The following abbreviations are

used in this article: AA (antiaircraft), DD (destroyer), DE

(destroyer escort), DP (dual-purpose surface/AA gun), RN

(Royal Navy), USN (United States Navy). The F4F Wildcat

fighter was designed and originally produced by Grumman.

When that company switched to production of the follow-on

F6F Hellcat, responsibility for Wildcat production passed to

General Motors, and the Wildcats it produced were designated

FM. Similarly, when TBF Avenger torpedo bomber production

passed from Grumman to General Motors, the aircraft’s

designation became TBM. To avoid confusion, the designations

F4F and TBF are used throughout this article. The air group

operating from escort carriers was designated as a Composite

Squadron (VC), e.g. VC-10, assigned to USS Gambier Bay

(CVE 73). The USN

initially classified the jeep carriers as auxiliary

aircraft escort vessels (AVG). In early 1942 they were

reclassified as auxiliary aircraft carriers (ACV), and in

mid-1943 they became escort aircraft carriers (CVE). Again

to avoid confusion, the CVE classification is used

throughout this article.

● ● ●

During World War II, the US Navy

operated three categories of aircraft carriers: fleet

carriers (CV), light fleet carriers (CVL) and escort

aircraft carriers (CVE). The CVs and CVLs were strike

carriers designed for offensive operations. CVEs—the jeep

carriers as they were nicknamed—were either conversions of

civilian merchant ships or new construction based on

mercantile designs. As such they were significantly smaller

and slower than the CVs and CVLs.

The CVE’s origins may be traced to

World War I, when various merchant vessels were taken into

naval service for conversion to seaplane carriers. The

primary user was Britain’s Royal Navy, which commissioned

around a dozen such ships. A typical example was HMS

Empress, a

former cross-Channel steamer that could carry six seaplanes.

Most of these ships had no flight deck, the aircraft being

handled by cranes. They proved useful, however, and in the

1930s the Admiralty had plans to requisition five passenger

liners for conversion into auxiliary carriers for service as

convoy escorts, training ships and aircraft transports.

Nothing was done, however, since at the time the Royal Navy

possessed insufficient aircraft to provide even its fleet

carriers with full air groups.

Only with the onset of World War II

did Britain embark upon an auxiliary carrier program. A

number of merchant ships were requisitioned and converted,

the first of which was HMS Audacity, formerly the

German cargo liner Hannover, which had been captured

in March 1940. Audacity had a full-length flight deck

but no island, catapult or internal hanger, her eight

aircraft being carried on deck. Despite these unsatisfactory

features she operated successfully in the Atlantic,

providing effective air cover for convoys between the UK and

Gibraltar, until she was torpedoed and sunk by a U-boat in

December 1941.

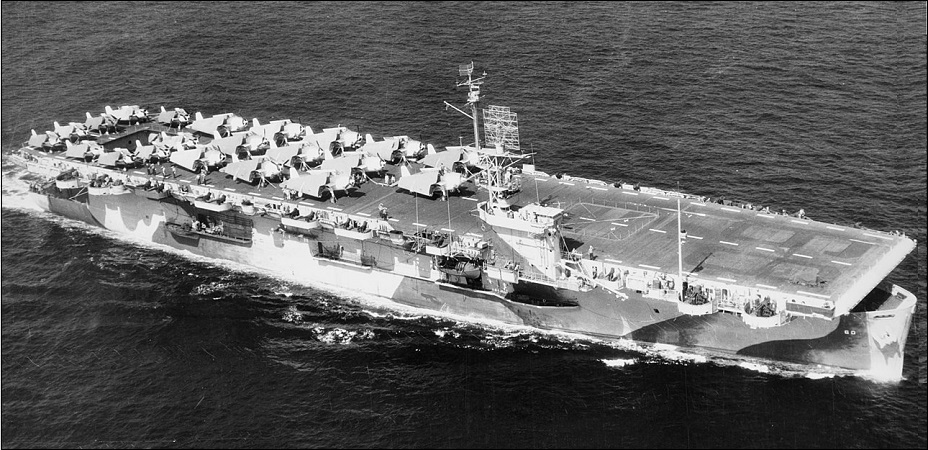

The first of the

jeep carriers, USS Long Island (CVE-1),

seen here serving as an aircraft transport in

1944. On deck are 21

F6F Hellcat

fighters,

20 SBD Dauntless dive

bombers and two Grumman J2F Duck

utility floatplanes.

(Wikimedia Commons)

At first the CVE concept was looked

upon with disfavor by the USN, which preferred large fleet

carriers. But the need for additional carriers in 1942 led

first to the development of the so-called light fleet

carriers built on cruiser hulls and then to a series of

small auxiliary carriers, the first of which was USS Long

Island, formerly the cargo ship Mormacmail.

She was acquired by the Navy and converted in 1941. The

initial intention was to employ her as an aircraft

transport. After completion, however, she received an air

group and embarked upon a series of trials to test the

concept of the escort aircraft carrier. Long

Island was soon joined

by a sister ship, USS Charger,

which had originally been earmarked for transfer to the RN.

