● ● ●

Trench warfare, that enduring

symbol of the Great War, was the product of a century of

political, economic, social and cultural development that

transformed the military art. The large increase in Europe's

population between 1800 and 1900 provided ample manpower for

the new mass armies, while industry developed and produced

in vast numbers new and deadly weapons of war: the magazine

rifle, the machine gun and the breach-loaded

recoil-stabilized cannon. Modern methods of administration

and finance facilitated national mobilization and

conscription, and enabled the armies to be supplied and

maintained in the field indefinitely. Strategic mobility

(the ability to move large bodies of troops from area to

area) was provided by the railroad and an increasingly dense

road net.

But once on the battlefield itself

the armies of 1914 were no more mobile than those of the

Napoleonic wars, moving on foot or horseback. Low mobility

and high firepower gave the defender an overwhelming

advantage, especially once the armies’ leaders grasped the

value of entrenchment. Even the most hastily constructed

field fortifications multiplied a soldier’s chances of

survival in combat—thus the trench systems on both sides

grew increasingly elaborate and complex. Moreover, the rival

armies were fighting over the same small area of Western

Europe where so many wars of the eighteenth and nineteenth

centuries had been fought. But now they were many times

larger, armed with much more lethal weapons, supported by

mobilized national economies. The result, as indeed a few

military thinkers had foreseen before 1914, was tactical,

hence strategic, stalemate.

After the brief period of mobile

warfare in 1914, trench warfare on the Western Front settled

into a fairly standard pattern. On both sides the defense

was usually based on three lines of trenches: a forward

line, a support line and a rear line. The trenches were dug

in a zigzag traverse pattern—this to prevent attackers in

occupation of one section from firing straight down the

trench—with firing steps for riflemen plus

protected positions for machine guns and observation posts.

Dugouts in the rear face of each trench provided

accommodation for company and battalion headquarters, supply

dumps, and shelter from artillery bombardment. The

front-line trench was protected by barbed-wire entanglements

many yards deep; the support line and the rear line served

as assembly points for reserves and fallback positions for

the front-line troops. The trenches were connected to one

another and to the rear area by communications trenches.

These enabled troops and supplies to be moved back and forth

without exposure to enemy observation and fire.

British troops in a

front-line trench (Imperial War Museum)

Behind the trench lines were troop

billets, artillery positions and brigade headquarters.

Farther back still were division and corps headquarters,

large supply dumps, rest camps, field hospitals—all the

supporting infrastructure required by modern armies.

Infantry battalions typically rotated between the trenches,

the billets and the rest camps. In sectors where an

offensive was to take place, the rear areas of both sides

would become crowded with reserves and vast quantities of

supplies—especially the hundreds of thousands of rounds of

artillery ammunition deemed necessary to support or resist

the “big push.”

Senior commanders on both sides

realized the inherent power of trench defenses, but that did

not lead them to conclude that offensive action was futile.

The search therefore began for some means of breaking the

trench stalemate, and the most obvious solution seemed to be

firepower. On the Allied side, the generals reasoned that

with enough artillery the enemy’s trench defenses could be

battered down, opening a way to the green fields beyond. The

costly and unsuccessful Allied offensives on the Western

Front in 1915 and 1916, culminating with the horrific Battle

of the Somme, only served to confirm this view. The attacks,

it was argued, had failed because the supporting artillery

was insufficient. More was needed—enough to physically

annihilate the enemy’s defense system in the sector of the

attack.

In fact, however, the French and

British generals had misdiagnosed the problem that

confronted them.

It was certainly possible to break

into the enemy's defenses, capturing a few lines of

trenches, and indeed this happened fairly often. But it

proved extraordinarily difficult to convert such a break-in

to a full breakthrough. One obvious problem was that the

laborious preparations for a major attack were easy to

detect, so that the element of surprise was lacking. Thus

forewarned, the defender had ample time to reinforce the

threatened sector. And once the offensive began, the

attacking troops of the first wave could be expected to do

no more than make good the break-in—an effort that would

decimate and exhaust them. The transition to a full

breakthrough required the commitment of reserves—and the

defender’s advantage in the management of reserves was the

real reason for the costly failure of all offensives

attempted by the Allies between 1914 and 1917.

