● ● ●

Note on Comparative

Naval Ranks

Though flag officers’ rank

titles varied from navy to navy, their overall rank

structures were similar. The Royal Navy’s flag ranks were

Admiral of the Fleet, Admiral, Vice-Admiral, Rear-Admiral

and Commodore—the last entitled to fly the so-called broad

pennant instead of a rank flag. In the German Navy the ranks

were Grand Admiral (Großadmiral), Admiral (Admiral),

Vice-Admiral (Vizeadmiral) and Rear-Admiral (Konteradmiral).

Commodore (Kommodore) in the German Navy was not a

rank but an appointment—typically of a Captain (Kapitän

zur See) appointed to command a flotilla or group of

ships. While holding such an appointment he was authorized

to use the title Kommodore and to fly a broad

pennant.

● ● ●

One of the most consequential

decisions of the Great War was taken by Winston Churchill,

First Lord of the Admiralty, on 2 August 1914.

Coincidentally with the Balkan crisis sparked by the

assassination of the Austro-Hungarian heir, Archduke Franz

Ferdinand, the Admiralty had been conducting a test

mobilization of the Royal Navy. This involved the recall of

naval reservists to man ships in caretaker status, followed

by the concentration of the fleet at its war stations in

home waters. Anticipating that Britain would likely be drawn

into the war just beginning, the First Sea Lord, Admiral

Prince Louis of Battenburg, ordered the Fleet’s scheduled

demobilization to be delayed. Churchill, reaching the

Admiralty from his country home some hours later, confirmed

Battenburg’s order. Thus when Britain did declare war on

Germany (4 August), the Fleet was ready.

As with land warfare, modernity and

the Industrial Revolution had revolutionized the naval scene

between 1815 and 1914. The Royal Navy of the Napoleonic era,

wooden-walled, sail-propelled, armed with short-range

smoothbore cannon, was but a memory. Now steam, iron and

steel, high explosives and long-range gunnery were dominant,

embodied above all in the dreadnought battleship, which may

well be said to have represented the pinnacle of military

technology in 1914.

This class of warships took its

name from the first of the breed: HMS Dreadnought,

which was entered service with the Royal Navy in 1906.

Dreadnought represented a revolutionary break with past practice.

By the late nineteenth century battleship design had settled

into a standard pattern. The typical battleship, circa 1900,

displaced about 15,000 tons, had a maximum speed of about 18

knots, was propelled by reciprocating steam engines, and was

armed with four guns of 12-inch caliber. These main battery

guns were supplemented by a secondary battery of some dozen

5- or 6-inch guns plus smaller quick-firing guns for defense

against torpedo boats. Many such battleships were

additionally armed with torpedo tubes. The maximum effective

range of the big guns was about 10,000 yards, though

anticipated battle ranges were much shorter: 5,000 yards at

most. The last British battleships of this type, the six

ships of the “Duncan” class, were commissioned in the Royal

Navy as late as 1903-04.

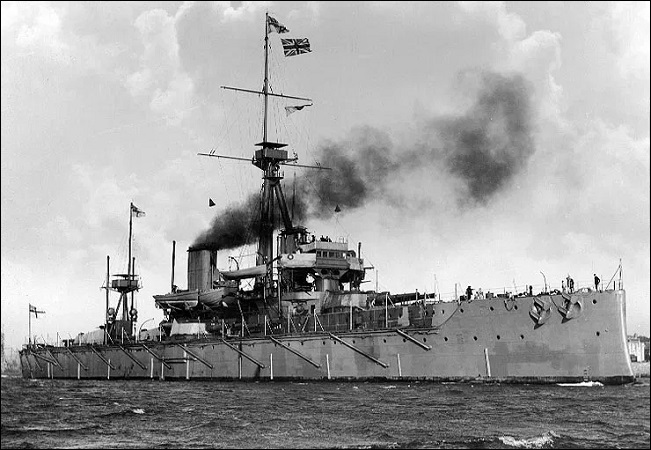

A typical battleship, circa 1900: the

Imperial Russian Navy's Slava. On a displacement of

13,500 tons she carried an armament of 4 x 12in guns and 12

x 6in guns in turrets, plus 20 x 3in guns in hull positions and a pair

of submerged torpedo tubes. Her best speed was 18 knots.

