● ● ●

For clarity, German formations

are rendered in italics.

Up to 25 August, the German

offensive against France proceeded more or less according to plan.

The three armies of the German right wing had swept over Belgium

into France, pressing back the French and British forces in that

area. Meanwhile the French offensives in Alsace-Lorraine and the

Ardennes had been repulsed with heavy losses. But General von Moltke,

Chief of the OHL (Oberste Heeresleitung or Army High Command)

and de facto commander-in-chief, was far from easy in his mind.

It will be recalled that

Schlieffen’s original Aufmarsch I

West plan demanded the

strongest possible concentration of forces on the right.

Alsace-Lorraine was to be defended by a thin screen of reserve and

Landwehr troops, who would give ground if necessary in the

face of a French offensive. Moltke, however, worried about a French

breakthrough in this sector and took forces from the right wing to

bolster up the left. Then, as the offensive progressed, additional

troops had to be subtracted from the right wing to guard the

advancing armies’ lengthening lines of communications. The

Belgian Army, seven divisions strong, had withdrawn into the

fortified Antwerp position on the Channel coast. From this redoubt

it posed a threat to the German flank, requiring a corps to contain

it. And the series of engagements that the right-wing

armies had already fought cost them many casualties. Thus their

strength steadily diminished as they drew closer and closer to

Paris.

Colonel-General Helmuth Graf von

Moltke, Chief of the Great General Staff 1906-1914 (Bundesarchiv)

Moreover, the German right wing’s

axis of advance had diverged from that set down in Schlieffen’s 1905

plan. “Let the last man on the right brush the Channel with his

sleeve,” he had famously advised—but in the series of battles that

punctuated the Great Retreat, the three armies of the right wing

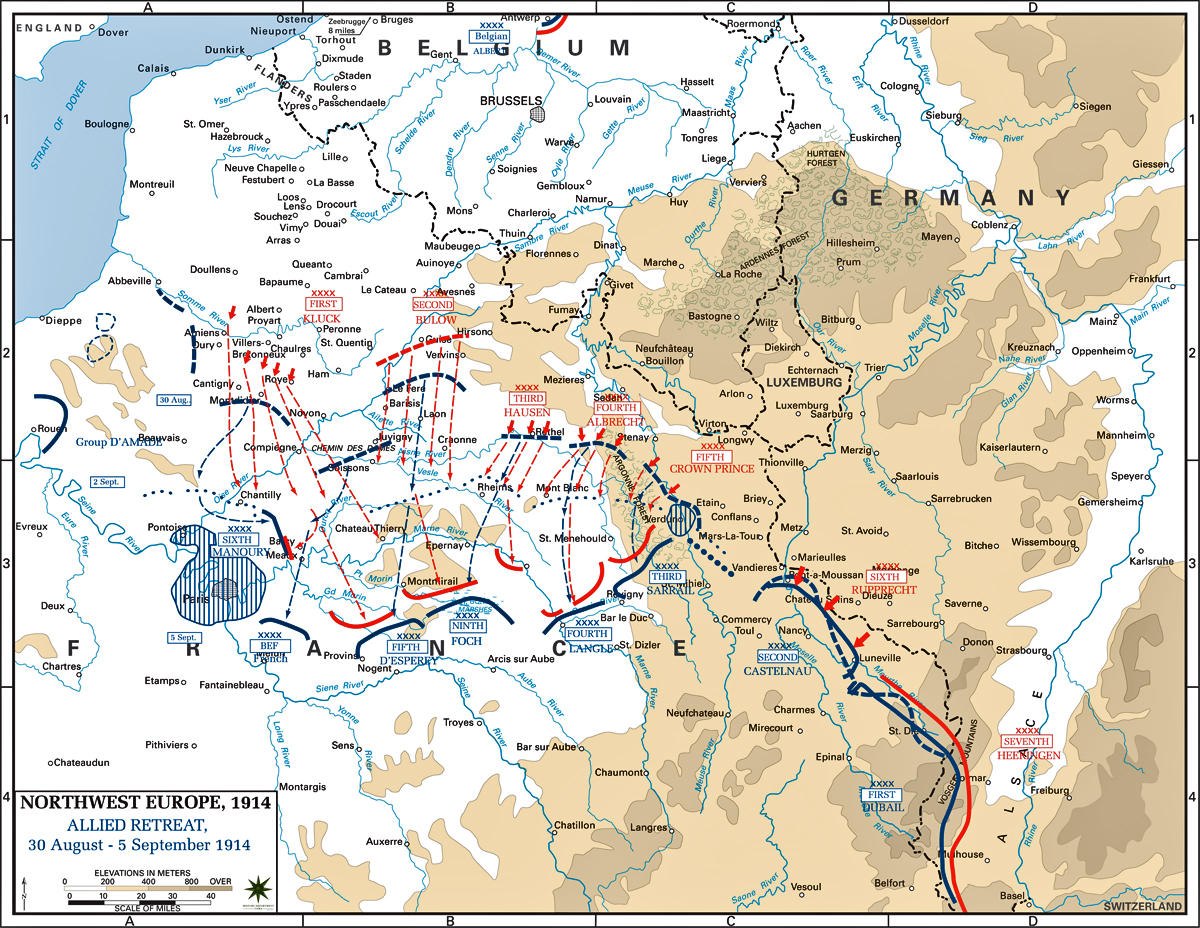

were drawn farther and farther to the southeast. The map below shows the

German advance between 30 August and and 5 September; note particularly First

Army’s sharp turn to the southeast. Sensing the gap between Fifth Army and the BEF, Kluck sought to exploit it. He was also anxious to

maintain

touch with Second Army on his left. These tactical

considerations, though not without validity, were incompatible with

Schlieffen’s grand design: the envelopment of both Paris and the

left wing of the French Army.

