● ● ●

Note on Comparative

General Officer Ranks

Rank

structures and titles in the various armies of the Great War were

not exactly equivalent. In the French Army there were only two

permanent general officer ranks: General of Brigade (Général de

Brigade) and General of Division

(Général de Division).

A General of Army Corps (Général de Corps d'Armee)

or a General of Army (Général d'Armee)

was actually a General of Division appointed to that higher

command: He wore the insignia and used the title of his appointment

during his tenure in command only. The title of Marshal of France (Meréchal

de France) was technically not a

rank but an honorific, conferred for distinguished service.

In the German

Army all general officer ranks were permanent. These were

Colonel-General (Generaloberst), General of Arm or Branch (General

der Waffengattung), Lieutenant-General (Generalleutnant)

and Major-General (Generalmajor).

A

General of Arm or Branch used the name of his parent branch of

service, e.g. General of Infantry (General

der Infanterie). The highest Army rank was Field Marshal (Generalfeldmarschall);

in 1914 no general officer on the active list held this rank, which

by custom was only conferred for distinguished service,

usually in wartime.

Kaiser Wilhelm II held it ex officio as monarch and "Supreme

Warlord."

In the British Army also general

officer ranks were permanent. These were Field Marshal, General,

Lieutenant-General, Major-General and Brigadier-General. The Belgian

Army had two general officer ranks: Lieutenant-General (Lieutenant-général)

and Major-General (Major-général)

● ● ●

For clarity, German formations

are rendered in italics.

