● ● ●

NOTE ON UNIT

NOMENCLATURE

By the

late 1930s tank battalions of the British Army were either

former horse cavalry regiments or belonged to the Royal Tank

Regiment (RTR). The cavalry retained their traditional

titles, e.g. King’s Dragoon Guards, 1st Northamptonshire

Yeomanry. They also retained the designation regiment

even though they were battalion-sized units. Tank battalions

belonging to the RTR were numbered, e.g. 1st Battalion,

Royal Tank Regiment, usually abbreviated to 1st RTR.

● ● ●

At the

end of the Great War, conventional military opinion held

that the tank, though it had proved useful, would

nevertheless remain an adjunct to the infantry. Existing

tanks were slow, unmaneuverable and mechanically unreliable.

Only a small minority of imaginative military thinkers

envisioned the tank as the decisive weapon on future

battlefields and they were mostly disregarded—the more so as

the conflict just concluded was widely thought to have been “the war

to end war.”

Only in

Britain, the birthplace of the tank, did there exist an

institutional framework for the development of armored

warfare concepts: the Royal Tank Corps (RTC; later the Royal

Tank Regiment) of the British Army. In the beginning, not all

of the “tank prophets” were in agreement as to the tank’s

proper role in a future war. Some, like Colonel J.F.C

Fuller, thought that the tank could function independently

as a “land ironclad”; others believed that the tank should

form part of a mechanized all-arms battle group including

infantry, artillery, engineers, etc. equipped with

specialized armored vehicles of their own. Prominent among

the latter faction was Captain B.H. Liddell Hart, a former

Army officer, invalidated out of the service after being

severely wounded on the first day of the Battle of the

Somme. As a military commentator and journalist with many

contacts in the Army, he was well

placed to spread the gospel of the tank and became its

foremost proponent, far better known than serving RTC

officers such as Fuller, Hobart and Martel, who worked

within the system.

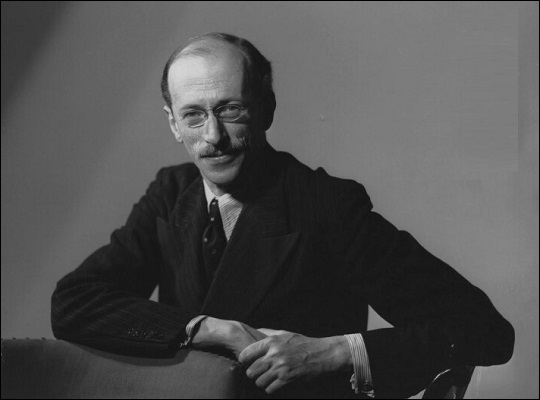

Prophet of armored

warfare: Sir Basil Henry

Liddell Hart (National Portrait Gallery)

Parsimonious peacetime military budgets and the skepticism

of orthodox soldiers limited the RTC’s ability to try out

its ideas, but in 1927 an Experimental Mechanized Force (EMF)

was formed for that purpose. The EMF was a brigade-sized

unit combining light and medium tanks, armored cars,

motorized infantry and engineers, and motor-towed field

artillery. Colonel Fuller was offered the command, but as

the War Office refused to meet his requirements for an expanded

staff, he resigned and went into retirement. The command was

given instead to Brigadier R. J. Collins, an infantry

officer, and in the 1928 Eastland/Westland war game, the EMF

proved its worth. Eastland/Westland and subsequent field

exercises enabled tank tactics to be refined, and drew

attention to many practical requirements of mechanized

warfare: reconnaissance, communications, supply, maintenance. It was

particularly noted that tanks should be equipped with radios

to facilitate tactical control.

A Mark II Medium Tank of

the EMF in 1927 (Imperial War Museum)

In 1928

the EMF was renamed the Armoured Force (AF) and in 1933 a

permanent armored brigade was established. This led to the

formation of the Mobile Division (later the 1st Armoured

Division) in the UK (1937) and the Mobile Force (later the

7th Armoured Division) in Egypt (1938). The commander of the

Mobile Force was Major-General Sir Percy Hobart, the British

Army's leading tank expert, who had previously commanded the

1st Armoured Brigade and served as Inspector of the RTC. But

by this time the British Army, which pioneered armored

warfare concepts in the 1920s and early 1930s, had

surrendered its lead to Germany. This was due partly to

insufficient funding and partly to the innate conservatism

of the British Army.

Major-General Sir Percy

Hobart during World War II (Imperial War Museum)

It was

not that senior officers refused to accept the necessity of

mechanization. They admitted that the Army’s prestigious

cavalry regiments must replace their horses with tanks and

armored cars. What did not change, however, was the cavalry

mind-set. If tanks must replace horses, nevertheless they

would be employed in the traditional cavalry manner:

operating en masse to fight opposing armored

formations, exploit breakthroughs, and pursue retreating

enemy forces. But the infantry support mission was seen in

quite a different light: tanks operating in small groups,

moving at the pace of the infantry, much as tanks had

operated during the Great War. Thanks to this division

of roles and missions, neither the RTC nor the Royal

Armoured Corps, set up in 1939 to administer all armored

units, ever succeeded in evolving a unified mechanized

warfare doctrine.

