but name.

The Führer, however, was no Prusso-German ruler in

the mold of Frederick the Great or even Kaiser Wilhelm II.

But the majority of officers were intellectually and

spiritually incapable of seeing past superficial

appearances. By and large, they believed themselves honor

bound to obey the supreme commander’s orders.

Moreover, as Germany rearmed and

the Army expanded, the character of the officer corps

underwent a profound change. Aristocratic Prussians remained

prominent in the senior leadership and on the General Staff,

but lower down men of quite different background began to

receive commissions. Many of these younger men—more and more

with each passing year—were ardent Nazis. And this suited

Hitler’s book, for he hated and distrusted the haughty

generals of noble blood who, he believed, merely tolerated

him and his regime. This general change in outlook was

reinforced by professional considerations. Rearmament

multiplied the career opportunities of all professional

soldiers, and there were few indeed who were willing to

jeopardize their chances of promotion by adopting a critical

attitude toward the Nazi regime.

That the Army’s professed concepts of honor

and duty were fundamentally incompatible with National

Socialism was first revealed to the officer corps in the

“The Night of the Long Knives” (June 1934) Hitler’s

liquidation of the troublesome leadership of the

Sturmabteilung (SA). Ernst Röhm, the SA Chief of Staff,

aspired to transform his brown-shirted stormtroopers into a

new people's army, absorbing the regular German Army in the

process. To this the generals were adamantly opposed and

they pressed Hitler to rein in his turbulent subordinate.

When he did so, employing terror and violence, using the

occasion to eliminate not only Röhm and the rest of the SA leadership but other

regime opponents as well, the Army stood by in readiness to

intervene against the stormtroopers if they tried a coup. And the fact

that two of the Nazis’ victims were brother officers—General

Kurt von Schleicher, who’d served briefly

as chancellor before Hitler’s appointment, and his former

aide, General Ferdinand von Bredow—did not seriously affect

their alliance of convenience with Hitler.

General Kurt von Schleicher (Photo:

Bundesarchiv)

Only a month

elapsed between the murder of Schleicher and Bredow, and the

oath of allegiance to the Führer. The officer corps was

sufficiently disturbed by what had happened to put pressure

on Hitler to rehabilitate the dead men and restore their

honor, and this he did, no doubt calculating that dead men’s

honor posed no threat to National Socialism. And there the

matter rested, the Army turning its attention to the

much more congenial task of rearmament.

Though few

realized it at the time, the Night of the Long Knives and

the oath pledging loyalty to Hitler sowed the

seeds of corruption and subjugation. The lesson was to be driven

home in the Blomberg-Fritsch Affair (early 1938) which

Hitler exploited to purge the Army’s upper ranks of skeptics

and solidify his own control of the armed forces. Once again

the Generalität

grumbled and protested but took no effective action.

Thus when the war began the stage

had already been set for a radical revision of the Army’s

relationship to the regime. In various ways the senior

generals had been compromised—some by ambition, some by a

perversion of patriotism, some by a narrow-minded conception

of duty, some by money. Perhaps most notoriously,

Colonel-General Walther von Brauchitsch, the

Commander-in-Chief of the Army, was indebted to Hitler for

considerable financial assistance in connection with his

divorce and remarriage. And when the early course of the war

made plain Hitler’s malign intentions, the German generals

found themselves poorly placed to protest or oppose the

murderous policies of their supreme commander.