Another worry nagged at Moltke. In

far-off East Prussia the Russian Army had commenced a

major

offensive. Urged on by French pleas for the earliest possible

action, the Russians attacked without waiting for their mobilization

to be completed. Now two Russian field armies were advancing into

the ancient heartland of the Hohenzollern monarchy. The defenders,

embodied in Eighth Army, were outnumbered at least two to

one. Formally the plan was to yield ground in East Prussia if

necessary but patriotic sentiment and considerations of public

morale argued against this. As the Russian offensive developed pressure grew

on Moltke to send reinforcements east, and these could only come

from the western theater. Eventually he succumbed to that pressure,

taking three corps and a cavalry division from the armies of his

right wing and dispatching them to East Prussia—where they arrived

too late to take part in the Battle of Tannenberg.

Moltke also erred in giving in to

the pleas of the commanders of his left-wing armies for permission

to launch a counteroffensive against the French in Alsace-Lorraine.

Having won a great defensive victory they now were eager to go over

to the attack, tempting Moltke with visions of a double envelopment

of the French armies. He therefore sanctioned an attack by Fifth

Army and Sixth Army. But they made little headway

against the French, to whom the advantages of the defensive now

accrued, and suffered heavy casualties (see map below).

Map:

Department of History, USMA West Point

Still, between 25 August and 1

September the advance of the German right wing continued. By the

latter date the French line was bent at a ninety-degree angle with

Verdun as the hinge (see map above). But Moltke continued to fret, observing to his

staff that a truly decisive victory had so far eluded the German

armies. And because OHL was situated in occupied

Luxembourg, far from the fighting front, the exercise of command

from headquarters was increasingly difficult. Bit by bit, Moltke was losing his grip on the battle. And as the fog of

war enveloped him, the Chief of Staff's nerves began to fray.

This command

crisis was

compounded by a lack of intermediate headquarters between OHL and

the field armies. No provision had been made for army group commands

to coordinate, for example, the three armies of the right wing. In

their absence the movements of the individual armies became

disjointed, each commander maneuvering as he thought best. Attempts

to remedy this by putting one army commander in charge of

another, e.g. Bülow (Second Army) over

Kluck (First Army) caused more problems than it solved. This

command defect was to have fateful consequences.

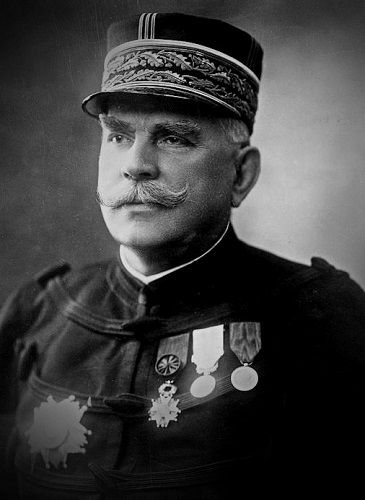

General Joseph Joffre, Commander-in-Chief of the French Army, 1914-16 (Wikimedia

Commons)

But on the

other side it was a different story. Despite the breakdown of his offensive the French

commander-in-chief, General Joffre, preserved an invincible calm.

His fixed intention was to stop the German advance and resume the

offensive at the earliest possible moment, and to that end he took

energetic and decisive action. Troops were transferred from Lorraine to

reinforce the French left wing, while north of Paris a new Sixth

Army was set up using reserve and Territorial divisions. If the

strain of battle affected Joffre he gave no sign of it. He kept to his normal working routine,

including three meals a day—which were taken in silence, all shop

talk being banned. Nor did he tolerate the failures and shortcomings

of subordinates. Generals thought to be lacking in aggression or

grit were ruthlessly sacked. Among them was the unfortunate

commander of the Fifth Army, General Lanrezac. His warnings that the

Germans were attacking in great strength through Belgium had been

ignored and his army, denied reinforcements, had nearly been

encircled and destroyed. Lanrezac's reward for being right when the

Commander-in-Chief was wrong was to be deprived of his command.

The stage was now set for a battle

whose outcome was to decide the whole course of the Great War in the

west. Still advancing, the armies of the German right wing sought to

envelop the French left flank. To that end First Army and

Second Army swerved southeast of Paris—a major departure from

Schlieffen’s plan. He had projected for

First Army a

southwesterly march, enveloping both Paris and the left flank of the

French armies. But now the German right wing was exposing its own

flank to an attack from Paris. The map above

shows the situation on the eve of the First Battle of the Marne;

note especially the axis of advance of First Army, passing

east of Paris—where General Joseph

Gallieni, the recently

appointed Military Governor of Paris, was organizing the

new Sixth Army.

It was a

critical moment, with the odds were closely

balanced. Despite increasing exhaustion and confusion the Germans

still held the initiative, they were still advancing, and one final

effort might give them Paris and victory. But as the French and

British left wing fell back, reinforcements began to reach it and

the front gradually consolidated itself some 25 miles south of the Marne River. The battle that soon

followed was to determine the whole subsequent course of the Great

War.