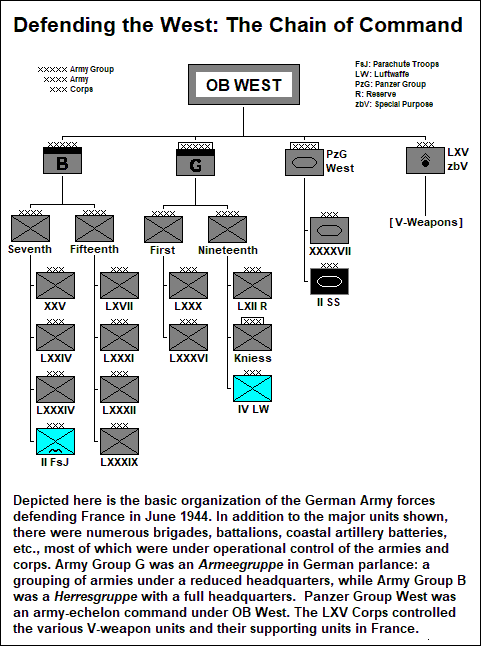

The German forces tasked to

repulse the long-expected Allied invasion of France were

under the command of the Oberbefehlshaber

West

(Commander-in-Chief West)—OB

West for short—which also referred to the headquarters as a

whole. Since March 1942

this command had been held by Field Marshal Gerd von

Rundstedt, the Army’s senior officer,

who

in June 1944 was sixty-nine years old. OB West

had two major formations:

Armeegruppe

G

(Colonel-General

Johannes Blaskowitz), responsible for the defense of the

Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts of France; and

Heeresgruppe

B (Field Marshal Erwin Rommel),

responsible for the defense of Brittany and the Channel

coast of France and Belgium. An additional headquarters,

Panzergruppe West

(later to become

5. Panzerarmee), controlled three

of the six panzer divisions in the

HG B zone.

OB West was answerable to the High Command of the Armed

Forces: Oberkommando der Wehrmacht

or OKW. In

his capacity as supreme commander of the armed forces Hitler

issued his orders through OKW, which also served as his

planning staff. (The High Command of the Army,

Oberkommando des Heeres

or OKH, was by now restricted to the conduct of operations

on the Eastern Front on Hitler’s behalf in his capacity as

commander-in-chief of the Army.)

If this

chain of command seems straightforward, the reality was

otherwise. As Rundstedt complained, his authority was

circumscribed by Hitler, who was not hesitant to issue

orders over the head of OB West. Moreover, neither Rundstedt

nor Rommel had full control of the six panzer divisions in

the

HG B

zone. The three under

Panzergruppe West

were designated as OKW reserves—meaning that they could not

be committed to action without Hitler’s express

authorization. This was to have fateful consequences on the

day of the invasion.