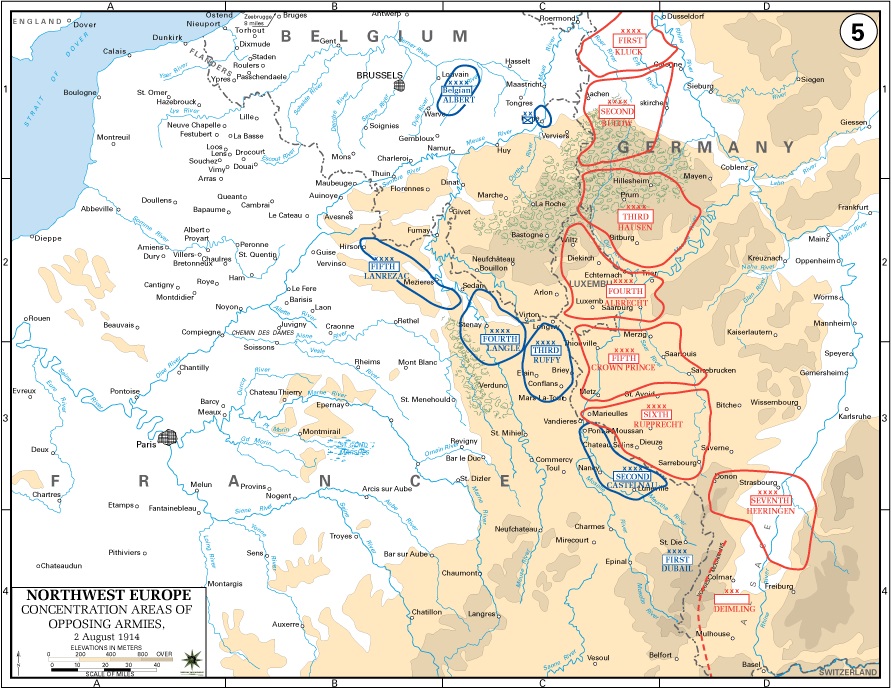

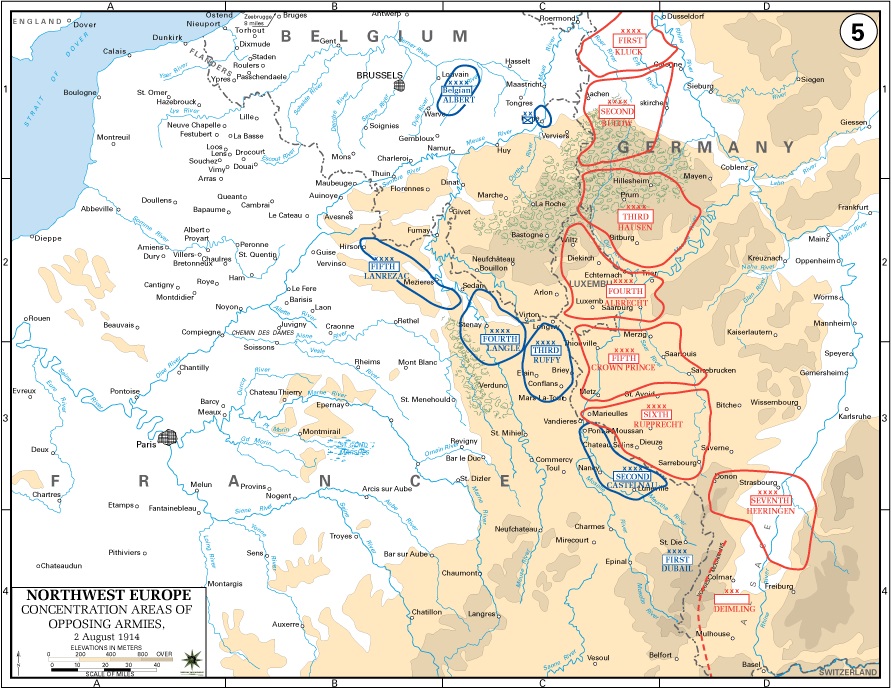

The first

campaign of the Great War in the west was dominated by two factors:

Germany’s amended

Schlieffen Plan and France’s Plan XVII. The latter was a

straightforward proposition: a mobilization and deployment scheme

anticipating an all-out offensive, the objective of which was to

clear German forces from Alsace and Lorraine and carry the French

armies to the Rhine River. For this purpose France’s five field

armies were to be concentrated between the Belgian and Swiss

borders. On the left, Fifth Army was to act as a flank guard in case

the Germans attempted an attack through Luxembourg and southern

Belgium. The remaining armies—from left to right the Fourth, Third,

Second and First—were to drive into Lorraine. To the south of this

main effort, a detached corps would advance into Alsace. (Map 5

shows the deployment areas of the French and German armies on 2

August. Note how the concentration of forces on the German right

flank overlaps the French left.)

Department of History, USMA West

Point

Though the

French commander-in-chief, General Joseph Joffre, recognized the

possibility of a German flank attack through southern Belgium he

never seriously considered the idea of a large-scale German maneuver

on the pattern of the Schlieffen Plan. Joffre reasoned that the

Germans possessed insufficient first-line divisions for such an

audacious operation. Discounting the value of his own reserve

divisions, he failed to foresee that the Germans would use theirs in

an offensive role. Thus the Fifth Army, supplemented by the British

Expeditionary Force (Field Marshal Sir John French), seemed to him

adequate to secure the French left flank. He paid no attention to

the warnings of Fifth Army’s commander, General

Charles Lanrezac, that the Germans were deploying in great strength

along the Belgian border. Lanrezac was uncomfortably aware that

until the BEF appeared, there would be nothing to

the left of his army than a thin

screen of second-line Territorial troops along the Franco-Belgian

border.

Joffre's strategic

misjudgment was compounded by some serious tactical deficiencies. In the

years prior to the war the French Army had fallen under the sway of

a faction that preached the doctrine of the offensive in its most

extreme form. All professional soldiers in Europe shared this view

to some extent, but in France the offensive was embraced with an

almost religious fervor. Relying on the bayonet and an aggressive

spirit supposedly native to the French soldier, the troops would

attack in dense formations, supported by the rapid fire of the

excellent French 75mm field gun, overrunning the enemy in one

audacious rush.

There were,

indeed, doubters and critics. Some argued that insufficient

attention was being paid to infantry tactics or to the problems of

coordination between infantry and artillery. Others pointed to the

French Army’s material deficiencies, especially in medium and heavy

field artillery. These criticisms the prophets of the offensive

waved away with assurances that French cran—guts—would

compensate for any such minor shortcomings. To suggestions that the

traditional infantry uniform—dark blue coat, madder red

trousers—should be replaced by something less conspicuous, they

replied scornfully: Les pantalons rouges, c'est la France!

