● ● ●

With operations in the Balkans

underway and the invasion of the USSR impending, the Blitz

came to an end in May 1941. Germany’s 1940-41 strategic air

offensive had failed to destroy the Royal Air Force, cripple

Britain’s industrial base or collapse national morale. To be

sure, British infrastructure and industry suffered

significant damage and some 41,000 civilians were killed.

But thanks to inadequate equipment, poor intelligence and

lack of strategic focus the

Luftwaffe had failed to deliver a knockout blow.

So Britain survived to fight on—but

fight how? The Army having been ejected from continental

Europe with no prospect of an early return, there seemed but

one way of striking at Germany directly, and that was

strategic bombing. Winston Churchill recognized this as

early as June 1940. Before the war he had been somewhat

skeptical of strategic bombing theory on both practical and

moral grounds. But now, writing to Lord Beaverbrook,

Minister of Aircraft Production, he struck a different note:

“When I look round to see how we can win the war, I see that

there is only one path…an absolutely devastating,

exterminating attack by very heavy bombers from this country

upon the Nazi homeland.”

These words, of course, were music

to the ears of the RAF’s senior leaders, who despite all

earlier disappointments remained convinced that strategic

bombing was the key to victory. Around the time that

Churchill was addressing the issue to Beaverbrook, Air Chief

Marshal Sir Charles Portal, then commanding Bomber Command,

wrote to the Deputy Chief of the Air Staff:

We [Bomber Command] have the

one directly offensive weapon in the whole of our

armory, the one means by which we can undermine the

morale of a large part of the enemy people, shake their

faith in the Nazi regime, and at the same time with the

very same bombs, dislocate the major part of their heavy

industry and a good part of their oil production.

Here was encapsulated the thinking

that would lead to the devastation of urban Germany and the

deaths of some 400,000 German civilians.

The Prime Minister watches

as a Short Sterling of No. 7 Squadron takes off on 6 June

1941 (Imperial War Museum)

But the results obtained during RAF

Bomber Command’s initial 1939-41 operations—far from

satisfactory—showed that the gap between theory and practice

remained wide. Heavy losses had ruled out precision daylight

bombing, and night bombing, though it reduced losses, proved ineffective. With the aircraft and technology

available it was extraordinarily difficult to locate and

bomb targets at night, even under ideal weather conditions,

and as late as May 1941, Bomber Command estimated that

35-50% of the bombs dropped by its aircraft were landing in

open country.

There were occasional successes,

such as Operation ABIGAIL-RACHEL against Mannheim on the

night of 16/17 November 1940. Its methodology foreshadowed

the much more destructive attacks of 1943-45. Some 200

aircraft took part, the whole force being led by a special

detachment of Wellingtons carrying a maximum load of 4lb.

incendiary bombs. The fires they started would, it was

hoped, enable the main force to locate the target. Weather

conditions and visibility were favorable, and two-thirds of

the attacking aircraft found and bombed the city. Seven

aircraft were lost.

Compared with earlier operations

ABIGAIL-RACHEL was judged a success, subsequent photographic

reconnaissance showing that considerable damage had been

done to various areas of Mannheim. On the other hand, the

bombs dropped had been widely dispersed and this reduced the

effectiveness of the attack. It was clear that more bombs,

better accuracy and a clearly articulated policy were

needed.

Then a bomb landed on the RAF, in

the form of the Butt Report. In August 1941 Churchill’s

chief scientific adviser, Professor Frederick Lindemann

(later Lord Cherwell), had commissioned D.M.B. Butt of the

War Cabinet Secretariat to conduct a statistical review of

Bomber Command’s attacks on German targets. Butt examined

some 650 photographs taken during 100 attacks on 28 separate

targets. The results were devastating. Butt estimated that

only a third of the aircraft claiming to have reached and

bombed the primary target had actually done so. Since around

65% of aircraft dispatched had claimed to have found the

target, this meant that on the average only a fifth of the

bombs dropped were hitting their intended target. Moreover,

since the target point was defined as a circle with a radius

of five miles, its size was 75 square miles—which in in most

cases encompassed a good deal of open country.