(Imperial War Museum)

But even as the “Duncans” entered

service, there was growing concern among senior British

naval officers that their battleships lacked sufficient

firepower. The latest foreign battleships were being armed

with an intermediate battery of 8in guns in addition to

their 12in and 5- or 6in batteries. An example was the Japanerse

“Kurama” class, armed with 4 x 12in and 8 x 8in guns. Britain's reply was

the “King Edward VII” class (eight units), laid down in 1902 and

commissioned in 1905-07. These handsome ships displaced some

1,000 tons more than the “Duncans” and were armed with four

12in, four 9.2in and ten 6in guns. The 9.2in gun was a

powerful weapon that nearly doubled the ships’ firepower—on

paper. But this mixed main armament turned out to embody a

serious flaw. Naval gunfire was adjusted by observing shell

splashes and correcting the firing data accordingly.

Unfortunately, it was found that 12in and 9.2in shell splashes were practically impossible to

distinguish from one another at expected battle ranges,

which made mixed-caliber salvo firing difficult if not

impossible.

For some years, however, a much

more revolutionary idea, the “all-big gun” battleship, had

been circulating in naval circles. As envisioned by Admiral

Sir John “Jackie” Fisher, Britain’s reforming First Sea Lord

between 1904 and 1911, the new battleship would carry ten

12in guns, so disposed as to provide an eight-gun

broadside. The only other armament would be some two

dozen 12-pounder (3in) quick-firing guns for defense

against torpedo boats. Fire control would be provided by an

electrical transmission system that automatically converted

data from the ship’s rangefinders into elevation and

deflection settings for transmission to the gunnery

officer’s plotting table and each main battery turret. This

system, called director control, extended the main battery’s

maximum effective range to more than 15,000 yards. The

ship’s standard displacement would be over 18,000 tons; its

four-shaft steam turbine engines would give a maximum speed

of 21 knots. Protection consisted of an armored belt with a

maximum thickness of eleven inches plus twelve-inch armor for the

conning tower and the main battery turrets.

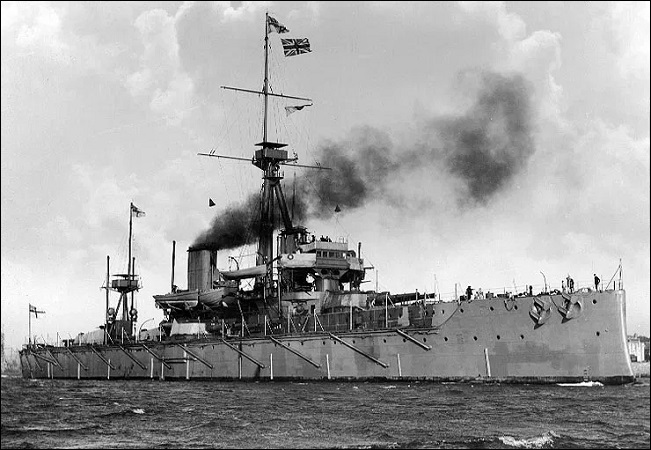

HMS Dreadnought as she appeared

before the war (Imperial War Museum)

There were critics of the new

design, particularly regarding its puny secondary armament,

but Fisher with his typical energy and intemperance trampled

them down. The construction of HMS Dreadnought

commenced in October 1905 and she was commissioned for

service in December 1906—instantly rendering every other

battleship in the world obsolete.

The fallout from Dreadnought’s

appearance was geopolitical as well as tactical and

technical. In Germany the advocates of Weltmacht—

world power—had long been agitating for the creation of a

first-class navy. At the end of the nineteenth century the

possession of overseas colonies and a powerful battle fleet were

held to be prominent among the attributes of a great power.

Germany, it was said, was entitled to its “place in the sun”

alongside Britain, France, Russia and the United States.

Colonies, overseas trade and a navy to defend them—these

would secure for Germany the global power to which she was

entitled.

For a long time, however, the

presence of Otto von Bismarck at the head of the Kaiser’s

government stymied such ambitions. Having engineered the

country’s unification in 1871 the Iron Chancellor declared

Germany to be a “satiated power,” and his foremost concern

was continental diplomacy. United Germany, he said, needed

time to knit together its new imperial institutions.

Bismarck was particularly concerned to prevent another war.