Department of History USMA West Point

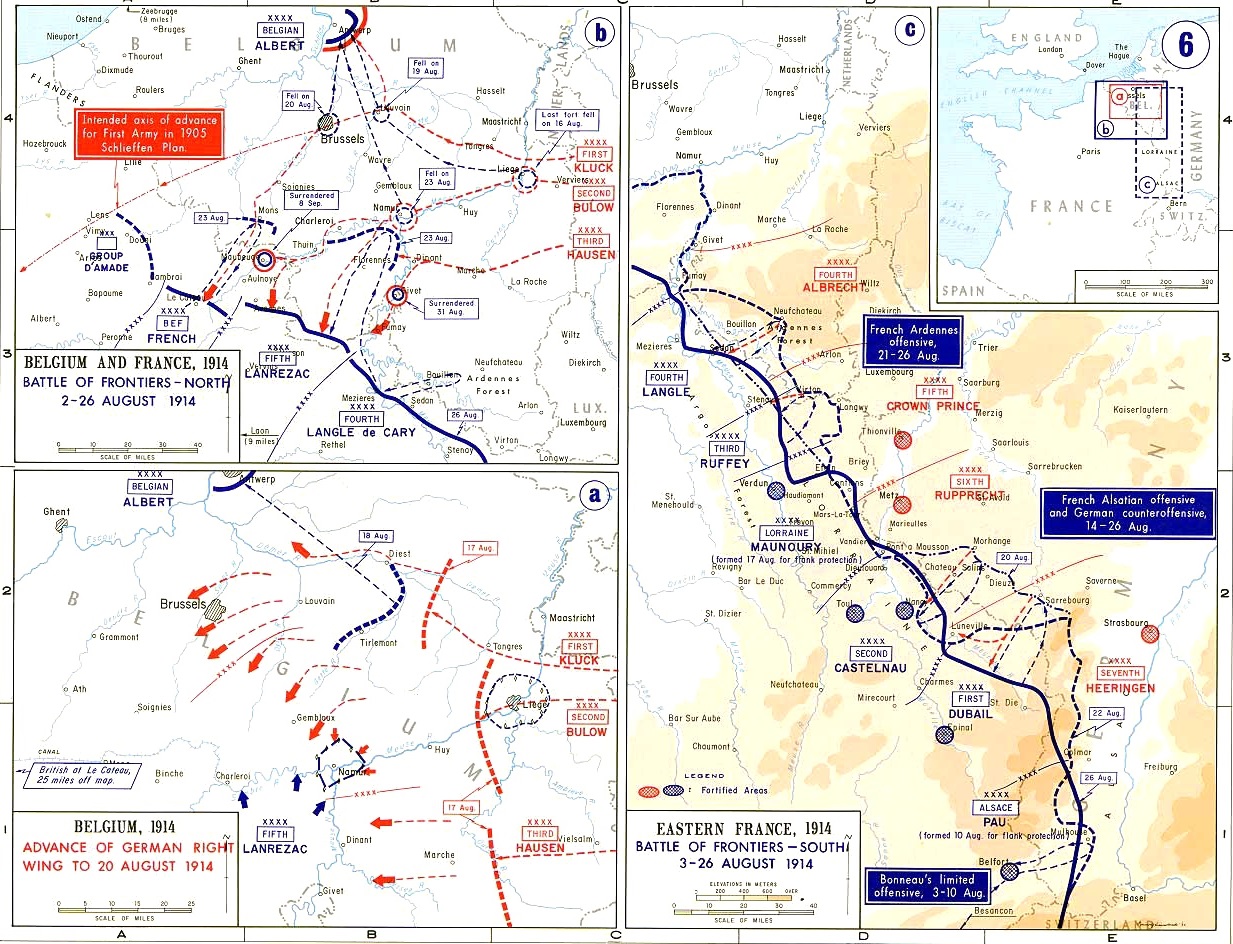

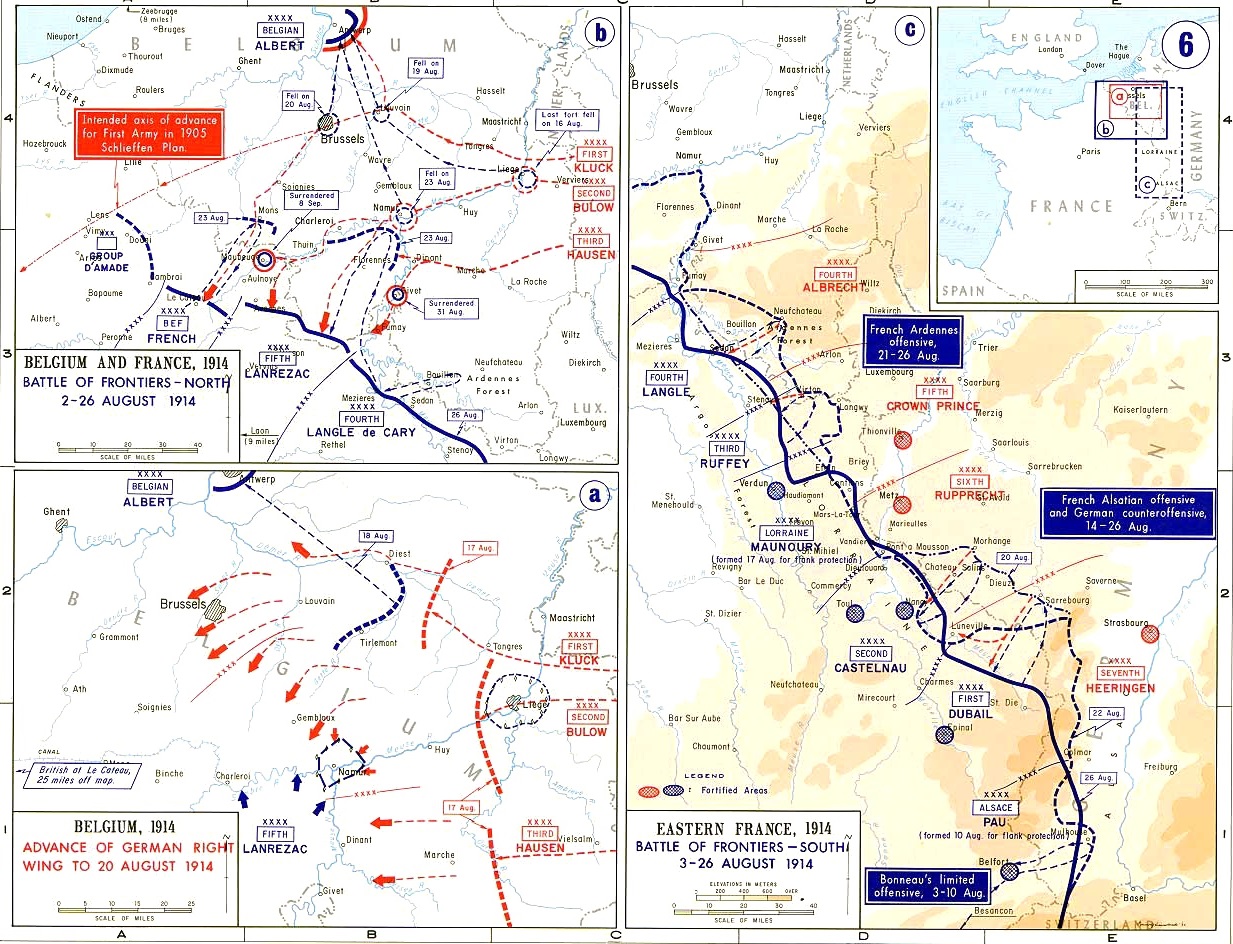

Given this

background, what happened when Joffre launched his offensive seems

sadly inevitable in retrospect. Between 14 and 23 August the French

First Army (General Augustin Dubail) and Second Army (General

Édouard de Castelnau) were bloodily repulsed at all points in

Lorraine. Attacking in close order, bayonets fixed, regimental

colors and saber-waving officers in front—sometimes even with

regimental bands playing—the French infantry were mowed down in

droves by rifle, machine gun and artillery fire. Against Sixth

Army (Colonel-General Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria) and

Seventh Army (Colonel-General

Josias von Heeringen), whose

troops occupied well-sited defensive positions, the 75mm field gun proved

ineffective. Only in Alsace, where the defending Germans were

weakest, did the French enjoy some measure of success—but the ground

gained there had mostly to be yielded back after the disaster in

Lorraine.

