|

● ● ●

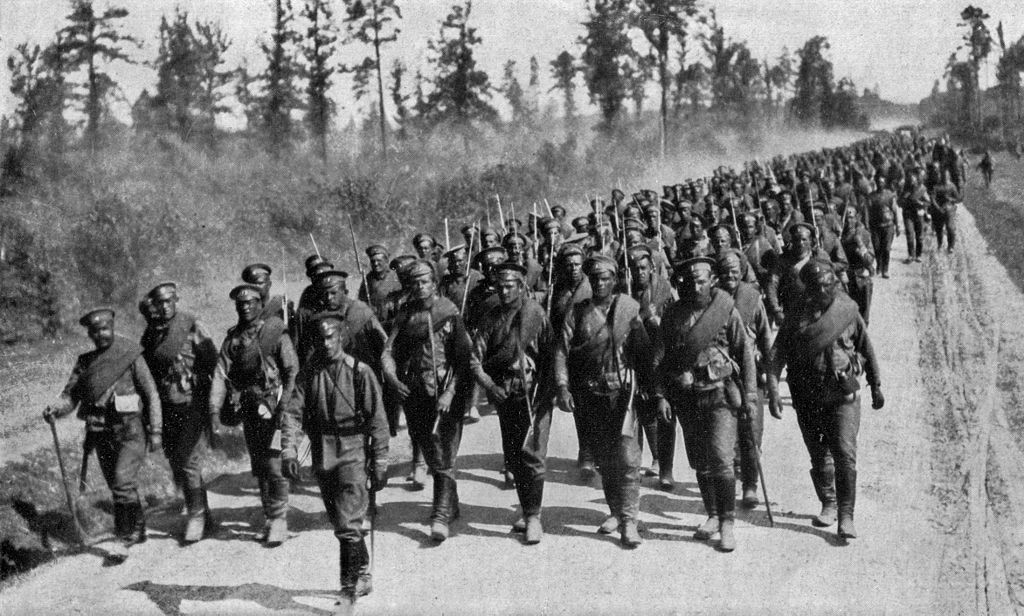

In August 1914 the Russian Army mobilized well

over three million men in 115 infantry divisions, 24 cavalry

divisions, 17 rifle brigades and 8 cavalry brigades—a force that was

to grow substantially as reservists were recalled to the colors and

new units were raised.

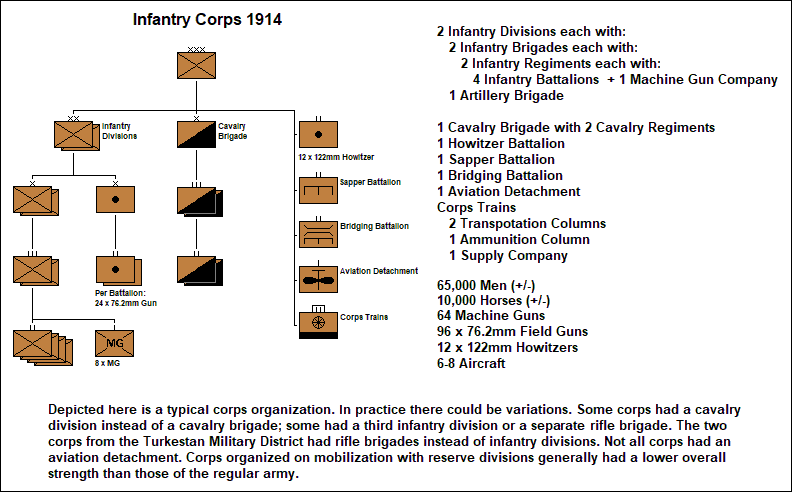

The Army's basic combat formation was the

army corps, usually consisting of two infantry divisions, a

cavalry division or brigade, an artillery howitzer battalion, a

sapper battalion, a bridging battalion, a supply battalion and an

aviation detachment. The infantry division consisted of a

headquarters company, two infantry brigades and an artillery

brigade. Each infantry brigade controlled two infantry regiments;

the artillery brigade had two battalions, each with three batteries

of field guns. By modern standards the infantry division's support

services were minimal. On campaign a company of the corps sapper

battalion and perhaps a squadron of cavalry were detached to each

infantry division, but supply and communications troops were

controlled by the corps and field army headquarters. Cavalry

divisions had a similar organization—two cavalry brigades each with

two cavalry regiments—but instead of an artillery brigade they had

only one battalion of horse artillery.