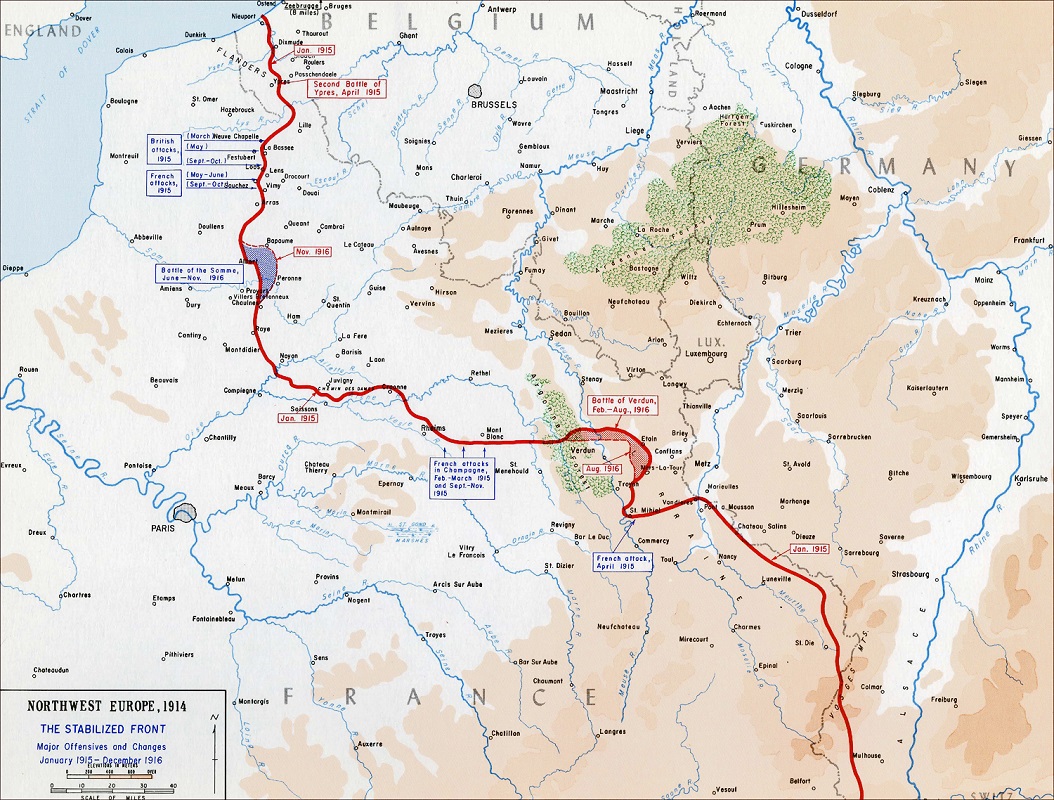

Department of History,

USMA West Point

Before sending their reserves

forward, the generals at their division, corps and army

headquarters needed accurate information from the front-line

units: Where had the attack succeeded; where had it failed?

But such information was slow to arrive. The primitive

radios of the day were too cumbersome to carry forward with

the attacking troops, telephone lines were all too easily

cut by shellfire, messengers could be killed, wounded, or

simply become lost. And when accurate information finally

did come to hand, the attacker’s reserves had to struggle

forward over ground devestated by prolonged

artillery bombardment. Meantime the defender could shift

reserves quickly by road and rail to the threatened sector

of his front. For both sides the battle became a race

against time—a race usually won by the defender.

But if the attacker suffered heavy casualties for nugatory gains, it was also

true that the price of a successful defense was high.

Holding the front-line trenches meant packing them with

troops, who were therefore exposed for a prolonged period to

the fury of bombardment. The Battle of the Somme in the

summer of 1916 is remembered as a disaster for the British

Army; less often remarked upon is its effect on the German

Army. The precise toll on the German side is still a matter

of some dispute, but a figure of 500,000 total casualties

cannot be far from the mark. Toward the end of the battle,

reports reaching OHL (the Supreme Command) indicated that

the Somme defenses were close to collapse, the trench system

itself in poor condition, the troops manning it worn out and

dispirited.

The Germans thus realized

that a new scheme of defense was required, and with

characteristic efficiency and attention to detail they

created one that proved highly effective in the conditions

prevailing on the Western Front. Having studied the tactical

lessons of the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05), the German Army

had been the first to appreciate the value of field

fortifications and they took advantage of wartime experience

to further refine their methods. In the new defensive system

that the German Army began to develop in 1916, strongly

garrisoned linear trenches were no longer to be the

principal fighting positions. The forward line of defense

was now an outpost position, lightly held, whose function

was to identify the attacker’s axis of advance and slow him

down. The troops manning this outpost line occupied small

dugouts, sited so as to take advantage of natural terrain

features, and were connected to the rear area by

communications trenches.

