● ● ●

Air Marshal Arthur

Harris—Bomber Harris to admirers and detractors alike—assumed command of RAF Bomber Command on 22 February 1942, at

a moment when doubts were growing about the conduct and very

purpose of the strategic air offensive against Germany.

Bomber Command's poor performance in 1941, culminating in

the disastrous night of 7/8 November 1941, had imposed what

amounted to an operational pause. Conservation became the

keynote: a buildup of forces with an eye to a resumption of

the strategic bombing campaign in the spring of 1942. But

skepticism was on the rise and it found its voice only three

days after Harris arrived at Bomber Command HQ in

High Wycombe. Speaking in Parliament on 25 February, Sir

Stafford Cripps, Lord Privy Seal and Leader of the House of

Commons in Churchill’s National Government, raised a

disturbing question: “Whether in the existing circumstances,

the continued devotion of a considerable effort to the

building up of this bomber force is the best use we can make

of our resources.”

Cripps pointed out

that the strategic air offensive had been launched at a time

when Britain stood alone “and it then seemed that it was the

most effective way in which we, acting alone, could take the

initiative against the enemy.” But now the Soviet Union and

the United States were ranged with Britain in a grand

alliance, and “Naturally in such circumstances the original

policy has come under review.” These comments struck the Air

Staff and Bomber Command HQ like a bolt of lightning, and

their effect was only partly dispelled when the Air

Minister, Sir Archibald Sinclair, told the House a few days

later that it was intended to resume bombing Germany at the

earliest possible moment.

But the skeptics made

no impression on the new Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief of

Bomber Command, who never for an instant wavered in his

belief that strategic bombing alone held the key to victory.

Sir Arthur Harris was, one might say, the last and greatest

of the air power prophets. His commitment to the strategic

air offensive was absolute; his attitude toward the other

fighting services bordered on the contemptuous. And in

addition he possessed (in the words of one historian of the

RAF) “the sure touch of a leader.” From the day of his

arrival at Bomber Command HQ, Harris’s energy and grip were

evident. The year 1942 had opened on a note of gloom. It

would end with a thunderclap.

Sir Arthur Harris with

aircrew of No. 460 Squadron, Royal Australian Air Force

(Australian War Museum)

At the time of

Harris’s appointment, a longstanding, fundamental question

about bombing policy remained to be resolved. Since 1940

there had been disagreements within Bomber Command and

the Air Staff over area bombing versus attacks on specific

industrial targets—the latter being official policy.

However, both Air Chief Marshal Sir Charles Portal, the

Chief of the Air Staff, and Harris’s predecessor at Bomber

Command, Air Marshal Sir Richard Peirse, argued in favor of

area bombing—on the pragmatic ground that only a whole

German city was a large enough target to be successfully

located and bombed. Ultimately their opinion carried the day

and while there was no formal change of policy, it was

tacitly accepted that area bombing of urban centers was the

only feasible option.

Harris himself had no

doubt that area bombing was the correct strategy, and he

soon found an ally in the person of Churchill’s chief

scientific adviser, Lord Cherwell. Early in 1942 he wrote a

paper for presentation to the Cabinet that advocated area

bombing of German cities. Cherwell argued that night bombing

was insufficiently accurate to be effective against

precision targets. Instead, the objective should be to

cripple German war production by “de-housing” industrial

workers. In plain language, German industrial workers and

their families were to be targeted. Churchill and the

Cabinet accepted this reasoning and it was embodied in a

formal Area Bombing Directive to Harris. He was enjoined “to

focus attacks on the morale of the enemy civil population

and in particular the industrial workers,” mainly in the

Ruhr, Germany’s largest industrial center.

A directive was one

thing; making it effective was quite something else. If not

moribund, Harris’s new command was in decidedly shaky

condition at the beginning of 1942. There were several

reasons for this: inadequate equipment, high losses, poor

results and, not least, the demands of other theaters of

war. Long-range aircraft were urgently needed for the Battle

of the Atlantic and Bomber Command itself was ordered to

devote much of its effort to minelaying and attacks on enemy

naval targets. In addition, bombers and aircrew were

required for the Middle East. The net effect of all this was

that in February 1942 only 20% of Bomber Command’s total

effort could be devoted to strategic bombing.

