● ● ●

It may

well be said that the turning point of the Second World War

was reached on the day that Nazi Germany invaded the USSR:

22 June 1941. At that moment the Grand Alliance (as

Churchill called it) of Britain, America and Russia became

possible, for it seemed only a matter of time before the

United States would enter the war as well. And by December

1941, when the USA did come in, the failure of Germany's

drive to the east was obvious to all. The USSR had not been

defeated in a single blitzkrieg campaign; indeed, it was the

German Army that was fighting for its survival. And the Grand Alliance having become a reality,

faced with its overwhelming power Germany could no longer

hope to win the war.

But

might things have turned out differently? Could Germany have

defeated the USSR in 1941? This question has been debated

since the war ended in 1945. Those who think that a German

victory was never possible offer powerful arguments.

They point out that Germany’s military advantages in 1941

constituted a wasting asset, bound to dwindle and disappear, while the USSR’s military

potential was enormous, particularly in

alliance with the UK and the USA. Those who think that a

German victory was possible tend to point the finger of

blame at Hitler, whose meddling, they assert, threw away

Germany’s one chance to knock out the USSR.

Whether

Nazi Germany could have defeated the USSR at all is

a doubtful question, whoever was commanding the former’s

armies. If we assume, however, that the Army High Command (Oberkommando

des Heeres or OKH)

had been given free reign to conduct Operation Barbarossa as

it saw fit, the 1941 campaign may well have been brought to

a successful conclusion with the capture of Moscow. This was

the objective of the preliminary invasion plan, code-named

Otto, known informally as the Marcks Plan after its

principal author, that was drawn up by the OKH in 1940. As

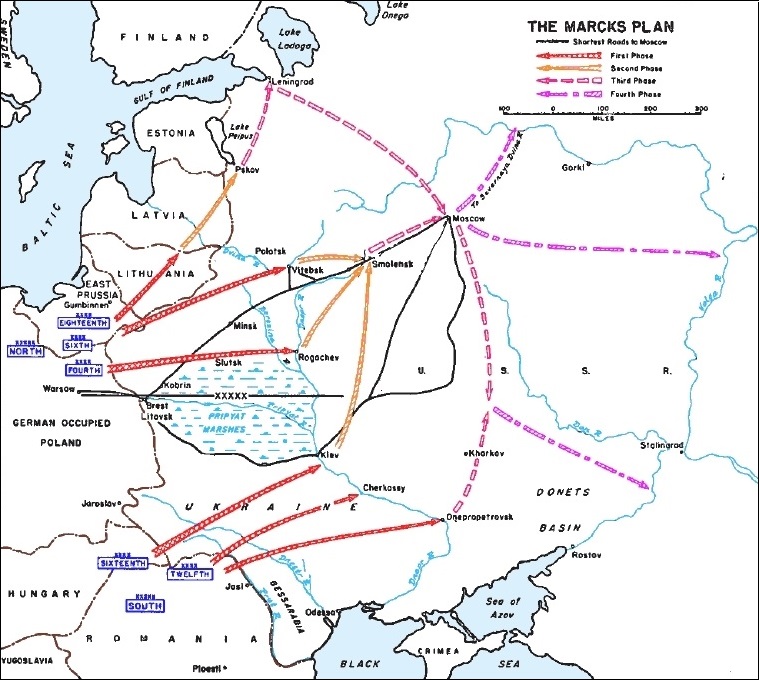

the map shows, it envisioned an operation in four phases,

defeating the Red Army in the western USSR, capturing

first Leningrad, then

Moscow, and

finally advancing to the

A-A

(Arkhangelsk–Astrakhan) line, bringing most of European

Russia under German occupation. Two army groups would carry

out the offensive, one north and one south of the Pripyat Marshes.

But Hitler was dissatisfied with the Marcks Plan and in his

Directive 21 for the invasion of the USSR he amended it to

provide three army groups, two of them making the main

effort north of the Pripyat Marches with Leningrad and

Moscow as simultaneous primary objectives. As a necessary

preliminary, the Red Army formations standing in the western

USSR would be encircled and destroyed before they could

withdraw to the east. The A-A line remained

the ultimate, albeit vaguely defined, objective. This

revised plan was given the code name

Barbarossa.

