● ● ●

For

clarity, German units are rendered in italics.

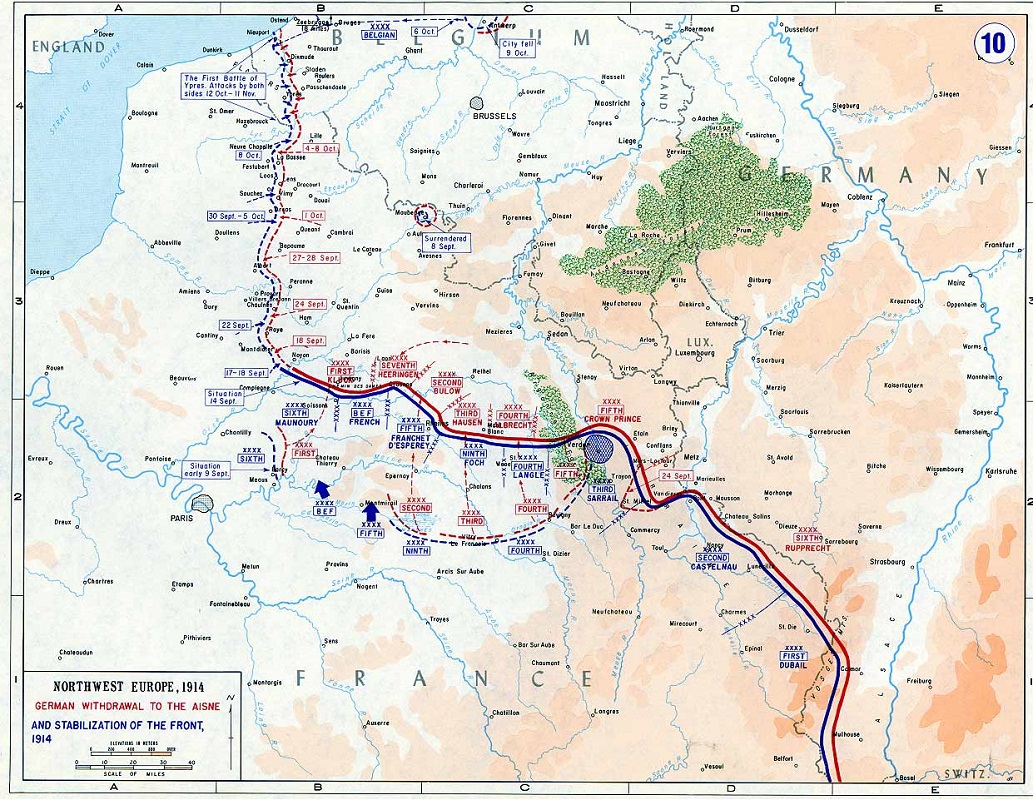

Though the Battle of the Marne was

an Allied victory, the German Army was not decisively

defeated. The retreat of its right wing to the Aisne River,

ordered on 8 September, was carried out in good order and by

13 December the Germans had taken up an entrenched position

on that line. The Allies’ followup was slow, due both to

caution and the troops’ fatigue, and their attacks on 15-16

September were repulsed.

But beyond the Aisne position lay

open country and the opposing commanders, General Joseph

Joffre and General of Infantry Erich von Falkenhayn, who had

by now replaced Moltke as Chief of the OHL, both sought

victory by turning the enemy’s open western flank. To that

end, both sides began transferring troops from east to west.

The French had begun to do so as early as 2 September, in

line with Joffre’s inflexible determination to resume the

offensive at the earliest possible moment. The Germans soon

followed suit, taking troops from their left flank and also

from Belgium to constitute an attacking force on their

right. Thus between mid-September and mid-October there

ensued a series of encounter battles as each side sought

without success to envelop the other’s open flank. These

seesaw battles—so-called Race to the Sea—extended the front west, then north, until

the Channel coast was reached in the vicinity of Nieuport.

Here and a little farther south around the town of Ypres the

Germans were to make a final bid for the decisive victory

that had eluded them on the Marne.

The "Race to the Sea"

(Department of History, USMA West Point)

It will be remembered that early in

the campaign the Belgian Army had withdrawn into the

fortified camp of Antwerp, from which position it

constituted a threat to the rear of the advancing German

right wing. The Belgians, indeed, had conducted several

sorties out of their fortifications in an attempt to support

the British and French fighting on the main front. Some on

the Allied side, Winston Churchill prominent among them,

hoped that that the Belgian Army would prove able to hold

Antwerp indefinitely, placing such pressure on the Germans

as to compel their withdraw to the east. The First Lord of

the Admiralty made the defense of Antwerp his personal

crusade, extemporizing a brigade of Royal Marines for

dispatch to the city and agitating for further British

reinforcements. These were sent and Churchill himself spent

considerable time in Antwerp: a diversion from his principal

duties as civilian head of the Royal Navy that attracted

much criticism.