A field army—nine were constituted upon

mobilization—consisted of three to five army corps plus heavy

artillery, engineer, supply, transport and aviation units. The

senior field headquarters was the front (army group), controlling a

variable number of armies. During the war the principal fronts were

Northwest Front (against Germany) Southwest Front (against

Austria-Hungary) and Caucasus Front (against Turkey).

Command Flag of the XI Army Corps (Graphic by Tom

Gregg)

Contrary to legend, the Russian Army in 1914

was reasonably well equipped with small arms (including eight

machine guns per infantry regiment) and field artillery. The standard

76.2mm field gun was an excellent weapon of its type and each

infantry division had 48 of them. But the lack of light and medium

field howitzers capable of high-angle fire was a serious deficiency.

The infantry divisions had none and most army corps had only one

artillery howitzer battalion with twelve 122mm howitzers. Heavy

artillery suitable for use in the field was also in short supply;

only a few corps had a heavy artillery battalion with 152mm

howitzers and 107mm long-range guns. Against the Austro-Hungarian

Army, which had a similar artillery deficit, this did not matter

very much, but against the better-prepared German Army it was to

prove a major handicap.

More serious still was the ammunition

situation. Prewar planning had greatly underestimated the rate at

which ammunition—artillery ammunition in particular—would be

expended in battle. Existing stocks were quickly consumed in the

1914 campaign and new production was unable to keep up with demand.

Most ammunition was manufactured in state-owned factories and there

had been no serious planning for the conversion of civilian industry

to war production. Consequently the Russian Army suffered a chronic

shortage of ammunition. Production of rifles, machine guns and

artillery was also insufficient to both replace losses and arm newly

raised divisions. These problems were gradually solved, but by the

time they were the Russian Army had already suffered crippling

losses and the country was moving toward revolution.

The shell shortage, as it came to be called, did prove useful in

one respect, serving Russian commanders as a convenient alibi for

defeat. After each disaster the cry went up for ever more guns and

shells—enough to pulverize the enemy's defenses. And the failure to

provide munitions in the quantities demanded enabled the generals to

shift the responsibility onto the government. In fact, however, the

shortage of weapons and munitions, though real enough, was never so

serious that it could not have been compensated for by careful

planning and appropriate tactics. But this, unfortunately, was

easier said than done.

For another problem that bedeviled the Russian

Army was a shortage of trained staff officers, noncommissioned

officers and technical troops. Most conscripts and reservists were

illiterate peasants: hardy, obedient, patriotic and brave but

difficult to train in any but the most rudimentary military duties.

It was particularly hard to find sufficient men for those service

branches requiring formal education and technical qualifications,

such as the artillery, engineers, signal corps, railway troops, air

service, etc. And in sharp contrast to the well-educated,

well-trained noncommissioned officer corps of the German Army,

Russian NCOs were usually not much better educated than the men they

led. As a result, crude battlefield tactics exacerbated by poor

staff work regularly turned defeats into debacles. The field

artillery, which considered itself the elite branch of the service,

was disdainful of the infantry—"cattle" in the opinion of artillery

officers—and coordination between them was generally poor. In

many cases the artillerymen simply pulled out of action when things

began to go wrong, saving their guns but leaving the infantry in the

lurch.

A Russian howitzer battery in action

(Imperial

War Museum)

This shortage of trained and qualified

personnel also set limits on the wartime expansion of the army.

Peasant manpower was available in plenty, but it was exceedingly

difficult to find the necessary officers and technical specialists

to make newly raised reserve divisions effective. The mid-war

shortage of weapons and ammunition only compounded the problem. In

combat against the Germans, these poorly trained units tended to

fare badly, falling to pieces or simply evaporating in the face of a

coordinated attack.

All these factors conspired to limit the

Army's combat effectiveness. Against the Austrians and Turks the

Russian Army proved more than capable of holding its own, but

against the Germans its deficiencies resulted in a succession of

costly and demoralizing defeats.

