● ● ●

The US Eighth Air Force commenced

operations in the summer of 1942, and during the year that

followed the stage was set for Operation POINTBLANK: the

Combined Bomber Offensive that would crush the Luftwaffe and

devastate urban Germany. For RAF Bomber Command, the prelude

to Pointblank was a period of consolidation. Though large

raids continued to be launched, the command’s operational

tempo slowed somewhat as new aircraft were introduced,

lessons were digested and tactics were refined. But for the

Americans, it was a baptism of fire and an opportunity to

show that the concept of daylight precision bombing was

viable.

The very first combat mission to be

conducted by Eighth Air Force was largely symbolic—as its

date, 4 July 1942, indicated. The mission was flown by the

15th Bombardment Squadron (Light) (Separate), whose

personnel had arrived in Britain without their own aircraft.

For the Fourth of July mission, the 15th borrowed a number

of Boston light bombers, these being the Lend-Lease version

of the A-20 light bomber with which the squadron was

intended to be equipped. The RAF provided invaluable

training to the 15th’s combat crews, six of which were

selected to join six RAF Bostons in a low-level attack

against German airfields in Holland.

Tactically, this first Eighth Air

Force mission was nothing to boast about. Only two of the

American Bostons bombed their assigned targets, two others

were shot down by flak (antiaircraft fire), and another was

badly damaged. But there was one notable incident. The

Boston piloted by Captain Charles Kegelman was hit by flak

that damaged its right engine and wing, lost altitude and

actually struck the ground. But the bomber bounced back up

and Kegelman managed to keep it in the air. Then, as he

turned for home, the guns of a German flak tower opened fire

on his plane. Kegelman turned, flew toward the tower and

shot it up with his nose guns. The German gunners ceased

fire and dived for cover. Kegelman then brought his damaged

Boston back to base, flying at very low altitude across the

English Channel. He was subsequently awarded the

Distinguished Service Cross. The 15th flew another combat

mission on 12 July, this time attacking at medium altitude

with no losses. Shortly thereafter its A-20s had arrived

from the United States and the squadron spent the next few

weeks making them operational.

The Hour Has Come:

Distinctive Unit Insignia of the 97th Bombardment Group

(American Air Museum in Britain)

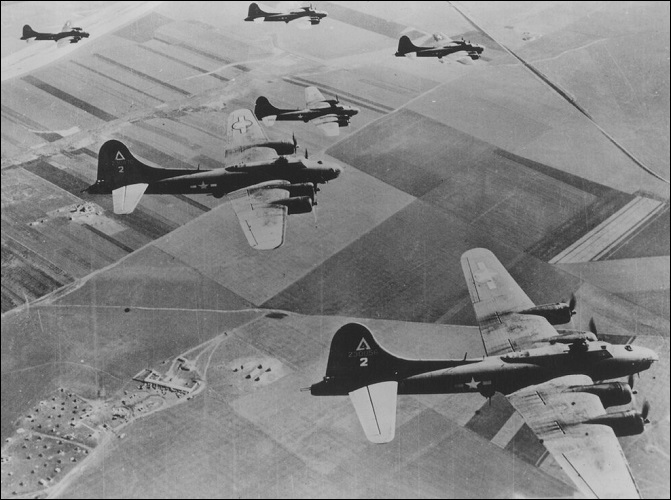

So the Americans entered the

battle—if only symbolically— as meanwhile the combat crews

of the 97th Bombardment Group (Heavy) completed their

training. By 15 August twenty-five crews were declared ready

for daylight bombing missions. The commitment of these crews

and their B-17s would mark the real beginning of the

American daylight bombing offensive and it only remained to

select a suitable target. At this stage an attack deep into

Germany itself was obviously out of the question; the target

would have to be within the range of fighter escort. The

choice fell on the Sotteville railroad marshaling yard at

Rouen in Normandy, an important transportation hub. The

attack would be delivered by twelve B-17s in two six-plane

flights, with another six flying a diversionary mission off

the coast. Nine Spitfire squadrons of RAF Fighter Command

would provide the fighter escort. The attack was scheduled

for 17 August, aircraft to begin taking off from Grafton

Underwood at 1530 hours. Major General Ira Eaker, now

commanding VIII Bomber Command, would ride along in

Yankee Doodle, lead bomber of the second flight.

Though small in scale, the Rouen-Sotteville

mission generated considerable attention, great excitement,

and not a little anxiety. For the 97th Bombardment Group, it

marked the end of a long and tedious period of training. For

the American commanders, Major General Eaker and Major

General Carl Spaatz, commanding the Eighth Air Force, it was

the moment when their theory of daylight precision bombing

would be put to the test. Numerous senior officers, British

and American, including General Eisenhower himself, were

present to see off the 97th on 17 July, along with a large

contingent of journalists.

The plan called for the B-17s to

bomb from an altitude of 23,000 feet. Visibility over the

target was good and all twelve B-17s were able to attack,

dropping a total of 36,900 pounds of high-explosive

bombs—about half of which hit the general target area. This

was considered good for a first effort and even those bombs

that missed the designated aiming points probably did some

damage, the target being a large one. Direct hits were made

on two transshipment sheds; ten or twelve of the twenty-four

tracks on the sidings were damaged, and some rolling stock

was destroyed, damaged, or derailed. Without doubt the

attack had inconvenienced the Germans, but it was clear that

to do lasting damage to such a target, a larger force of

bombers would be necessary.