But it soon became clear that the

Antwerp position was untenable. Alarmed by the Belgian

sorties, the Germans reinforced their besieging troops and

opened a heavy bombardment on 28 September. Things quickly

went from bad to worse for the defenders and on 10 October

the Belgian Commander-in-Chief, King Albert, ordered his

army to quit Antwerp and retire west along the Channel

coast. With the Belgians went the British defenders: the

Royal Marine Brigade and the Royal Naval Division—the latter

made up of reservists excess to the RN’s requirements,

organized as infantry. Along the way they linked up with

further British troops: the 7th Division and the 3rd Cavalry

Division, which had been landed west of Antwerp at Zeebrugge.

The remaining garrison capitulated, 30,000 mostly Belgian

soldiers being taken prisoner. But the bulk of the Belgian

and British troops survived to reach the line of the Yser

River, just east of Nieuport, on 14 October. Meanwhile the

BEF was completing its transfer from the Allied center to

Belgium, this to position it closer to its main base, Le

Harve on the Channel coast.

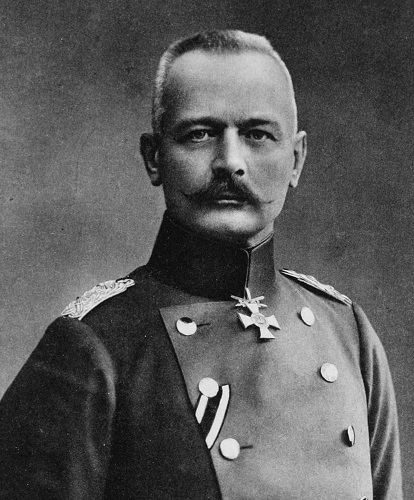

General of Infantry Erich

von Falkenhayn, Moltke's successor as Chief of the OHL (Bundesarchiv)

For his part Falkenhayn remained

intent on a war-winning offensive. His intention was to

deliver an “annihilating blow,” crushing the Allied left

flank and driving along the Channel coast to capture Dunkirk

and Calais. This, he calculated, would knock out the British

Army and compel the French to ask for terms. The German

attack was to be two-pronged: Fourth Army (Duke

Albrecht of Württemberg; fifteen

infantry divisions) would strike across the Yser

while Sixth Army (Crown Prince

Rupprecht of Bavaria; eleven infantry divisions, six

cavalry divisions) would capture the town of Ypres and

strike west. Both German armies had been reconstituted and

reinforced after their transfer from the left wing. The

reinforcements for Fourth Army included four newly

raised reserve corps (eight divisions) whose troops,

sketchily trained and poorly equipped, were young volunteers

who’d rallied to the colors in August. They were to suffer

heavily in the ensuing battle.

The overall commander on the Allied

side was General Ferdinand Foch, whom Joffre had appointed

commandant le groupe des Armées

du Nord (commander of the group of northern

armies) on 4 October. Though he had no formal authority over

the British and Belgian forces in Flanders, Foch was able to

obtain their cooperation and it was he who coordinated the

defense. The Allied order of battle embodied the Belgian

Army (six infantry divisions, a French infantry division,

six battalions of French marines) and the French Eighth Army

(twelve infantry divisions, eight cavalry divisions) holding a line south from

the Channel coast. The BEF (seven infantry divisions, three

cavalry divisions) held Ypres area, its left flank linking

up with French forces

south of Ypres.

General Ferdinand Foch,

who coordinated the defense of Ypres and the Channel coast

(Musée

de l'Armée)

Belgian Flanders is a mostly flat

plain enclosed by a system of canals linking the region’s

major towns. On the Channel coast the ground is at sea

level, fringed by sand dunes. Farther inland the terrain is

mostly meadow cut by canals, dykes, drainage ditches, and

roads laid on built-up causeways. A line of low hills

stretches east from the town of Cassel to Mount Kemmel. From

there, a low ridge stretches to the northeast, past the town

of Ypres then curving north and northwest to the plain. In

1914 the area south of the La Bassée Canal around Lens and

Béthune was a coal-mining district studded with slag heaps,

pit-heads and miners' cottages. North of the canal, the city

of Lille and its environs constituted a manufacturing area.

Otherwise the land was given over to agriculture,

crisscrossed by hedgerows, roads and narrow tracks. Because

the water table in Flanders is so close to the surface, the

ground in spring and summer often becomes an impassable

morass. Overall, Flanders was a far-from-ideal setting for

offensive military operations. Lack of observation limited

the effectiveness of artillery, while the many

obstructions—canals, streams, villages, slag heaps,

etc.—hampered advancing infantry and made cavalry operations

virtually impossible.

The First Battle of Flanders ran

from ran from 18 October to 30 November 1914. For both

sides, it was a sanguinary introduction to the realities of

warfare between mass armies armed with modern weapons. And

for the British in particular, the names associated with

Flanders—Ypres, Passchendaele, Gheluvelt, Polygon Wood—would

be inscribed with letters of scarlet in the regimental

histories of the BEF.