British heavy artillery in

action (Imperial War Museum)

The main defensive zone was based

on a series of mutually supporting strongpoints, held in

platoon or company strength, sited to dominate all avenues

of approach. Advancing between them, the attacking infantry

found themselves exposed to withering rifle and machine gun

fire, supplemented by pre-registered artillery and mortar

barrages. The strongpoints were constructed of

steel-reinforced concrete, making them invulnerable to all

but a direct hit by heavy artillery. Throughout the

defensive zone, barbed-wire entanglements and other

obstacles were sited to slow the enemy down and prolong his

exposure to the defenders’ fire. Behind the zone of

strongpoints the Germans posted local reserves usually in

company or battalion strength, whose task was to launch

immediate counterattacks against any enemy troops who

threatened to capture ground essential for the maintenance

of the defense. Finally, there was the general

reserve: so-called relief divisions

(Ablösungsdivisionen),

standing by in readiness to mount a full-scale counterattack

if necessary.

The depth of the main defensive zone was from three to four

and a half miles, depending on the terrain.

To streamline command and control,

the front was divided into sectors, in each of which a corps

headquarters was made responsible for administrative and

logistical tasks. Divisions were rotated in and out of these

sectors as necessary, with tactical control devolved upon

regimental and battalion commanders (Kampftruppenkommandeur)

in the battle zone. These commanders were given

discretion to maneuver their troops as necessary to deliver

local counterattacks or evade enemy fire.

Further enhancing the effectiveness

of their defensive system, the Germans were usually willing

to yield ground that might be difficult to defend, siting

their positions on the most advantageous terrain. In 1917

they even carried out a large-scale withdrawal from the

Somme to the Siegfriedstellung

(Siegfried Position), called the Hindenburg Line by the

Allies. This position, which became the keystone of the

German defenses on the Western Front, embodied all the

principles mentioned above and took five months to

construct. Though commanders were by no means agreed as to

the advisability of abandoning the Somme line, the course of

the battle from September to November seemed to leave no

other option. In March 1917 the withdrawal to the

Siegfriedstellung, code-named

Alberich Bewegung

(Operation Alberich) after

the evil dwarf in the

Nibelungenlied,

was carried out in good order. It shortened the

German line by some 25 miles, enabling a dozen

divisions to be taken out of the front as reserves. Similar

defensive positions were established for other sectors of

the front in preparation for the anticipated defensive

battles of 1917, for instance the

Flandernstellung in Belgium. The new system of

defense proved highly effective, frustrating the French and

British offensives on the Aisne and in Flanders. Though they

scored some tactical successes in the former offensive the

Allies were unable to achieve a breakthrough, and they

suffered 350,000 casualties against 163,000 inflicted on the

Germans—a disappointment that touched off a large-scale

mutiny in the ranks of the French Army. In Flanders, the

Third Battle of Ypres was ended on a similar note of

frustration.

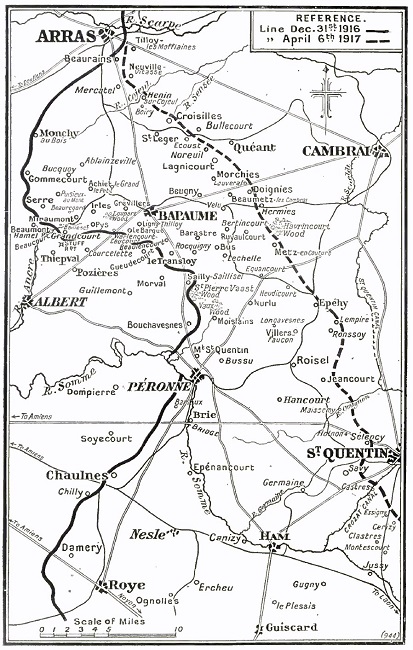

The German withdrawal to

the Siegfried

Position, indicated by the dashed line (Wikimedia Commons)

In 1918 the trench deadlock on the

Western Front was finally broken, first by by the German

Army's new tactics (the hurricane artillery bombardment,

specially trained assault troops, combined-armed battle

groups), then by the Allies’ employment of the

tank on a

large scale against an exhausted enemy. In both cases, the

effect was to restore tactical battlefield mobility. But

though a few visionary military thinkers perceived that

those final battles heralded another revolution in the art

of war, the memory of the Western Front’s blood-soaked,

trench-scarred battlefields remained dominant in the minds

of soldiers, politicians and the European peoples for the

next twenty years. One of them was a German soldier who’d

served in the trenches for four years, and who on Armistice

Day was lying in a military hospital, having been blinded by

mustard gas. His name was Adolf Hitler.

Adolf Hitler (right) and

comrades of the 16th Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment,

circa 1916 (Bundesarchiv)