|

● ● ●

After the end of the Great War, Germany was

compelled by the victorious Allies rapidly to demobilize its

Army. On 11 November

1918 it numbered well over 4 million men; a year later it was down

to 300,000. Under the terms of the Armistice vast quantities of

munitions, weapons and aircraft had to be handed over to the

victorious Allies, and it soon became obvious that they intended for

Germany to be substantially disarmed.

The 1919 Treaty of Versailles

formalized this intention. The Treaty stipulated that the German

Army of the Weimar Republic should consist of no more than 100,000 men: 4,000 officers and

86,000 other ranks. All were to be long-service professional

soldiers; conscription and short service were banned so as to

prevent the buildup of a trained military reserve. The Großgeneralstab (Great General Staff) and the

Kriegsakademie

(War Academy), the traditional intellectual centers of the German

Army, were abolished. As for weapons, the Peace Treaty permitted

Germany to keep no more than 105 armored cars, 204 77mm field guns,

84 105mm light field howitzers, 252 mortars, some 2,000 machine guns

and about 100,000 rifles and carbines—barely enough to arm the

Army’s seven infantry and

three cavalry divisions. Heavy artillery, tanks, frontier

fortifications and military aircraft were all prohibited. In this

form the new German Army, called the Reichswehr, was

organized in 1920 and officially established in January 1921.

Command Flag of Reichwehr-Gruppenkommando 1 (Berlin)

But from the day of its founding the

Reichswehr—it

must be said with the connivance of the German government—employed

every possible subterfuge to evade the disarmament provisions of the

Peace Treaty. The actual military budget was always higher than officially admitted: twice as high between 1924 and

1928. This enabled the

Reichswehr

to acquire and stockpile three times as many rifles and six times as

many machine guns as were permitted to it by the terms of the

Versailles Treaty, along with substantial

additional quantities of mortars, field guns and field howitzers.

The German Transport Ministry subsidized clandestine military

aircraft development and aircrew training, while German industrial firms like Krupp carried

out covert research and

development work on tanks and heavy artillery

The

Treaty's manpower restrictions were also circumvented in various ways.

Many officers and soldiers who could not be employed on military

duties went into the

Grenzshutzpolizei

(Border Police) and the police forces of the German federal states,

which were organized along paramilitary lines. There was

also the so-called Black

Reichswehr:

frankly illegal military formations maintained under a variety of

cover designations, e.g. the “labor battalions” comprising some

18,000 men that were set up in Prussia under

Reichswehr

auspices. Many of their men came from the

Freikorps, the unofficial

volunteer military units that had sprung up in 1918-19 to defend

Germany’s eastern borders against Polish encroachment. The

Freikorps consisted mostly

of Great War veterans and came to play a major role in radical

right-wing politics, the most notorious example being the

participation of

Marinebrigade Ehrhardt

in the unsuccessful 1920

Kapp Putsch. Nonetheless, the Reichswehr

looked upon the

Freikorps

as a de facto military reserve and supported them with

arms and training.

By these means a modest increase in the size of the

Reichswehr

could be accomplished in the event of an emergency.

Men of the Prussian State Police in Berlin, 1929.

(Bundesarchiv)

Diplomacy also played an important role in clandestine rearmament.

In April 1922 Germany and the USSR concluded the Treaty of Rapallo, and

subsequently the

Reichswehr

set up a number of secret testing and training facilities in the

Soviet Union. These included a tank training establishment at Kazan

and an air force training base at Lipetsk. German industrial firms

also set up shop in the Soviet Union, where military R&D work could

be conducted far from prying eyes. In return for providing these

facilities, the USSR gained access to German military

technology. Farther afield, Gustav Stresemann, who served as Foreign

Secretary and Chancellor and between 1923 and 1929, worked

assiduously to establish contacts in countries including Sweden and

the Netherlands, where work on banned weapons could be carried out.

