Of the major belligerents in 1914, the Habsburg Monarchy

(Austria-Hungary) was the militarily the weakest, and its

army's performance in World War I was decidedly

mediocre—though not quite so bad as is often alleged. Most

of the Austro-Hungarian Army's problems were derivative of

the polity it served, though it must also be noted that the

Army’s senior commanders were, with the occasional

exception, none too competent. The troops themselves were

capable of fighting well if properly armed and competently

led—which all too often they were not.

The Army, like the Habsburg Monarchy itself, was a salad

bowl of nationalities and this presented serious problems, particularly

in the area of language. Since regiments were organized

along “national” lines, career Army officers had often found

it necessary to learn three, four or even six languages in

addition to their native tongue. Conrad von Hötzendorf, the

Chief of Staff in 1914, spoke seven languages. But

by the early twentieth century this traditional professional

standard had been abandoned in practice if not in principle.

The majority of officers were German Austrians and most of

the rest were Hungarians. These men resented having to

learn the languages of the troops they commanded—Croats,

Czechs, Bosnian Muslims, Poles, Slovaks, etc.—and did their

best to evade the requirement. Instead they relied on the “language

of service”: the few hundred German words that the troops

were made to learn so that they’d understand when their

officers spoke of rifles, sabers, cannons, etc. It was a

situation unlikely to foster organizational cohesion, nor

did it.

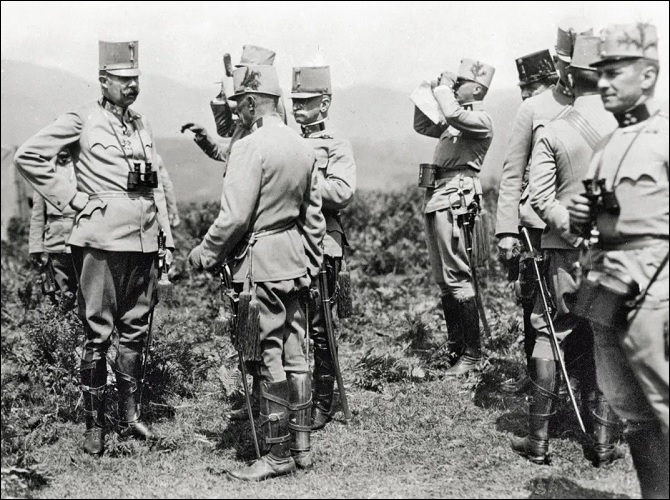

A general of the

Austro-Hungarian Army (left) and his staff

(Heeresgeschichtliches Museum)

This fundamental problem of ethnicity was compounded by

the Austro-Hungarian Army’s administrative and

organizational deficiencies. The Army was small (48 infantry

divisions, 8 cavalry divisions) and poorly equipped—this despite the fact that

the empire had a population of 50 million and a reasonably

well-developed industrial base. But the politics of

"dualism"—the unstable, uneasy relationship between Vienna

and Budapest—tended to stifle military reform projects. Army

reform was proposed from time to time but the Hungarians,

determined to maximize their autonomy, consistently refused

to give the necessary money. Nor was conscription,

supposedly based on a universal liability for service, very

strictly enforced. Finally, both the administrative machinery

of the Army and its high command were notoriously inefficient.

Thanks to dualism the Habsburg Monarchy had not one army but

three: the Imperial and Royal Army (kaiserlich und

königliche or k.u.k Armee) informally called the

Common Army, maintained jointly

by Austria and Hungary, the Austrian Landwehr, and the

Hungarian Honvéd. The Hungarians, jealous of their

autonomy, persistently opposed increased funding for the

k.u.k Armee, preferring to spend money on the Honvéd

instead. Nor did the Army possess any real reserve

divisions, conscription having been applied with

insufficient rigor to build up the necessary trained

manpower. Adolf Hitler was one of many Austrian subjects who

found it easy to dodge the draft. So in 1914 the pool of reservists was only

sufficient to bring the existing divisions up to war

strength and to replace initial losses.

Command flag of a field

marshal of the Austro-Hungarian Army

The tripartite nature of the Army also had the

unfortunate effect of complicating the structure of the

infantry division. Infantry regiments of the k.u.k Armee

had four battalions, whereas those of the Landwehr

and Honvéd had only three. Thus a division could have

as few as twelve or as many as sixteen battalions, depending

on the identity of its four regiments; the average strength

was fourteen battalions. The division's artillery brigade

was also variable in size and quality. Usually there were

two regiments: one with field guns and one with field

howitzers. The former usually had four batteries, each with

six guns; the latter usually two batteries, each with six

howitzers. But the number of batteries varied and some divisions had no howitzer regiment

at all. Moreover, Austrian guns and howitzers were mostly

outmoded, made of heavy bronze/steel alloy, with primitive

recoil systems and roughly half the range and rate of fire

of comparable German and Russian artillery.

In 1914, therefore, the Army as a whole was ill prepared

for war. Infantry training was primitive and the artillery

was armed for the most part with a miscellany of obsolete

weapons. Tactically, far too much faith was placed in

cavalry, which was in any case poorly trained for

reconnaissance, the only useful role it still had on the

modern battlefield. The result was a string of costly and

humiliating defeats in the first year of the war. German

assistance staved off a complete collapse but the Army’s

battle capacity had been gravely undermined and it never

fully recovered. By 1917 it was operating on the Eastern

Front as a mere auxiliary of the German Army, often under

direct German command.

Stoßtruppen

(assault troops) of the Austro-Hungarian Army in 1917

(Imperial War Museum)

Though tales of mass surrender and desertion were

exaggerated, the Army’s Slav troops grew increasingly

unreliable as the war wore on. Czech soldiers in particular

were bitterly resentful of the disdain with which their

mostly German Austrian officers treated them. Often the

reliability of a given unit depended on which enemy it was

fighting. Croat troops, for instance, generally fought

harder against Italy, the hated “hereditary enemy,” than

they did against the Russians.

Still, the Austro-Hungarian Army gave a better account of

itself than might have been expected. Italy entered the war

in 1915 at a moment when the Habsburg Monarchy’s military fortunes

were at their nadir. Coveting Austrian Trentino, the city

of Trieste and the eastern Adriatic litterol, the Italians anticipated a quick victory. But

the Austro-Hungarian Army fended off no fewer than eleven

Italian offensives between 1915 and 1917—this despite the

fact that it was always outnumbered. In 1917, with a

reinforcement of German divisions, the Austrians launched a

counteroffensive that demolished the Italian Army and very

nearly knocked Italy out of the war.

But this last victory came to nothing. The process of

disintegration set in motion by the stress and strain of war

had so far advanced by 1917 that nothing could save the

Habsburg Monarchy and its Army. The former’s collapse in

October 1918 was swiftly followed by the latter’s

dissolution.