● ● ●

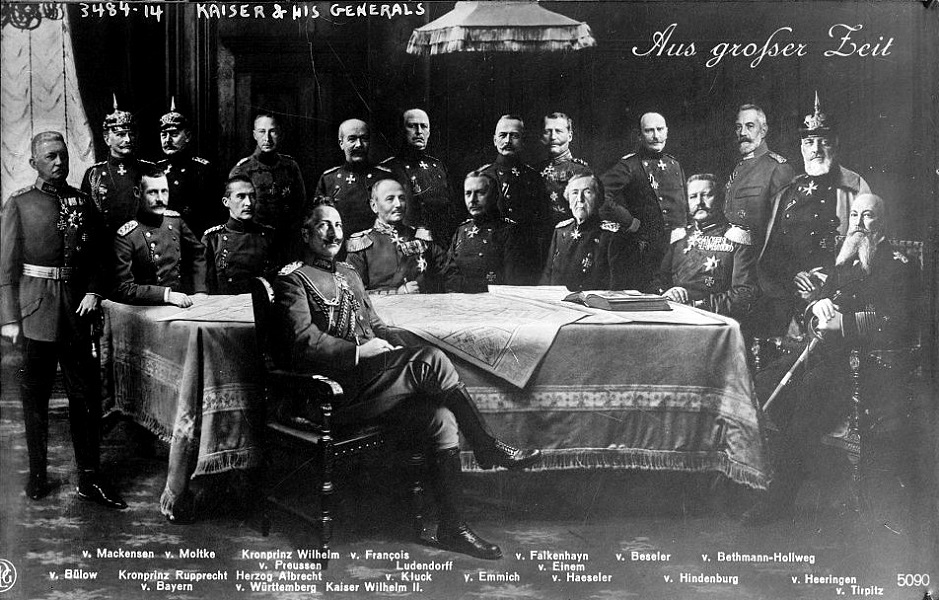

When

the guns opened fire in the summer of 1914 no one, not even

the generals, really knew what to expect. The last general

European war had been fought in 1815, a year in which the

military state of the art was represented by the Brown Bess

musket. With this weapon, generally considered to have been

the finest of its type, a well-trained soldier could load

and fire two or three rounds a minute. The effective range

of the Brown Bess and similar smoothbore muzzle-loading

flintlock muskets was about 80 yards. As for the artillery,

in 1815 it consisted mostly of cast bronze muzzle-loading

smoothbore cannon of various types, such as the French

12-pounder field gun. This weapon had an effective range of

about 1,000 yards with solid shot and 500 yards with

canister. Its rate of fire was one or two rounds a minute.

The main weapons of the cavalry arm were the sword, the

saber and the lance.

The

armies that employed these weapons were of modest size. At

Waterloo about 75,000 French troops fought some 120,000

allied troops. The battles of the Napoleonic era were,

indeed, larger and more sanguinary than those of the

preceding Seven Years War. But a soldier of the army of

Frederick the Great would not have felt entirely out of

place at Austerlitz or Borodino. Between the general

adoption of the flintlock musket around 1700 and the defeat

of Napoleon, military technology had remained relatively

stable. Such improvements as occurred were incremental, for

instance the replacement of wooden musket ramrods by more

durable iron ones.

Most of the

states that fought the wars of that era still had roots in the

feudal and absolutist past. What would come to be called the modern

nation-state was best exemplified by France, with profound

implications for the art of war. The French Revolution gave birth to

a concept of national citizenship embodying both rights and duties,

and foremost among the latter was the duty of bearing arms in

defense of the nation. The citizen-soldiers of the French armies

were not mercenaries or press-ganged peasants, as in the Russian,

Prussian and Austrian armies. The rigid discipline and draconian

punishments that kept the soldiers of those states under control

were not necessary to make French soldiers fight. Patriotic ardor

powerfully reinforced traditional military discipline, and this was

reflected in new, flexible battlefield tactics that Napoleon was to exploit to

the fullest. And wherever the French armies marched, they brought

with them the ideas of the French Revolution—nationalism prominent

among them.

Europe

on the eve of the Great War (Department of History, USMA West Point)

Between 1815

and 1914, the growing national consciousness of its peoples

transformed the face of Europe. The Greek War of Independence, the

Polish revolts, the revolutions of 1830 and 1848, Italian and German

unification, all in their various ways undermined the old order.

This was particularly true as regards the multinational Russian,

Austrian and Ottoman empires. The Ottoman Empire's gradual decline

was a major source of European tension in the second half of the

nineteenth century, and the Habsburg Monarchy's fear of South-Slav

nationalism was a major contributor to the crisis that led to war in

1914.