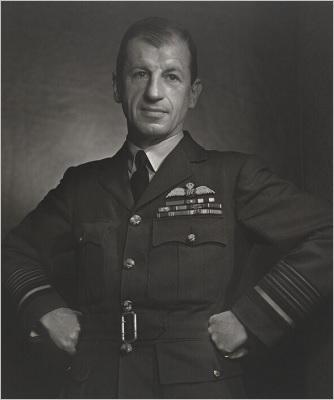

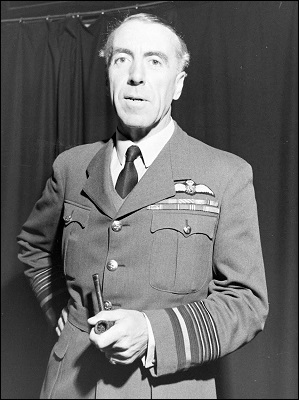

Left: Air Chief Marshal

Sir Charles Portal; Right: Air Marshal Sir Richard Peirse

(Imperial War Museum)

Sir Charles Portal, by then Chief

of the Air Staff, and his successor at Bomber Command, Air

Marshal Sir Richard Peirse, both thought that the Butt

Report exaggerated an admittedly unsatisfactory state of

affairs, but they could only agree with the Prime Minister,

who described it as “a very serious paper and seems to

demand your most urgent attention.” Churchill, indeed, had

grown somewhat skeptical of the RAF’s extravagant claims on

behalf of strategic bombing. In response to Portal’s claim

that with a force of 4,000 heavy bombers, Bomber Command

could totally destroy the forty or so largest German urban

centers, he wrote:

It is very disputable whether

bombing by itself will be a decisive factor in the

present war. On the contrary, all that we have learnt

since the war began shows that its effects, both

physical and moral, are greatly exaggerated…. The most

we can say is that it will be a heavy and I trust a

seriously increasing annoyance.

This can hardly have made pleasant

reading for Portal, Peirse and their RAF colleagues.

Over-pessimistic though it may have

been, the Butt Report served the purpose of focusing the Air

Staff’s attention on the problems of navigation, target

location and bombing accuracy by night. Hitherto, reliance

had been placed on dead reckoning and the sextant—which had

proved utterly inadequate. Now the search began for fresh

technological and tactical solutions, though it would be

some time before these were forthcoming.

Avro Manchester Mk I of

No. 83 Squadron

(Eugene W. Penick Memorial Collection)

Overall, 1941 was a year of

frustration for Bomber Command. Not only did its operations

yield unimpressive results, attracting sharp criticism from

the Prime Minister, but its expansion to the size deemed

necessary for improved performance proved exasperatingly

difficult. The great need was for true heavy bombers to

supplement and eventually replace the existing twin-engine

Wellingtons, Whitneys and Hampdens. Such aircraft had been

in development since 1936 but their service introduction was

much delayed by various teething troubles, especially as

rewards engines.

Great hopes had been vested in the

Avro Manchester, whose innovative design featured two

propellers, each driven by two engines with a common

crankshaft. It was a clever idea but the engine installation

proved unreliable and though the Manchester entered service

in late 1940 it never equipped more than eight squadrons and

was withdrawn from service within a year. The Short Sterling

was more successful, though it too had some significant

design issues. The Sterling had a short wingspan for its

size, which restricted its operational ceiling. And though

it could carry a heavy bomb load, the design of the bomb bay

was such that no bombs larger than 2,000lb could be

accommodated. The Sterling entered squadron service in early

1941 and soldiered on until late 1943, when more capable

heavy bombers became available in quantity.

One of these was the Handley Page

Halifax, which entered service in late 1941. Early versions

had performance problems due to insufficient engine power,

but once this was corrected the Halifax emerged as a most

effective heavy bomber. Finally there was the Avro Lancaster, one of the

war’s most outstanding combat aircraft. Its design was based

on that of the failed Manchester, albeit with a conventional

four-engine/four-prop power installation. The Lancaster

entered service shortly after the Halifax, and together they

played a major part in the transformation of Bomber Command

into the formidable force it became in the second half of

the war.

Flight

testing the second Halifax prototype, late 1940 (Eugene W.

Penick Memorial Collection)

One other ingredient was wanting in

the effort to guide Bomber Command through its time of

troubles: leadership. Sir Richard Peirse was a capable

officer who since his appointment in October 1940 had

grappled as best he could with a challenging set of

circumstances. But by the end of 1941 he was a tired man.

The disastrous night of 7/8 November 1941, when Bomber

Command lost almost 26% of the 143 aircraft that managed to

reach their targets, led to a virtual suspension of

operations—and there were many, Portal among them, who felt

that Peirse was losing his grip. Accordingly he was relieved

of command and transferred to the Far East, there to become

commander of Allied air forces in Southeast Asia and the

Southwest Pacific. His replacement was a man whose name was

to become synonymous with the devastation of urban Germany:

Bomber Harris.

● ● ●