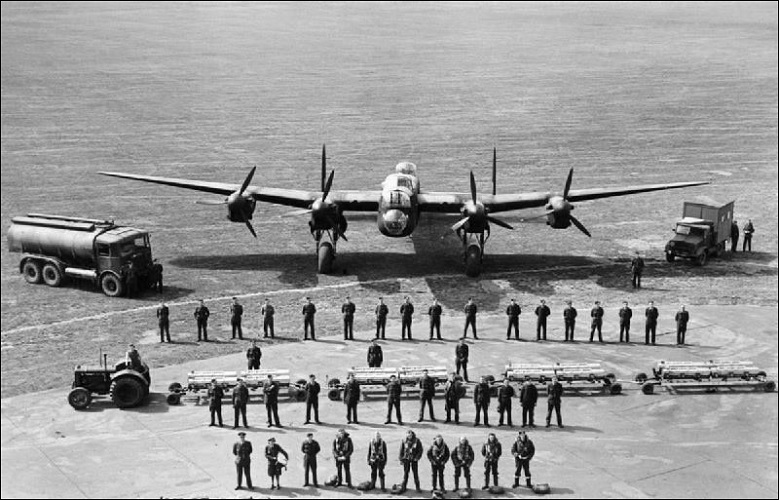

A Lancaster bomber with

its flight crew, ground support staff and load of 30lb

incendiaries (Imperial War Museum)

The equipment problem,

at least, was about to be overcome. The new four-engine

heavy bombers, the Handley Page Halifax and the superb Avro

Lancaster, were entering squadron service in early 1942, and

their numbers would grow steadily as the year progressed.

Along with them came new navigation aids. The first of

these, called Gee, was a radio system enabling a navigator to

calculate his bomber’s position by noting the time required

to receive signals from three separate ground stations.

Though Gee had its limitations, it at least promised to get

a bomber in the vicinity of its target. Another new item,

with ominous implications for urban Germany, was an improved

30lb incendiary bomb.

Early raids employing

Gee were directed at Essen in the Ruhr, and proved

disappointing. A first wave of Gee-equipped bombers carrying

flares led these attacks; it was their task to locate and

illuminate the target. They were followed by a second

Gee-equipped wave carrying a maximum load of incendiary

bombs. They were to mark the target by creating a

concentrated area of fire that the third wave, the main

body, could use as an aiming point. But even with Gee not

all of the illuminators and target markers bombed

accurately, and the false target points thus created misled

the main body. Though Gee proved a useful aid to navigation,

it was insufficiently precise for a challenging target like

the Ruhr.

Harris therefore decided

to shift Bomber Command’s attention to a different class of

targets: coastal cities. These had always been relatively

easy to locate, and with the help of Gee there were good

prospects for a successful attack. The first such city

selected was Lübeck on the Baltic coast, once the capital

city of the Hanseatic League. Admittedly it was not a

first-class strategic target, but Harris reasoned that it

was “better to destroy an industrial town of moderate

importance than fail to destroy a large industrial city.”

And Lübeck was attractive for another, sinister, reason: Its

Old Town was a warren of ancient wooden houses. This made it

“a particularly suitable target for testing the effect of a

very heavy attack with incendiary bombs,” as a Bomber

Command evaluation put it.

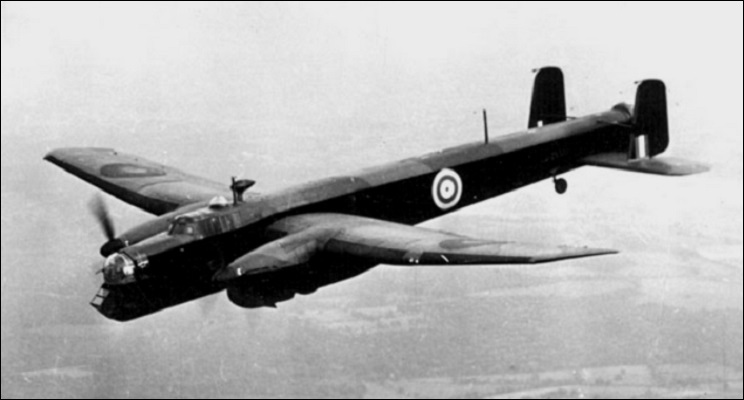

Lancaster

Mk I of No. 207 Squadron (Imperial War Museum)

Lübeck was struck on the

night of 28-29 March 1942, 234 aircraft being dispatched of

which about 200 located and bombed the target. They dropped

300 tons of bombs including 144 tons of incendiaries, which

destroyed around 50% of the city. In his diary, Goebbels,

the Nazi Minister of Propaganda, lamented that some 80%

percent of the historic Old Town had gone up in flames. But

only 312 people were killed, with around 800 more or

less seriously wounded and 8,000 made homeless—this out of a

population of 125,000. Still, Lübeck was an omen. A month

later Rostock, also on the Baltic coast, was hit on four

successive nights, and the results were devastating. More

than 100,000 people were made homeless; more than two-thirds

of the city were destroyed. The holocaust of urban Germany

had begun.