Thus

preoccupied with the fortunes of his attacking armies, Joffre was

slow to recognize the danger looming on his left flank. The

information that did come to hand convinced him that the Germans

were attempting no more than the anticipated flank attack through

southern Belgium. He therefore ordered Fifth Army to sidestep to its

left, establishing touch with the BEF, now in the field with four

infantry divisions, a cavalry division and an independent cavalry

brigade. (The BEF was supposed to have been six infantry divisions

strong but an invasion scare led the British government to hold two

divisions and some cavalry back.) The Third Army (General

Pierre Ruffey) and Fourth Army (General Fernand de Langle de Cary)

were ordered to advance into the Ardennes, there to blunt the German

advance. The French attack in this sector began on 21 August. But as

in Lorraine the attacks, delivered in close order against

well-posted defenders, broke down amid heavy casualties. (Map 6c

shows the French offensives in Lorraine and the Ardennes.)

Farther north

the

German right wing, consisting of First, Second and Third

Armies, was advancing through Belgium. First Army

(Colonel-General Alexander von Kluck) initially moved northwest,

engaging the Belgian Army (six infantry divisions and a cavalry

division) on 17 August. After a hard-fought action, the Belgian

commander, King Albert, ordered his army to withdraw into the

fortified position around the port of Antwerp. Thereupon First Army

turned left toward Brussels; the Belgian capital fell on 20

August. Meanwhile Second Army (Colonel-General Karl von Bülow)

and Third Army (Colonel-General Max von Hausen) advanced into

the gap between the Belgians and the French Fifth Army.

Fifth Army, stretching its left flank northward, found itself badly

outnumbered and was driven back by Second and Third Armies.

This heavy pressure on the French left also forced Fourth Army

to give ground.

The advance of First Army

brought it into contact with the BEF, deployed in defensive

positions around the town of Mons. After some preliminary cavalry

skirmishes, the Germans attacked in strength on 23 August,

mainly in the sector held by the BEF's II Corps (General Sir Horace

Smith-Dorrian). The rapid, well-directed rifle fire of the British

infantry inflicted heavy casualties on the Germans before weight of

numbers compelled the BEF to fall

back. Maps 6a and 6b show the advance of the German right

wing through Belgium and into

northwestern France up to 26 August. Note

how the line of advance of First Army began to diverge from

that laid down for it in Schlieffen's scheme of maneuver. His

attention fixed on the immediate tactical situation, Kluck deviated

from the plan in an attempt to outflank the BEF and Fifth Army.

German infantry of von Kluck's

First Army on the march in Belgium (Bundesarchiv)

The Battle of Mons was the

epilogue to a grievous and costly Anglo-French defeat. With the

repulse in the Ardennes and the advance of the German right wing the

Battle of the Frontiers was over, and the Great Retreat was

underway.

But at the

headquarters of OHL (Oberste Heeresleitung or Army High

Command) in

Koblenz,

General von Moltke was growing more and more uneasy. His armies had done

well thus far but where were the spoils of decisive victory:

prisoners, captured guns and impedimenta? What was happening at the

front? Moltke could not be sure. For as the field armies advanced,

communications between them and OHL became fitful and uncertain.

Radio, still in its infancy, was unreliable. Telegraphic and telephonic links

were mostly unavailable. Dispatches from the armies carried by couriers took

time to reach headquarters. And from the east, where a mere fraction

of the German Army stood in defense of East Prussia, there came grim

tidings of a massive Russian offensive. As the terrible

uncertainties accumulated, the nerves of the Chief of the Great

General Staff began to fray.