These two ships were the prototypes for the mass-produced

“Bogue” class CVEs, 45 of which were built from 1942 to

1944.

The first 22 units of the “Bogue” class were conversions of

completed or near-complete US Maritime Commission Type C-3

cargo ships; the remaining 23 were built as carriers from

the keel up. Long Island

and Charger

were diesel propelled with a maximum speed of about sixteen

knots, which was considered too slow. The “Bogues,”

therefore, were given steam turbine propulsion, raising

their maximum speed to 18-19 knots. Their full-load

displacement was 14,200 tons, overall length was 495 feet,

waterline beam was 65 feet, and flight deck length was 440

feet. The internal hanger was served by two flight deck

elevators and the ships were fitted with a single aircraft

catapult. Experience with the flush-decked Long

Island showed the need

for an island bridge and flight control position. Thus

Charger was

completed with a small starboard-side island and a similar

one was adopted for the “Bogues”

As completed they were armed with a pair of 5in/51 guns plus

ten single 20mm guns as light AA.

USS Breton

(CVE-23) of the "Bogue" class, shortly after

commissioning on 9 April 1943. Visible on her flight

deck are the two elevators serving the internal

aircraft hangers. Also visible under the flight deck

aft is one of the two 5in/51 guns with which the "Bogues"

were originally armed. They could not be used

against aircraft and were replaced by a single

5in/38 DP gun right aft. (National Museum of Naval

Aviation)

Of the 45

“Bouge” class CVEs completed, 34 were transferred to the RN

via Lend-lease, leaving only eleven in USN service. These

were joined by the follow-on “Casablanca” class, fifty of

which were completed and commissioned from late 1942 to

mid-1944—the largest class of aircraft carriers ever

constructed. The “Casablancas” were designed from the keel

up as carriers, though built to mercantile production

standards. They were smaller than the “Bouges” and due to

manufacturing bottlenecks received reciprocating engines instead of steam turbines, so that

their range was less. As completed their armament consisted

of one 5in/38 DP, four twin 40mm AA and twelve single 20mm

AA. By 1945, however, both classes had a pair of 5in/38s,

eight to ten twin 40mm and up to 27 20mm.

To meet the pressing need for

aircraft carriers in 1942, the USN also decided to convert

four Type T-3 naval oilers into escort carriers. These ships

constituted the “Sangamon” class and they were considerably

larger than the “Bouges”

and “Casablancas,”

with a much longer flight deck a more powerful catapult and,

thanks to their oil tanker origins, an exceptionally wide

radius of action. The Sangamons” successfully filled

the gap in the Pacific until sufficient CVs and CVLs became

available, and they were the prototypes for the final

wartime CVEs, the “Commencement Bay” class. These ships were

based on the T-3 tanker hull but were built as carriers

from the keel up. Thirty-three were ordered but only nineteen were

eventually commissioned in the USN, some postwar. The rest

were canceled. Those commissioned during the war (late

1944-1945) saw little service before VJ-Day.

USS

Chenango (CVE 28) of the "Sangamon"

class. She, her three sisters and the

follow-on "Commencement Bay" class were the

largest and most capable of the CVEs.

(Naval Heritage & History Command)

In US Navy service, the jeep

carriers carried between nineteen and 33 fighters and

bombers. In late 1943-early 1944 the “Bogue” and

“Casablanca” classes serving in the Atlantic shipped an air

group consisting of nine F4F Wildcat fighters and twelve TBF

Avenger torpedo bombers; if operating in the Pacific their

air group consisted of eighteen F4Fs and twelve TBFs. For

the larger “Sangamon” class, the air group consisted of 24

F4Fs and nine TBFs. Later in the war the four “Sangamons”

and the follow-on “Commencement Bay” class had air groups

consisting of eighteen F6F Hellcat fighters and twelve TBFs.

Thanks to their larger hangers and longer flight decks, they

were the only CVEs capable of operating the F6F and the

Vought F4U

Corsair, both of which were

considerably larger than the F4F. To speed

flight deck operations, the “Sangamons” were refitted with a

second catapult and the “Commencement Bays” were completed

with two catapults.

An FM-2 Wildcat (General Motors-produced

version of the F4F-4) of VC-24, the USS Block Island

(CVE-21) air group.

(Naval Heritage & History Command)

Though it was obsolescent as a

front-line fighter by 1943, the Wildcat acquired an extended

lease on life aboard the jeep carriers. The F4F-4 model with

folding wings economized on space in the hanger and could

take off from the CVE’s relatively short flight deck without

catapult assist. Thus the Wildcat remained in production

right to the end of the war. Some 8,000 were produced,

nearly 1,000 of which were supplied to Britain’s Royal Navy.