After Rostock the

operational tempo increased, but Bomber Harris was not yet

satisfied. He wanted an even more impressive demonstration

of Bomber Command’s might. Thus was conceived the MILLENNIUM

operation: 1,000 bombers against one target in one night. On

the face of things, such an attack seemed impossible. Bomber

Command’s average serviceability in the spring of 1942 was

such that it could muster 300-350 aircraft at most for daily

operations. But by extracting a maximum effort from the

front-line squadrons and using the aircraft of Bomber

Command’s Operational Training Units (OTUs) Harris was able

to assemble a force of 1,043 bombers: 553 Wellingtons, 131

Halifaxes, 88 Sterlings, 79 Hampdens, 73 Lancasters, 46

Manchesters and even 28 veteran Whitleys. MILLENNIUM would

commit virtually the whole of the RAF’s bomber force to

action.

Harris presented his idea

to Portal, the Chief of the Air Staff, on 18 May, and the

latter soon obtained Churchill’s enthusiastic approval. The

next full moon would come on May 30/31 and the attack was

scheduled for that night. The weather over Britain was good

but over Germany it was doubtful and of the possible targets

Harris ultimately selected Cologne, the Rhineland’s largest

city, as the most suitable.

MILLENNIUM was a

high-risk operation in more ways than one. Dispatching so

large a force, including as it did a large number of crews

whose training was incomplete, courted disaster: Heavy

losses among the OTUs would cripple Bomber Command’s

training base. The attack was planned to last no more than

90 minutes, which meant a high concentration of aircraft

over the target at any given moment—and a correspondingly

high risk of collision. And if the attack proved

unsuccessful the blow to British prestige would be very

great indeed. The decision to go forward showed Harris at

his best as a leader with the power to decide and command.

The Armstrong Whitworth

Whitley was the RAF's first monoplane bomber, entering

service in 1937. By the spring of 1942 it had been relegated

to training and other second-line duties but 28 Whitleys

assigned to Bomber Command OTUs participated in the

MILLENNIUM attack. (Royal Air Force photo)

The operation commenced

on a note of high tension. The weather over the North Sea

was bad, but conditions improved as the force made landfall

and the weather over Cologne was good. The fires raised by

the illuminators and target markers provided a fine aiming

point for the main body. Some 900 aircraft reached and

bombed the city, dropping 1,000 tons of incendiaries and 500

tons of high explosives. Not all bombers at this time carried

cameras, so an evaluation of the results had to await

subsequent air reconnaissance. This showed that the damage

was “heavy and widespread.” More than 600 acres of Cologne,

including 300 in the heart of the city, appeared to have

been completely destroyed. Once again, however, casualties

were light: 474 dead and 8,000 wounded, many of the latter

not seriously. On the other hand, more than 45,000 people

were made homeless, 36 factories were knocked out and 70

others had their production cut by half. All this was

temporary, of course: Throughout the war, the German home

front showed a remarkable ability to recover from such heavy

blows. Within a couple of weeks, life had returned almost to

normal in Cologne—a fact not appreciated at the time by

anyone in Britain, Harris included.

But by comparison with

Bomber Command’s early operations, MILLENNIUM was rated a great success. And the cost seemed not too heavy. All

told, 41 aircraft went missing: about 3.9% of the force

dispatched. Remarkably, only two were lost in a midair

collision over the target. Two more aircraft came down in

the sea on the return flight, two collided during landing

and five crashed on landing and had to be written off. A

total of 116 aircraft were damaged, twelve so seriously that

they had to be written off, and 33 seriously enough to

require prolonged repairs. Aircrew losses totaled 291 and

more were wounded in damaged aircraft and crashes.

On the very next night

another maximum effort dispatched 957 bombers to Essen and

this time the results were disappointing. So was an attack

on Bremen by 1,003 aircraft later in June. By then it was

becoming clear to Harris that the results of such large

raids did not justify the great effort required to mount

them, and he found himself in the awkward position of

explaining this to Churchill, whose appetite for such big

shows had been well and truly whetted.

Thus in the second half

of 1942 Bomber Command’s operational tempo was somewhat

reduced. Large raids of 500 to 600 bombers were still

launched on occasion, but much time was devoted to analyzing

the lessons of MILLENNIUM and its successors, integrating

new aircraft and weapons into the force, and refining

tactics. By the turn of the year Bomber Command would be a

much more formidable weapon, operating in partnership with

the US Eighth Air Force, whose advanced party arrived in

Britain in February 1942, and which commenced operations in

August. But only in retrospect did it become clear that with

the advent of Bomber Harris and the launch of MILLENNIUM,

the moment of balance was at hand.

● ● ●