● ● ●

The initial phase of the war on the

Eastern Front, from late June to early December 1941, made

it clear to both sides that the issue would not be decided

any time soon. Despite its spectacular run of victories, the

German Army’s advance had stalled at the gates of Leningrad

and Moscow. And despite the astronomical losses it had

sustained, the Red Army still possessed sufficient reserves

of men and material to stay in the fight.

By early December General of Army Georgy

Zhukov, commanding Western

Front, had largely succeeded in bringing the

German Army Group Center to a stop on the approaches

to Moscow. He believed, and persuaded Stalin, that the time

was ripe for a series of counterattacks to drive the enemy

away from the capital and, possibly, to set the stage for a

full counteroffensive. The counterattacks were duly launched

and they soon disclosed that the Germans were not merely

stalled but exhausted. Zhukov therefore decided, with Stalin’s

approval, to go for the big solution: the wholesale

destruction of enemy forces on the central sector of the

front. This Moscow counteroffensive was to evolve into the

Red Army’s first bid for decisive victory, and the first

test of the Red Army's ability to fight the deep battle.

Georgy Konstantinovich Zhukov

on the eve of war in 1941, when serving as Chief of the

General Staff and Deputy Minister of Defense (RIA

Novosti Archive)

The necessary reserves for a

counteroffensive were available: about ninety

rifle divisions, some

coming in from from the Far East and the Caucasus,

some newly raised. To supplement them numerous rifle

brigades, usually with three or four battalions plus a

slender ration of support units, were in process of

formation. Moreover, working with the energy of desperation,

the Red Army had succeeded in reconstituting its armored

forces, albeit on a modest scale. The new basic unit was the

tank brigade,

which was supposed to have 46 light and

medium tanks—though their actual strength was usually lower—plus a small motorized infantry battalion

about 500 men strong. As far as tanks were concerned, these

brigades were less than the size of a full-strength German

panzer battalion, though the addition of an organic infantry

contingent was a sound move. There were also many

independent tank battalions, with 20-25 tanks on average.

It was planned to combine these tank brigades and battalions

into division-sized units called

tank corps, but

nothing much could be done along that line before the Moscow

counteroffensive commenced.

Also introduced into the Red Army’s

order of battle was the

shock army. This major formation, intended to be

particularly strong in artillery and armor, was conceived as

the breakthrough force that would blow a hole in the German

defenses, clearing the way for exploitation by the mobile

forces. When first raised, however, First Shock Army and

Second Shock Army were little more than infantry armies

reinforced with such tank and artillery units as could be

scraped together. In late November, for example, First Shock

Army consisted of one rifle division, nine rifle brigades, a

few tanks battalions, an artillery regiment and a rocket

artillery battalion. Later on, however, the shock armies

became much more formidable.

7 November 1941: Red Army

troops march across Red Square on the anniversary of the

October Revolution (World War II Photos)

Some of these reinforcements had to

be committed to the defense of Moscow but others were used

to form a number of reserve armies. Thus Zhukov judged that he

had sufficient resources for his proposed counteroffensive,

particularly in view of the Germans’ increasingly parlous

situation—the onset of winter having caught them unprepared.

Bitter cold and deep snow immobilized the panzers, making it

next to impossible to conduct a mobile defense. Local Red

Army counterattacks had already compelled the Germans to

carry out successive tactical withdrawals—each of which

involved the abandonment of heavy equipment that could not

be moved along drift-choked roads. Frostbite casualties

multiplied. In the extreme cold even small arms, their

lubricants frozen, ceased to function. Often the only weapon

that could be relied upon to work was the hand grenade.