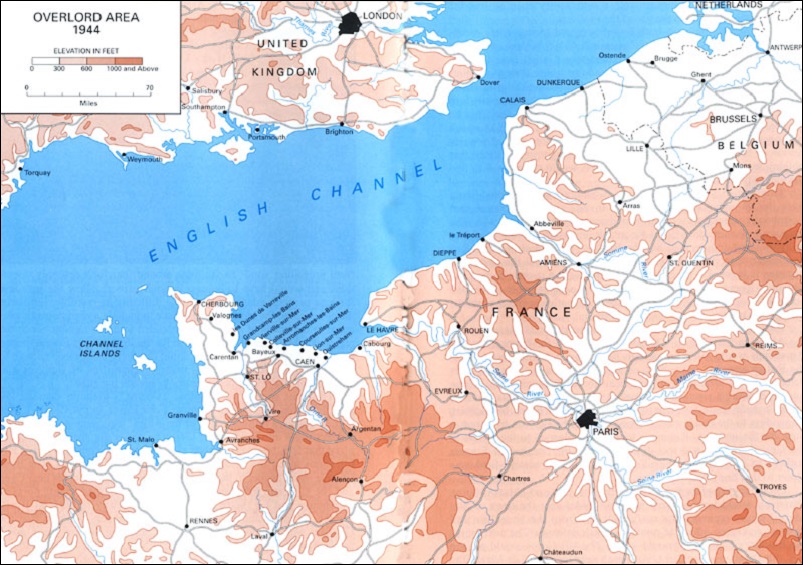

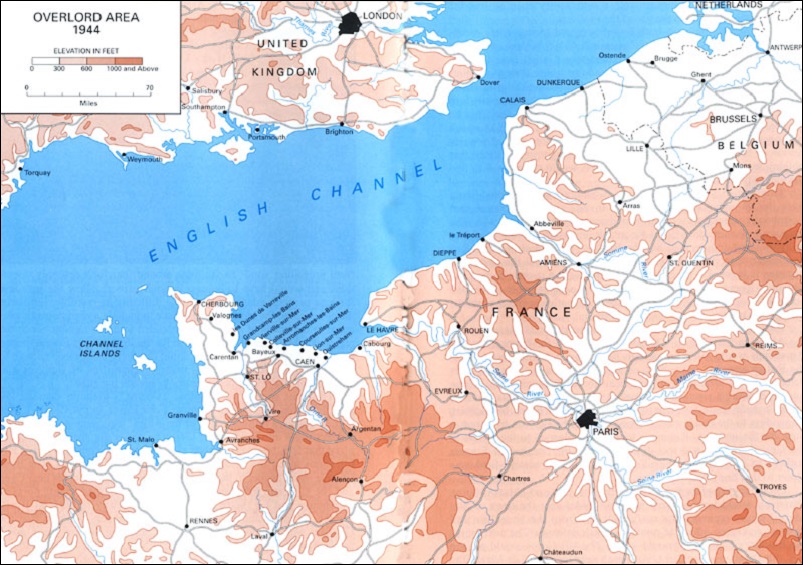

Normandy and northwestern

France (Department of History, USMA West Point)

Since it

was considered certain that the invasion, when it came,

would strike somewhere between Brittany and Calais,

two-thirds of the forces at the disposal of OB West were

allotted to

HG B. The question was precisely where

in this area the Allies would land. The obvious spot was the

Pas de Calais, where the English Channel was at its

narrowest. But there were reasons to think that the enemy

might choose Normandy instead. The early seizure of a major

port was an obvious Allied objective and Cherbourg at the

tip of the Normandy peninsula fitted the bill. And this

indeed was a major consideration in the Allies’ choice of

Normandy. Hitler himself, though he agreed with his generals

that the Pas de Calais was the Allies' most likely target,

could not rid himself of the suspicion that they might

strike in Normandy instead—one more example of the intuition

that the Führer sometimes

displayed during the war.

Two

additional factors complicated this guessing game. First,

there was Hitler’s anxiety concerning Norway, where he

suspected that the Allies might attempt a landing with the

objective of barring Germany’s access to Swedish iron

ore—essential to industrial production. Second, there was

Operation Fortitude, an Allied deception plan designed to

convince the Germans that the invasion would come at the Pas

de Calais. This involved the creation of a phantom army

group in England, supposedly under the command of Lieutenant

General George S. Patton. Fake radio traffic, dummy tanks

and guns made of wood and canvas and other deceptions were

highly successful in convincing German commanders that Pas

De Calais was the Allied target. Even on and after 6 June

1944, Rundstedt and others suspected that the Normandy

landing was merely a diversion, and that the real invasion

had yet to be launched.

Nor was

there unanimity of opinion regarding operational and

tactical matters. Rommel, whose task it would be to conduct

the defensive battle, believed that it was vital to

concentrate all reserves close to the coast, in readiness to

meet the invasion on the beaches and throw it back into the

sea. If the Allies were not promptly repulsed, he argued,

they were unlikely to be driven out at all. Rommel’s

experiences during the campaign in North Africa had

convinced him that thanks to Allied air superiority,

reserves positioned inland would be unable to reach the

coast in time to prevent the enemy from consolidating a

bridgehead.

Rommel (left) on

an inspection tour of the Channel coast defenses (World War

Photos)

But his

superior Rundstedt and many others on the OB West staff

disagreed. Basing themselves on traditional military

principles of concentration and mass, they advocated the

creation of a powerful panzer reserve, positioned well

inland, to deliver a well-planned, carefully prepared

counterattack, smashing the invaders in their beachheads

before they could build up their strength. The preparation

and conduct of this counterattack was to be the mission of

Panzergruppe West; in the meantime the German infantry

divisions, withdrawn out of range of naval gunfire, would

dig in and cordon off the invasion zone.

Both

sides appealed to Hitler—who characteristically split the

difference. Three of the six immediately available panzer

divisions were placed under

HG B. The other three

remained with

Panzergruppe West and were not to be committed

to action without OKW approval. In effect, the Führer’s

decision approved Rommel’s plan without giving him the

forces necessary to do the job. The beaches were sown with

mines, strewn with obstacles and covered by artillery.

Protected fighting positions for the defending infantry were

constructed with interlocking fields of fire. But the

reserves—the panzer divisions especially—were not positioned

as Rommel desired. On D-Day only one of them, the

21.

Panzer-Division, was immediately available to launch a

counterattack—which failed. And just as the Desert Fox had

predicted, the enemy was able to consolidate a bridgehead

from which he could not be dislodged.

Whether

Rommel or Rundstedt was right in this dispute over

operations and tactics is a doubtful question, though with

hindsight it appears that Rommel’s assessment of the

situation was more realistic. In view of the Allies’ overall

superiority of forces it seems unlikely, albeit it not quite

impossible, that the Germans could have repulsed the

invasion. But there can be no doubt that Hitler’s failure to

make a clear-cut decision was prominent among those factors

contributing toward the German Army’s catastrophic defeat in

the Battle of Normandy.

● ● ●