British

tank design thus proceeded on two tracks. The cavalry would

be equipped with light tanks and “cruiser” tanks, both fast

and lightly armored, the former armed with machine guns, the

latter armed with a 2-pounder (40mm) antitank gun (ATG) plus

machine guns. Tanks for infantry support—“I” tanks as they

were designated—would be relatively slow and well armored,

armed with a 2-pounder ATG plus a machine gun.

Organizationally, the light tank and cruiser tank battalions

would be used to form armored divisions, while the infantry

tank battalions would be used to form tank brigades. Light

tanks would also equip the armored reconnaissance battalions

of infantry divisions and the corps armored reconnaissance

brigades. With a few exceptions, light and cruiser tank

battalions were cavalry units while infantry tank battalions

were part of the Royal Tank Regiment—as the RTC was retitled

in early 1939.

The Mk I (A9) Light

Cruiser Tank (Tank Encyclopedia)

The

British Army’s failure to group all armored units in a

single arm of service, as happened in Germany, had

unfortunate effects on both tank design and tactical

doctrine. The Mk I (A9) cruiser tank, which entered service

in 1939, was certainly fast and its 2-pounder ATG was an

effective weapon, but its armor was altogether inadequate.

The Mk I was followed into service by the Mk II (A10),

originally intended to serve as an infantry tank. Judged

unsuitable for that role, it was reclassified as a “heavy

cruiser tank”—this reflecting its thicker armor and lower

speed compared with the Mk I, now classified as a “light

cruiser tank.” There were close support (CS) versions of

both tanks, armed with a 3.7-inch howitzer in place of the

2-pounder ATG. The CS tank was intended to support other

tanks in action, primary by firing smoke shell to shield

their movements. The light tank was the Mk VI, armed with

one caliber .50 and one caliber .303 machine gun.

The Mk VI Light Tank (Tank

Encyclopedia)

None of

these tanks met the criteria for what nowadays would be

called a main battle tank, i.e. a tank whose firepower,

armor protection and mobility enable it to perform any

mission. But the deficiencies of British tanks were less

important than the faulty tactical doctrine governing their

employment on the battlefield.

Organizationally, the first British armored divisions had

too many tanks and too little infantry. On the eve of war in

1939, the 1st Armoured Division had some 275 light, cruiser

and CS tanks in two light and one heavy armored brigades,

each with three battalions. A support group embodied two

motorized infantry battalions, two field artillery

battalions (motor towed), a motorized engineer battalion and

a battery of 2-pounder ATG (motor towed). The Armoured

Division (Egypt) was incomplete, with only one light and one

heavy armored brigade, a reconnaissance battalion with

wheeled armored cars, a single motorized infantry battalion

and one battery each of field artillery and ATG, both

motor towed. Thus the tanks could count on very little by

way of infantry and artillery support, and combined

arms tactics, integrating the action of tanks, infantry and

artillery, were largely disregarded. But these disadvantages

were not recognized, for it was thought that tanks, massed

in large formations, could fight on their own in the old

cavalry style. War experience, particularly in North Africa,

was to show just how wrong that idea was.

Mk II (A12) Matilda

Infantry Tanks (Imperial War Museum)

As for

the infantry tanks, by 1939 they were grouped in brigades,

each with three battalions, for a total of 151 “I” tanks and

21 light tanks. The first “I” tank was the Mk I (A11)

Matilda, armed with a machine gun only. Its replacement, the

Mk II (A12) Matilda, armed with the 2-pounder ATG and a

machine gun, was just beginning to enter service—only two

had been delivered by September 1939. Though slow, the Mk II

Matilda was the best tank in the British Army’s inventory at

the beginning of World War II. Its armor was impervious to

any antitank gun in service and its gun could

penetrate the armor of any German or Italian tank.

A

shortcoming common to both cruiser tanks and the Mk II

Matilda was that their main armament, the 2-pounder ATG, was

not provided with high-explosive ammunition. If could fire

only solid AT shot, which was useless for any other purpose.

Though perhaps understandable in the case of the cruiser

tanks, this was a strange oversight indeed in a tank

designed to support the infantry.

That

Britain, the birthplace of the tank, failed to capitalize on

the pioneering work of the tank prophets and the EMF is a

sad irony of military history. But the mechanization of the

cavalry, necessary though it was, effectively dissipated the

authority of the RTR, where the tank prophets and their

successors had found their natural home. And the

parochialism inherent in the British Army’s regimental

system compounded the problem. Though the cavalry horse was

retired, the cavalry regiments and the cavalry tradition

survived. Gallantry and dash were honored above close study

and application of tank tactics; the more professional

outlook of the RTR was disregarded if not scorned. But the

maintenance of those cherished cavalry traditions proved

costly, and the bill was to come due in North Africa. Against the

Italians British tanks prevailed, but the advent of Rommel

and his Afrika Korps

exposed the deficiencies of the British Army’s armored

forces in a most painful manner.

● ● ●