The 97th met with slight opposition

on its first combat mission. Flak was minimal, slightly

damaging two B-17s. Only a handful of German fighters—Bf

109s—showed up, three of which attacked without result. No

US personnel were killed or wounded, with the exception of a

navigator and bombardier lightly injured when a pigeon

struck their aircraft, shattering the nose glass. None of

the six planes of the coastal diversionary flight were lost

or damaged. At precisely 1900 the first B-17 touched down at

Grafton Underwood, followed one after another by the

remaining seventeen. From Air Marshal Sir Arthur Harris,

commanding RAF Bomber Command, came this message for General

Eaker and his crews: “Congratulations from all ranks of

Bomber Command on the highly successful completion of the

first all American raid by the big fellows on German

occupied territory in Europe. Yankee Doodle certainly went

to town and can stick yet another well-deserved feather in

his cap.”

Post-attack photo showing

damage to the Sotteville railroad marshaling yard (HistoryNet.com)

It had been a successful mission,

though there were lessons to be digested. General Eaker

thought that formations had to be tighter, so as to maximize

the effectiveness of the B-17’s formidable defensive

firepower. He also advised that navigators and bombardiers

required additional training; the favorable weather

conditions attending the Rouen-Sotteville attack could not

always be assumed. As for the future, both General Eaker and

General Spaatz thought that some time must elapse before the

Eighth Air Force would be ready to strike at the German

heartland. For the time being, targets closer to home would

be attacked, gradually penetrating closer and closer to

Germany, the raids increasing in size as more heavy bomb

groups became operational.

But a long—and

unanticipated—apprenticeship lay ahead. Considerations of

grand strategy—the Pacific, Atlantic, the

Mediterranean—generated competing requirements for equipment

and trained air and ground crews that limited the scope of

Eighth Air Force’s operations. For this reason, the

full-scale Combined Bomber Offensive had to be postponed to

the summer of 1943. The operations conducted in the meantime

were too small in scale really to test the theory of daytime

precision bombing or produce decisive strategic results,

though they were most useful in refining tactics and

building up a cadre of experienced aircrew. Even so, the ten

months from Rouen-Sotteville were frustrating ones for

American airmen. Prewar planning had envisioned that a

strategic air offensive would be the first heavy blow

struck by the United States against Nazi Germany: the

essential prelude to a cross-Channel invasion and the total

defeat of the enemy. Now it was on hold.

By the autumn of 1942, the Eighth

Air Force embodied VIII Bomber Command, VIII Fighter

Command, VIII Composite Command (training) and VIII Service

Command (logistics). VIII Bomber Command had three wings,

each with two or three heavy bombardment groups. As these

became operational, more missions were able to be

flown — usually small in scale, invariably against targets

in occupied Europe on or near the coast. RAF Fighter Command

continued to provide most of the fighter escorts. German

opposition from flak and fighters was generally light, but

on 21 August came the first serious clash with the

Luftwaffe. A B-17 formation that had become separated from

its fighter escort was attacked over Holland by some

twenty-five Bf 109s and Fw 190s. In the twenty-minute battle

that ensued, the pilot and co-pilot of one B-17 were

wounded—the latter so seriously that he later died. B-17

gunners claimed two enemy fighters destroyed, five probably

destroyed, and six damaged, claims that were almost

certainly inflated. The German pilots, apparently impressed

by the bombers’ defensive firepower, did not press home

their attack. But 21 August was an omen. From then on the

Eighth encountered persistent, increasingly heavy fighter

opposition.

An Fw 190A-3 fighter of

Jagdgeschwader 2 "Richthofen" based on a French

airfield, late 1942 (Bundesarchiv)

On 6 September, 41 B-17s of the

97th BG and the newly operational 92nd BG attacked the

Avions Potez aircraft factory at Meaulte in France. Despite

a subsidiary attack on the nearby

Luftwaffe base, intended to keep enemy fighters on

the ground, the main mission ran into stiff resistance,

mostly from Fw 190s. Several were claimed destroyed or

damaged, but two B-17s were lost.

Still, the Eighth Air Force’s early

missions appeared to show that the concept of daylight

precision bombing was viable. Bombing accuracy had been fair

to good, with significant damage to targets. The B-17E

proved robust and well capable of defending itself, and

losses had so far been light. The stage seemed set for

further development of a European strategic air offensive.

But in late October 1942 the Eighth received a new directive

from General Eisenhower. With the invasion of French North

Africa — Operation TORCH — impending, great numbers of

troops and huge amounts of material would be moving by sea

from Britain to North Africa. It was vital to protect those

convoys from both U-boat and air attack. Eisenhower

therefore directed the Eighth to prioritize attacks on the

German Navy’s U-boat bases on the Atlantic coast of France:

Lorient, St. Nazaire, Brest, La Pallice, and Bordeaux.

Shipping and docks at Le Havre, Cherbourg, and St. Malo came

second, along with aircraft factories, repair facilities and

airfields. Transportation and industrial targets were

relegated to third place.

This directive was received by the

American airmen with mixed emotions. By shifting the

Eighth’s mission to the support of TORCH, it effectively put

the strategic air offensive against Germany on the back

burner. On the other hand, the heavy bombers were now

knitted into the fabric of Allied grand strategy. The “war

against the sub pens” would remain the focus of Eighth Air

Force operations until the spring of 1943.

● ● ●