Operation Otto, the preliminary OKH plan

for the invasion of the USSR (Department of History, USMA

West Point)

Operation Barbarossa commenced on 22 June 1941, and the Red

Army forces in the western USSR were soon routed, suffering

astronomical losses in both men and material. But neither Leningrad nor Moscow were captured and by late

July OKH realized that it had seriously underestimated the

strength of the Red Army. For every division destroyed, a

new one appeared in the enemy’s order of battle. It was true

that many of these divisions were hastily organized and

poorly trained. Some were formed with personnel drawn from

the various branches of the NVKD; others consisted of

“workers’ militia” units. Many lacked artillery, antitank

guns—even mortars and machine guns. And Soviet troops

who'd been bypassed or encircled continued to resist tenaciously, posing a

worrisome threat to the Germans' vulnerable flanks and lines

of communication. It was clear that

the Red Army, if down, was not out.

As for the German armies, heavier-than-anticipated casualties

and

growing supply problems were beginning to make their effects

felt. The

all-important mobile forces especially—the panzer and motorized

infantry divisions—were in urgent need of rest and

refitting. An operational pause was clearly necessary so

that the armies could be resupplied and

reinforced before resuming the offensive. It was during this

lull that the strategic dispute between Hitler and the OKH

played itself out.

Brauchitsch, the Commander-in Chief of the Army, Halder,

the Chief of the OKH, Bock, commanding Army Group Center, and Guderian, commanding Second Panzer Group, believed that an attack on the Moscow

axis would compel the enemy to stand and fight, resulting

in a decisive battle that would destroy the main body of the Red

Army and end with the capture of the Soviet capital. But Hitler disagreed: He desired to

capture Leningrad, then switch the main

effort to the southern sector of the front. The Führer

believed that capturing the economic resources of

the Ukraine would irretrievably cripple the USSR, adding

that those resources were essential to the long-term

German war effort. He also insisted that it was necessary

both to eliminate the surrounded enemy forces behind the

German front line and to

destroy the still-formidable Red Army forces facing Army

Group South in the Ukraine. He was deaf to OKH’s argument that

victory on the Moscow axis would secure those objectives

in any case.

Needless

to say, the Führer's opinion prevailed: Army Group North was

instructed to resume its advance on Leningrad, and in late August

the main effort was switched from the central to the

southern sector of the front. Though the Leningrad offensive

soon stalled, the Germans scored a

resounding victory in the Ukraine. Hitherto the Red Army in that

region had put up a stout fight against Army Group

South, maintaining its cohesion despite losing ground. But the intervention of Guderian’s

Second Panzer

Group, descending upon the enemy's rear in the Kiev

area, caused the defense to collapse.