Further exacerbating the Russian Army’s

problems was the confusion of Stavka, the high command. In peacetime

there had been no overall army headquarters. Upon mobilization

Stavka was hastily botched together and in the opening round it

failed to exert firm control over the field armies. The primary

culprit was factionalism. The Army’s senior officers were split

between two groups: the “Northerners” who believed that the Army

should make its main effort against Germany, seen as the main enemy,

and the “Southerners” who favored making the main effort against

Austria-Hungary, seen as easier to defeat. In hindsight it appears

that the Southerners had the better argument: Austria-Hungary's

defeat would fatally have undermined Germany's position. But nothing

was done to implement this strategy nor, indeed, to develop any sort

of overall strategy.

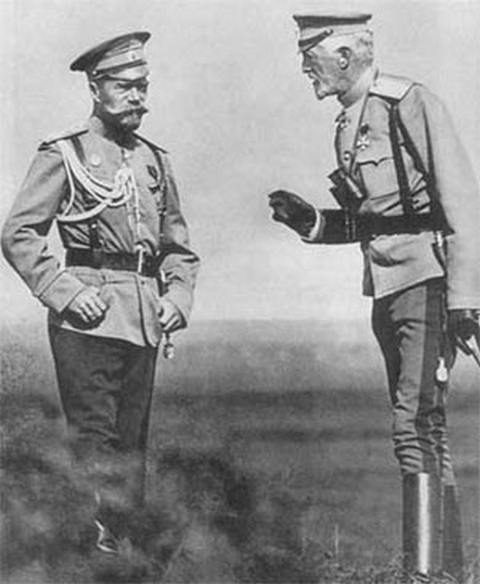

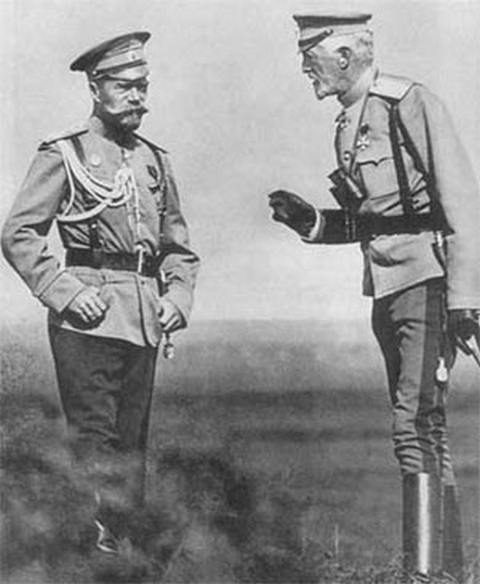

Tsar Nicholas II (left) and his uncle, Grand Duke Nicholas

(Imperial War Museum)

The commander-in-chief, Grand Duke

Nicholas—the Tsar’s uncle—was a much-admired figure but even his

prestige in the Army was ineffective in resolving this dispute over

strategy. So the Russian Army found itself fighting what were

virtually two separate

wars against Germany and Austria-Hungary, to the accompaniment of

much wrangling over the allocation of reserves, replacements and

supplies. The two army groups—Northwest Front against Germany and

Southwest Front against Austria-Hungary—seldom coordinated their

action and Stavka, which was supposed to enforce such coordination,

was largely ignored. Thus victories over the Austrians in 1914 and

1916 could not be fully exploited: Northwest Front proved reluctant

to part with reserves for the benefit of its rival, Southwest Front.

But the string of defeats it suffered at the hands of the Germans,

culminating in the loss of the Polish salient, essentially paralyzed

Northwest Front. Controlling the larger part of the forces on the

Eastern Front, it did nothing—and its paralysis proved fatal for

Russia.

Whether a properly coordinated strategy,

defensive against Germany, offensive against Austria-Hungary, would

have produced better results for Russia is an interesting but

doubtful question. Of all the major belligerents, tsarist Russia was the

one most susceptible to civil unrest and revolutionary turmoil under

the shock and stress of war. What is certain is that the

non-strategy actually pursued invited needless defeats while

throwing away hard-won victories, driving the country toward

breakdown and revolution. So perhaps, just perhaps, a coherent

strategy, imposed by an effective high command, might have staved

off disaster. But given Russian realities in 1914, it’s difficult to

see where such a strategy and such a high command could have come

from.

● ● ●

|