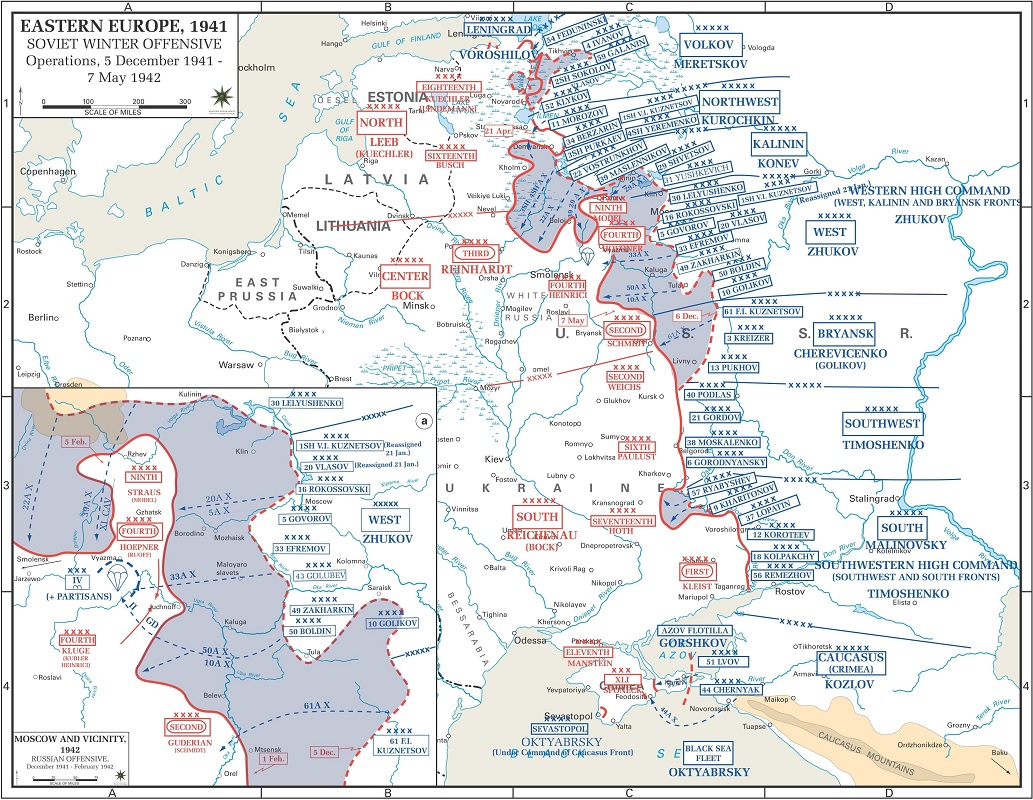

Zhukov’s plan envisioned two

attacks: one north of Moscow and one south of the capital.

Tactically, the situation was very favorable. The German

divisions, mostly understrength, were thinly spread over

long frontages. Reinforcements and supplies could reach them

only with difficulty via inadequate rail lines and

snow-covered roads. As the Red Army’s preliminary

counterattacks had shown, the enemy was too weak to keep his

front intact, and but marginally capable of conducting a

mobile defense.

The operational objectives of the

counteroffensive were to be the cities behind the German

lines that served as communications hubs and supply centers.

Prominent among them was Vyazma, about a hundred miles

southwest of Moscow. If it could be captured the entire

German Fourth Army would stand in danger of

encirclement and destruction. Thus everything depended on

the speed with which frontal breakthroughs could be made and

exploited.

In the northern sector the Red

Army’s counteroffensive began on the night of 4-5 December;

the attack in the south jumped off a day later. As expected

the German front proved porous. The tactical scheme was for

the Soviet infantry to overrun the German defensive

positions or, if possible, to infiltrate past them, opening

the way for the mobile forces. These were hastily organized

battle groups combining tank, cavalry and motorized

infantry units; their mission was to strike deep into the enemy’s

rear areas. But problems soon accumulated. As a directive

issued by West Front on 9 December complained:

Some of our units are pushing

the enemy back frontally instead of outflanking and

encircling him. Or they stand before the enemy’s

position, complaining about difficulties and heavy

losses. This gives the enemy time to withdraw to a new

line, regroup and organize his defenses afresh.

Thus, though the enemy was driven

back frontally, the decisive operational stroke miscarried.

Despite the gaps in their front the Germans managed to

retain their cohesion, and the hoped-for decisive

breakthrough was not achieved.