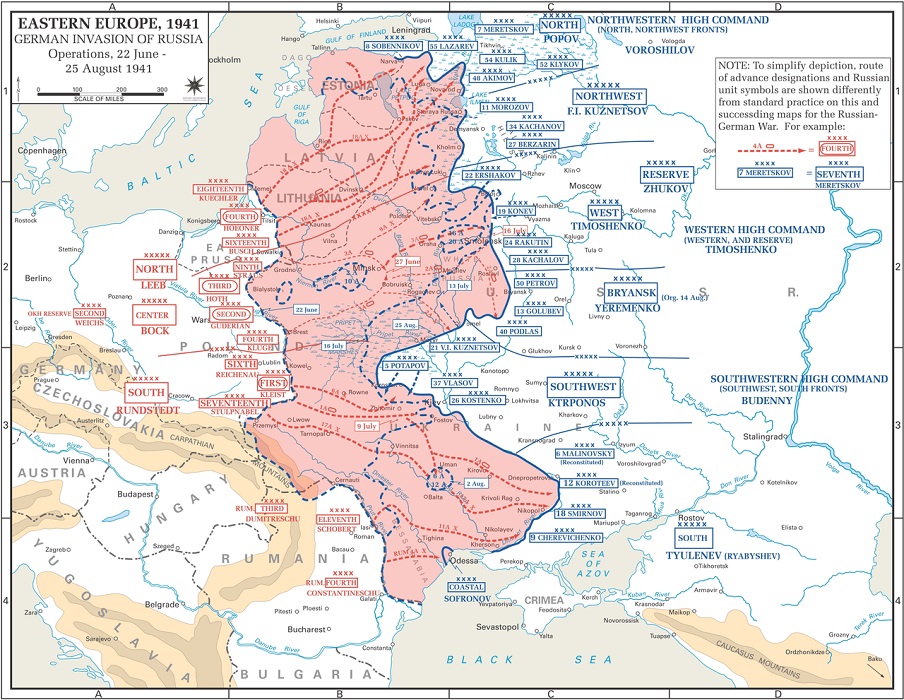

Operation Barbarossa: Initial German

deployments and first phase (Department of History, USMA

West Point)

The

First Battle of Kiev, which ended in the third week of

September cost the Red Army more than 600,000

casualties. But this German success, though impressive,

was not decisive. Thanks to the lateness of the season, for

the Germans there were no vital objectives within

reach east of Kiev. The Russians, however, could still trade space for

time, and with mobilization reaching full flood and

reinforcements coming in from the eastern USSR, they could

still replace their losses. The German main

effort was therefore switched back to the Moscow axis, the

drive on the capital resuming on 30 September—unsuccessfully, as

things turned out.

However,

had the advance to Moscow been resumed in late August, after

the German armies in that sector had been rested, reinforced

and resupplied, things could have turned out very

differently. At that date Red Army forces on the Moscow

front were still in shaky condition and a timely attack by

Army Group Center might well have smashed them. And in

that case what might have happened? First, it would probably have led

to the fall of both Moscow and Leningrad. The Soviet capital was the

nexus of rail and road communications in central and northern Russia. Its

capture by the Germans would have isolated the Leningrad

region, leading to a more or less automatic collapse of the

Red Army in that sector. Second, the fall of Moscow and a

further eastward advance by the Germans toward Gorki would

have menaced the northern flank of Soviet forces in the Ukraine, compelling them to retreat eastward, possibly as far as the

Volga.

Still,

in strictly military terms even so gigantic German victory

would not necessarily have finished off the USSR. But as

Clausewitz noted, war is the continuation of politics by

other means, so the political consequences of Moscow’s fall

must also be considered.

In that

connection it should be noted that Stalin himself harbored

grave doubts about the USSR’s staying power in a war against

Germany. He realized better than anyone that such spectacles

as the Five-Year Plan and military parades in Red Square

concealed potentially fatal fragilities. The deprivations of

the 1930s—crash industrialization, the collectivization of

agriculture, the Great Purge—had levied a hideous toll of

death and suffering on the Soviet peoples. Stalin knew that he and his regime were widely hated; he had

good reason to fear that in the event of a German invasion,

the people might turn on the Party. Moreover, he knew that

thanks to his purge of its officer corps, the Red Army was

quite unprepared for war. Stalin believed that at all

costs, war with Germany, however inevitable in the long

term, had to be delayed for as long as possible. That was why the Soviet leader

took such pains to maintain good relations with Germany

between 1939 and 1941, and why he was deaf to credible

intelligence concerning Hitler’s real intentions.

So if

Moscow had fallen in the summer of 1941, the political

fallout might have secured victory for Germany. After presiding

over such a catastrophic defeat, it's plausible to think

that the Soviet regime would have collapsed, perhaps with a

cabal of generals putting Stalin and his cronies in front of

a firing squad. Or if Stalin managed to weather the debacle

he might have thrown up the sponge, accepting harsh peace

terms as the price of survival, with the option of renewing

the fight another day. Who can say? Certainly a case can be

made for the German capture of Moscow in late August-early

September of 1941—but that, had it

happened, would have cleared the way for a near-infinity of

alternate histories.

● ● ●