War in the age

of the nation-state meant national mobilization and it was the

Industrial Revolution, advancing pari passu with nationalism, that

had made this possible. The growth, development and diversification

of industry—coal and oil, steam, steel, electricity and

chemistry—provided the material means to arm, equip, transport and sustain the

new mass armies. National conscription was managed by the

administrative apparatus of the modern state. The railroad and the

telegraph facilitated the mobilization and movement of armies. And

the great increase in the population of Europe between 1815 and 1914

supplied vastly more manpower for the armed forces.

Thus by

1914 the muskets of Waterloo had been replaced by bolt-action magazine rifles (rate of fire 6-8 rounds per

minute, effective range 800-1,000 yards) and the machine

gun. Smoothbore muzzle-loading cannons had been replaced by

breech-loading, recoil-stabilized field guns and howitzers

firing high-explosive and shrapnel shells to ranges up to

10,000 yards. In the cavalry arm, though the sword and lance

still held sway they were now supplemented by rifles and

machine guns. And the armies themselves were far larger. In

1914 France mobilized nearly 3 million men to bring its

peacetime army of about 800,000 up to war strength. The

mobilized German Army contained 4.5 million men. What would

happen when such gigantic armies clashed, no one could say.

Nevertheless it was the business of the generals and general

staffs who controlled these forces to plan for war. In

Germany, Austria-Hungary, France and Russia this planning

proceeded on the assumption that the impending war would be

decided in a single campaign of several months. There were

reasons to think that modern Europe could not sustain a long

war. Many people felt that Europe’s economic

interdependence, the vast cost of modern war and, perhaps,

the social unrest accompanying it would soon bring any

fighting to a halt. So, having read their

Clausewitz, the

general staffs of the major continental powers thought and

planned in terms of decisive battle.

