● ● ●

At the beginning of the First World

War the airplane was viewed with skepticism by senior

military commanders—who thought that at most, it might be a

useful supplement to cavalry in the reconnaissance role.

But by Armistice Day 1918 the airplane had matured into a

formidable weapon of war. It first proved itself as an

instrument of tactical reconnaissance, a mission it carried

out far more

effectively than the cavalry. Each side therefore sought to

counter the other’s aerial reconnaissance activities by

developing armed pursuit aircraft, and soon these were engaging one another in air-to-air combat. Meanwhile the

larger two-seat reconnaissance and observation aircraft

acquired armament and assumed an active combat role, bombing

and strafing enemy ground targets. And if the enemy’s forces

in the field could be bombed, why not his rear

communications, war industries, railroads—even his cities?

This idea of using airplanes to

attack the enemy’s homeland was not a new one. It was a

staple of prewar fantastic fiction, for example in H.G.

Wells’ 1914 novel The World Set Free (which also

contained a prediction of atomic weapons). During the Great

War the first such air attack occurred on the night of 24–25

August 1914, when a German Zeppelin (airship) dropped bombs

on the Belgian city of Antwerp. The first sustained

strategic air offensive was conducted by Germany against

Britain between 1915 and 1918. These attacks were carried

out initially by Zeppelins, later supplemented by the twin-engine Gotha bomber,

which hand been specifically developed for the purpose. Though

it

caused comparatively little damage, German bombing

both outraged and alarmed the British government and public, and

caused significant resources to be diverted from the

fighting fronts to home defense.

The Allies in turn carried out sporadic

air attacks on cities in western Germany between 1915 and 1917,

and the idea of strategic bombing began gradually to gain

supporters. By 1918 Britain’s Royal Air Force (established

on 1 April of that year by amalgamating the Army’s Royal

Flying Corps with the Royal Naval Air Service) possessed a

strategic air arm in the form of the Independent Bombing

Force (IBF). Beginning in June of that year the IBF

conducted a strategic bombing offensive by day and night

against transportation and industrial targets in western

Germany. But these attacks coincided with the German Army’s

great final offensive on the Western Front, and the IBF was

frequently diverted from its strategic mission to provide

air support for the Allied armies.

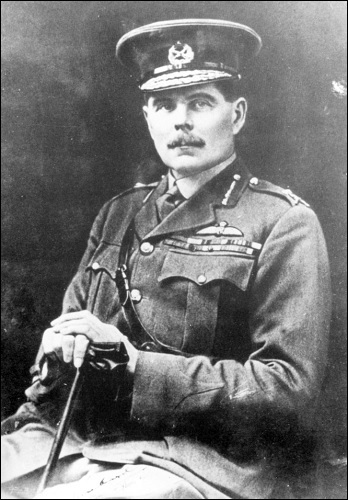

The Father of the RAF: Major-General Sir Hugh Trenchard,

Commander of the Royal Flying Corps 1915-17. He

became the first Chief of the Air Staff when the

RAF was established on 1 April

1918, then commanded the Independent Bomber Force, and

finally resumed the position of Chief of the Air Staff,

serving from 1919 to 1930. (Imperial War Museum)

As with the German raids on Britain

the RAF’s strategic bombing of Germany in 1918 caused no

very serious damage to German industries or cities, and many

aircraft were lost. But they were thought to have shown

promise and plans were drawn up for a much more powerful

effort in 1919—short-circuited by the collapse of German

resistance in the autumn of 1918.

The end of the war brought problems

for the RAF, its continued existence becoming a subject for

acrimonious debate. The Army and the Royal Navy had been

less than pleased to give up their air arms to the new

service and in the first years of peace there were repeated

calls, particularly from the Navy, for the abolition of the

RAF—supposedly as a cost-saving measure. Necessity is the

mother of invention, and to some extent sheer

self-preservation motivated the postwar RAF’s fervent embrace of the

doctrine of strategic bombing. In response to Army and Navy

arguments against the continued existence of their service,

the RAF’s leaders with the Chief of the Air Staff, Air

Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Trenchard, at their head, argued that

the future of war belonged to the air. The RAF, they

claimed, would take the fight directly to the enemy’s

heartland, destroying his war-making capacity and national

morale by bombing. Airpower would relegate the other armed

services to secondary roles.

But during the 1920s, parsimonious

defense budgets frustrated hopes for the creation of a strategic air

force. The requisite aircraft and infrastructure did not

exist and the British government, anxious to reduce defense

spending to an absolute minimum, would not give the

necessary money to develop them. Trenchard only kept the RAF

going by showing that air power could be a cost-effective

instrument for policing the empire. In Iraq and on India’s

Northwest Frontier, a few bombs usually sufficed to call

rebellious tribes to order, and most of the aircraft

procured for the RAF in the postwar decade were designed for

that mission.

Westland Wapiti light bombers

of the RAF over India's

Northwest Frontier Province, circa 1930 (Imperial War

Museum)

Even so, the concept of

strategic bombing, fostered by prophets of airpower like Trenchard, Billy Mitchell in the United States and Giulio

Douhet in Italy, captured the popular imagination. Arguing

that the airplane was destined to become the “winning

weapon,” they envisioned a massive aerial knockout blow that

would shatter the enemy’s war-making capacity and his will to

resist within days or even hours of a declaration of war.

This was an idea that came to be widely accepted. Science

fiction novels like Wells’ The Shape of Things to Come

and Olaf Stapledon’s

Last and First Men

presented just such alarming depictions of future wars—which

were all too credulously accepted.

More prosaically, debate in

military circles revolved around the validity of the airpower prophets’ vision. In Britain, for instance, there were

sharp disagreements over the likely effectiveness of air defenses:

fighter planes and antiaircraft guns.

Most RAF leaders argued that attack was the best defense and

that money would best be spent on

the strategic air arm. Others were not so sure, though Prime

Minister Stanley Baldwin, echoing Douhet, opined that “the

bomber will always get through.”

By

the mid-1930s, with Hitler in power, German rearmament

underway and the threat of a new European war looming larger

by the year, the debate over strategic bombing sharpened. The Nazi propaganda machine’s extravagant

claims regarding the newly established German air arm, the Luftwaffe,

tended to be uncritically accepted in other countries. The

frightful prospect of London and Paris laid in ruins by

bombs, their populations slaughtered in droves, was very

serviceable both to German diplomacy and to the French and

British antiwar movements. Yet frightening as they were,

such predictions of disaster failed to prevent the outbreak

of war on 1 September 1939. And as the sirens wailed in

London on the day that Britain declared war on Germany, it

remained to be seen how accurate they would prove to be,

when put to the test.

● ● ●