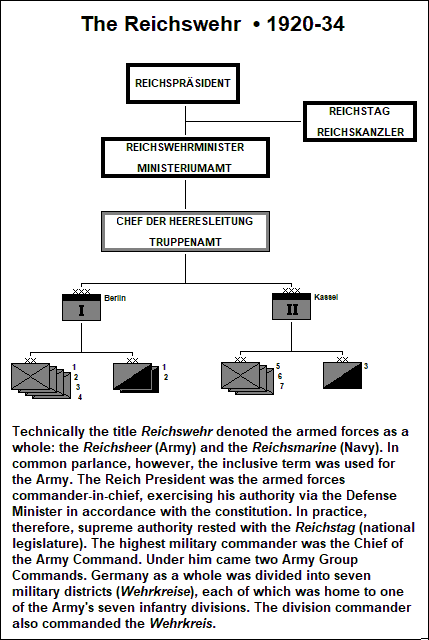

The effective commander of the

Reichwehr

was the Chef der Heeresleitung (Chief of the Army

Command). The first man to hold this title was General Hans von

Seeckt, a Prussian aristocrat and General Staff officer who’d made

his name on the Eastern Front during the Great War. After the

November 1918 armistice he was appointed to the committee charged

with the organization of the Weimar Republic’s peacetime army, and

it was he who gave the Reichswehr its final form.

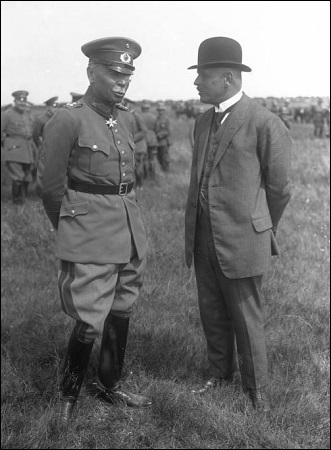

General Hans von Seeckt and Defense Minister Otto

Gessler in conversation during the 1925 maneuvers (Bundesarchiv)

From the beginning Seeckt

regarded the Reichswehr as a basis for a

major military

buildup when the time came, as almost all Germans

hoped it would, for the shackles of the Treaty of Versailles to be

struck off. To that end he ensured that only the best officers

and men were selected for the 100,000-man army. And though the

Great

General Staff was no more, its spirit lived on in the

Truppenamt

(Troops Office), which performed the staff functions essential to

any military force. Seeckt was also determined to keep the Army

clear of politics. Like many officers his outlook was authoritarian

and he merely tolerated the Weimar Republic. He laid down that the

Army was the guardian of the German nation in the most general

sense, not the servant of any particular regime or constitution.

Seeckt believed that the

restoration of German power depended on the establishment and

maintenance of good relations with Russia. Unlike most other

German conservatives, he had no fear of Bolshevism. Predictions of

the Red Army's arrival on the Elbe or even the Rhine he dismissed as

"fairy tales to frighten little children." His 1922 memorandum to

Count Ulrich von

Brockdorff-Rantzau, a former foreign minister who had just been

appointed Ambassador to the Soviet Union, was remarkably prescient:

With Poland we come now to the

core of the Eastern problem. The existence of Poland is

intolerable and incompatible with Germany's vital

interests. She must disappear and will do so through her

own inner weakness and through Russia — with our help.

Poland is more intolerable for Russia than for

ourselves; Russia can never tolerate Poland. With Poland's

collapse one of the strongest pillars of the Peace of

Versailles, France's advance post of power, is lost. The

attainment of this objective must be one of the firmest

guiding principles of German policy, as it is capable of

achievement—but only through Russia or with her help.

Poland can never offer Germany any

advantage, either economically, because she is incapable

of development, or politically, because she is a vassal

state of France. The restoration of the frontier between

Russia and Germany is a necessary condition before both

sides can become strong. The 1914 frontier between

Russia and Germany should be the basis of any

understanding between the two countries...

Here was prefigured the policy

that Hitler would follow from 1939 to 1941—which in the short term

did indeed produce the situation that Seeckt envisioned.

Ironically, a minor political misstep compelled Seeckt to retire in

1926, but by then his stamp had deeply impressed itself on the

Reichswehr.

His practical work provided a basis for rapid expansion when

Hitler embarked upon his rearmament program—and the

aloofness from politics that he had nurtured among the officer corps was to have parlous

consequences for both the Army and the nation it served.

● ● ●

|