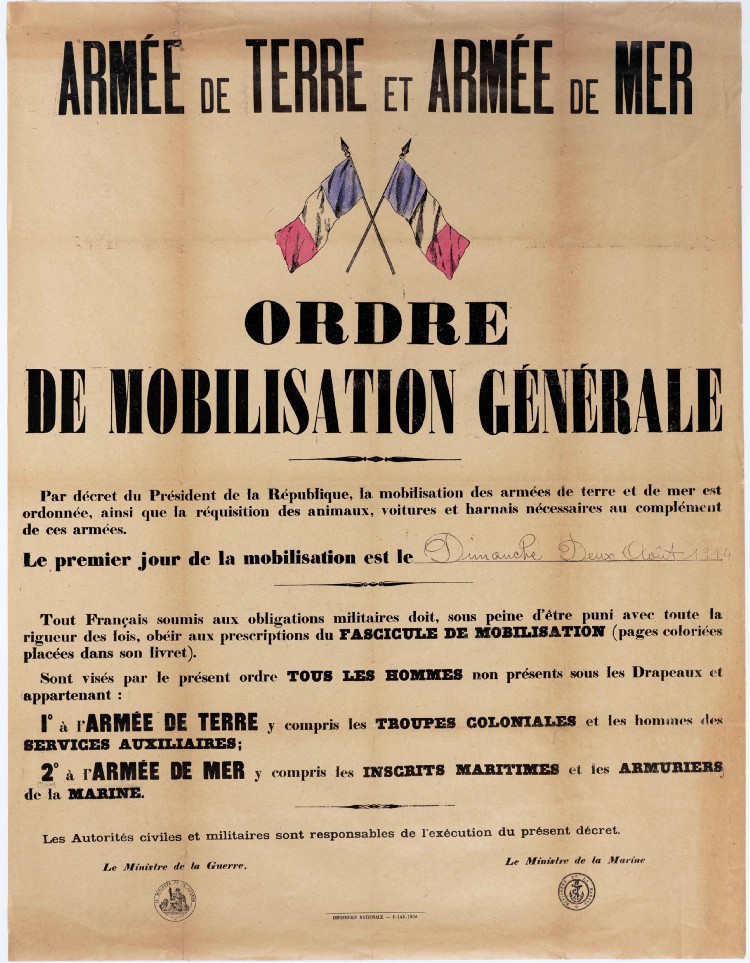

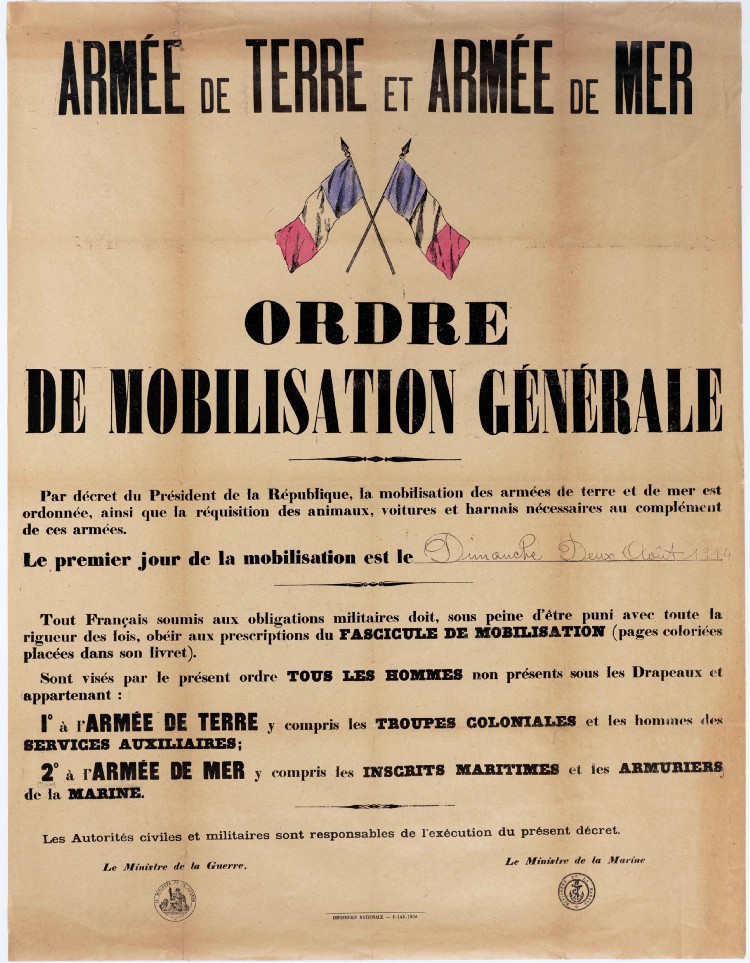

The announcement of French

mobilization, 1 August 1914

More

precisely, they planned in terms of a series of

battles whose cumulative effect would be decisive. Military leaders

perceived that no single battle would determine the outcome

of the next war. Their planning thus focused on the

mobilization and initial deployment of their forces. All the

major European powers, Britain excepted, employed a similar

military system. Their peacetime armies were relatively

small, consisting of long-service officers, NCOs and

soldiers whose main business was to train the annual intake

of conscripts. These latter served for two or three years,

afterwards passing into the first-line reserve where they

remained for six or eight years. Thereafter they passed into

the second-line reserve, called the Territorial Reserve in

France and the Landwehr in Germany. Upon mobilization

the first-line reservists would be used to fill out the

units of the active army and to form additional units. The

second-line reservists would be formed into units for

employment on subsidiary duties: rear-area security,

guarding prisoners of war, garrisoning fortresses, manning

quiet sectors of the front, etc. By this means an army of

millions could be raised in three weeks to a month.

Prewar

military planning thus concerned itself with two problems:

(1) mobilization and organization of the army; (2) its

deployment to the zone of active operations. It was the

second problem that most exercised the minds of the general

staffs. After reporting to their regimental depots,

mobilized reservists would be uniformed, equipped,

armed and organized into units. But then they would have to be

transported by rail to the zone of operations. The

complications involved in this process were formidable. All

general staffs included railway sections whose specialists

concerned themselves exclusively with the rail scheduling

necessary to bring off a smooth deployment. In 1914 the

German Army’s western deployment required 11,000 troop

trains. At the height of the effort, trains were crossing

the Rhine River bridges at two- or three-minute intervals.

Men

realized that a mistake made in the initial deployment of

the army could not be rectified. Millions of soldiers with

all their horses, guns, ammunition, supplies and impedimenta

could not summarily be moved from place to place like

counters on a game board. Getting the initial deployment

right thus became the focus of prewar planning. The most

famous example is the German

Schlieffen Plan, that famous right hook—which

actually was a scheme of deployment, not a battle plan. The Chief of the Great

General Staff, General von Schlieffen, poring over his maps

at the turn of the century, sought sufficient space for the

western deployment of the German Army in full strength. His eye fell

inevitably on Belgium, “the cockpit of Europe.” There a

powerful attacking force would find ample ground on which to

array itself, pressing down

the Channel coast into France, turning the left wing of the

French army in a series of engagements whose cumulative

effect would bring decisive victory south and west of

Paris.

Similar planning had been going on in the offices of all the

general staffs of the European powers. Now war had come; the military

plans thus developed, the military instruments

thus forged, were about to be tested in battle.