Even so the counteroffensive was a

great shock to the Germans. Material losses, particularly of

tanks, artillery and vehicles of all kinds, mounted with

alarming rapidity. Divisions shrank to the size of regiments

or battalions. As the defenders staggered under the Red

Army’s blows, the nightmare vision of Napoleon’s disastrous

retreat from Moscow in 1812 rose before their eyes. On 20

December, Colonel-General Erich Hoepner, commanding

Fourth Panzer Group, notified Army Group Center

headquarters that:

The commanding generals of

XXXXVI and V Corps have reported they cannot hold. Heavy

losses of trucks and weapons in recent days. They had to

be destroyed for lack of fuel. Weapons now 25-30% of

requirements. Only course to give orders to hold to the

last man. The troops will then be finished and there

will be a hole in the line.

Such alarming messages, suggestive

of looming defeat and accompanied by calls for a large-scale

withdrawal to some defensible line farther west, ignited a

command crisis—Hitler’s response to which was the summary

dismissal of numerous senior generals, the

Commander-in-Chief of the Army, Field Marshal Walther von

Brauchitsch, prominent among them. After sacking Brauchitsch

on 19 December, the Führer himself assumed command of the

Army and issued peremptory orders that the troops must stand

and fight. No further voluntary withdrawals would be sanctioned.

The Moscow

Counteroffensive and the General Offensive (Department of

History, USMA West Point)

Hitler’s stand-fast order certainly

stiffened his armies’ resistance and very possibly staved

off a debacle; on the other had it presented the attacker

with numerous opportunities to encircle and destroy

defending German units. But these opportunities the Red Army

proved unable to exploit. The problem was that the new,

hastily organized mobile battle groups lacked the requisite

punch and flexibility. They were too small, their commanders

were inexperienced and their constituent units were unused

to operating as a team. Thus many tactical opportunities

were thrown away and the enemy was given precious time to

regain his balance.

The fighting dragged on into the

new year as Stavka, at Stalin’s instigation, sought to

expand the counteroffensive into a general offensive along

the whole front. He lectured his generals that the Germans

were staggering after the battles west of Moscow; now was

the time to finish them off. Only Zhukov spoke against this,

arguing that the Red Army lacked the necessary means to make

such a gigantic operation possible. He proposed instead to

concentrate all efforts on the Moscow front, against

Army Group Center. As usual, however, Stalin had his

way. The general offensive was ordered. Its objectives were

to break the siege of Leningrad, complete the destruction of

the German forces facing Moscow, recapture the Donets basin

and liberate the Crimea. Reserves were committed on a large

scale and nine of the ten fronts (army groups) facing the

Germans were to be set in motion.

"Long live the gunners of the Red Army!"

Stalin directs his artillery (All World Wars)

But Zhukov’s forecast proved

correct and the general offensive fell far short of Stalin's

expectations. In the Leningrad sector nothing much was

achieved despite heavy fighting and high casualties; in the

south ground was gained but no decisive success was scored.

West of Moscow, the Red Army did come tantalizingly close to

encircling Army Group Center but

once again the Germans managed to stave off disaster—though

if Zhukov had had his way, things might have turned

out differently.

The Russian attacks became more and

more spasmodic as casualties, supply problems and German

resistance mounted. Ultimately, the Red Army proved unable

to bring off the hoped-for decision before the spring

thaw—the rasputitsa or season of mud—called a

temporary halt to all operations. Thus the general offensive

ended on a note of disappointment. To be sure, the Stalin

could claim a victory. The Germans had suffered high

casualties, lost much material and were driven back from the

gates of Moscow. But the enemy, though down, was not out.

Both tactically and operationally,

the Moscow counteroffensive and the subsequent general

offensive showed that the Red Army lacked both the tactical

expertise and the proper organization to fight the deep

battle. But out of the cauldron of the war’s first phase

there began to emerge cadres of commanders at all levels,

experienced and tested in battle. And the emergency

reorganization of the Red Army set in train by Stavka in

response to the initial defeats would put into the hands of

these commanders a military instrument in line with Soviet

capabilities—an instrument whose first test would come in

the 1942 summer campaign, culminating in the Battle of

Stalingrad.

● ● ●