The Avenger, which was the largest single-engine aircraft

operated by the Navy during the war, required catapult

assist for takeoff. Its enclosed weapons bay could

accommodate bombs or depth charges in place of a torpedo,

and the TBF could also carry air-to-surface rockets

underwing. Aboard CVEs in the Atlantic, the Avenger served

primarily as an antisubmarine aircraft, while in the Pacific

it was also employed aboard CVEs as a light bomber and

ground attack aircraft.

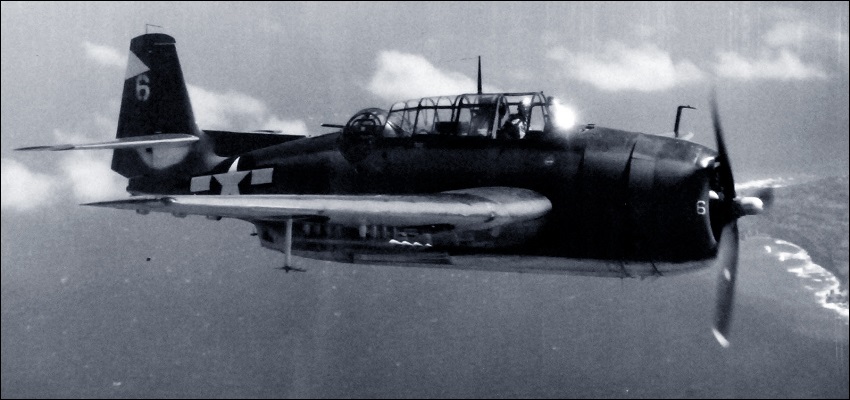

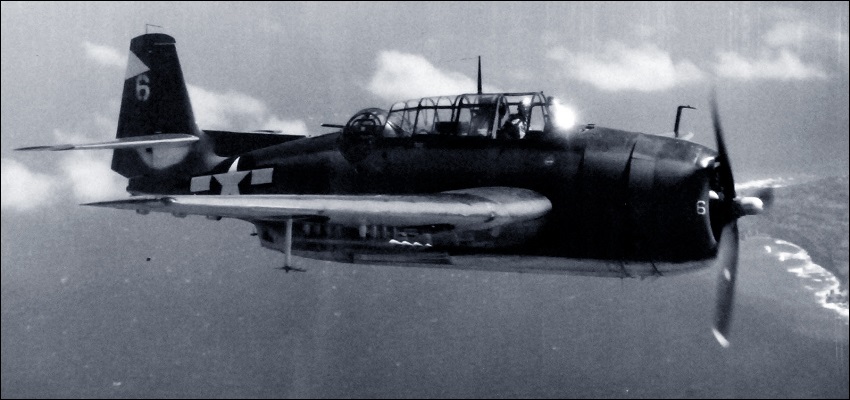

A TBM-3 Avenger (General Motors-produced

version of the TBF), carrying air-to-surface rockets

underwing. (NavSource Online)

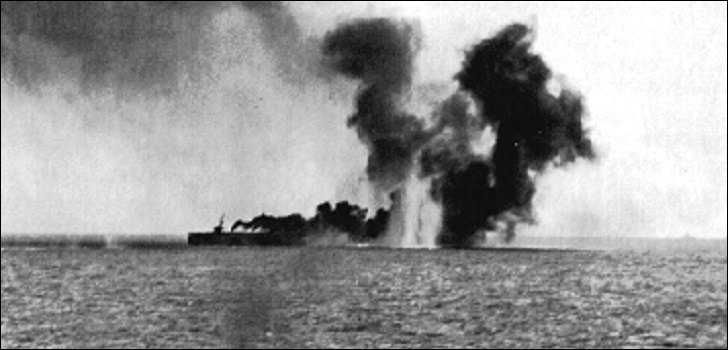

The introduction of the CVE

revolutionized antisubmarine warfare: For the first time,

convoys could be provided with on-the-spot air support. In

combination with destroyer escorts, they also formed

independent hunter-killer groups. These consisted of a CVE

and several escorts, initially older fleet destroyers like

the four-piper

escort conversions, later

destroyer escorts.

Hunter-killer groups served as convoy escorts and also

operated independently, locating and destroying U-boats on

passage to and from the Atlantic. This roving hunter-killer concept

proved most successful. The ever-present possibility of air

attack compelled the U-boats to remain submerged during

daylight hours, greatly impeding their operations. If caught

on the surface by aircraft from a CVE, they were likely to

be damaged or sunk in short order. The hunter-killer group

formed around USS Bouge

(CVE-9), for example, sank

or damaged fifteen German and Japanese submarines between

April 1943 and April 1945. On 4 June 1944, the group formed

around USS

Guadalcanal (CVE-60)

captured U-505.

The U-boat was first damaged by depth charges from the

destroyer escort USS

Chatelain

(DE-149) and when it surfaced boarding parties from the

escort and the carrier took control of her before she could

be scuttled. U-505

was taken in tow by

Guadalcanal and

brought into port at Bermuda. She was the first enemy vessel

captured on the high seas by the USN since 1815 and is now

on display at the Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago,

Illinois.