To that end he labored long and assiduously to ensure that

France, defeated and humiliated in the war of 1870-71, could

not acquire a powerful ally for a war of revenge. The most

logical candidate for the position was Russia, which had

grievances of its own. So his diplomatic priority was the

maintenance of good relations with Russia—this despite the

rivalry between the latter and Austria-Hungary over the

Balkans and the Near East. It was a delicate balancing act

and Bismarck thought that Germany’s acquisition of colonies

and a big navy would only disturb that balance. He wanted no

squabbles with Russia, France, Britain or anybody else over

colonial issues. Asked in the mid-1880s about his preferred

map of Africa he replied: “Here is France on one side, here

is Russia on the other side, and here is Germany in the

middle. That is my map of Africa.”

Only grudgingly did Bismarck permit

the acquisition of German colonies in Africa and the

Pacific. He did so as a political concession to the

Weltmacht faction and showed little interest in colonies

thereafter—even proposing at one point to sell German

Southwest Africa to Britain. But with his dismissal by

Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1890 Bismarck’s foot on the imperialist

brake pedal was removed. Public opinion came strongly to

favor an active colonial policy and, in particular, the

construction of a powerful navy.

Kaiser Wilhelm II in naval uniform (Wikimedia

Commons)

After 1815 the Kingdom of Prussia

had set about creating a navy of modest size to defend its

Baltic and North Sea coasts, and to show the flag around the

world. The Prussian fleet became the navy of the North

German Confederation in 1867 and of the Imperial German Navy

(Kaiserliche Marine) in

1871. Even so in Bismarck’s time it remained a small force,

decidedly secondary in importance to the Army. But all this

changed after 1888 when a new Kaiser ascended the throne.

Wilhelm II was a naval enthusiast who both admired and

envied Britain’s incomparably powerful Royal Navy. His dream

of a German fleet equal to Britain’s harmonized with public

opinion, though there were many in the political class who

opposed the idea, arguing that more money and manpower for

the Navy meant less money and manpower for the much more

important Army. Therefore the Kaiser proceeded cautiously.

In 1889 he reorganized the naval command structure, creating

an Imperial Naval Office (Reichsmarineamt)

responsible for planning and supervising naval

construction, maintenance and procurement, and advising the

Reichstag (imperial parliament) on naval issues. And

slowly, the fleet began to grow, Germany’s first seagoing

battleships being constructed and commissioned in 1890-94.

Grand Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz,

architect of the Imperial German Navy (Wikimedia Commons)

The year 1897 was decisive for the

Navy—and, as it proved, for Germany, Europe and the world. A

dispute over the naval budget had led to the resignation of

the State Secretary of the Reichsmarineamt and the

post was offered to Rear-Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz. It was

he more than any other man who transformed the

Kaiserliche Marine

into a world-class navy—posing a threat that Britain, the

world’s preminent naval power, could not ignore.

Shortly after

his appointment Tirpitz submitted his First Naval Bill to

the Reichstag.

It envisioned the construction of a battle fleet of two

squadrons, each with eight

battleships, plus a fleet flagship and two reserve ships.

This program, costing 408 million marks, was to be completed

by 1905. Hitherto the Navy had grown piecemeal; now growth

would proceed on the basis of a seven-year program. The

annual cost—58 million marks—was not much more than the

existing naval budget and though objections were again raised

about funding the Navy at the expense of the Army, the bill

was eventually passed with a comfortable majority. A Second

Naval Bill followed in 1900, this one providing for a fleet

totaling 38 battleships, the program to be completed in

1920.

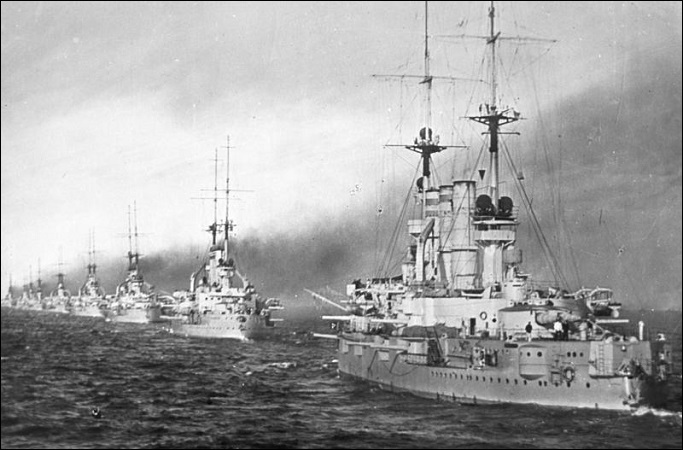

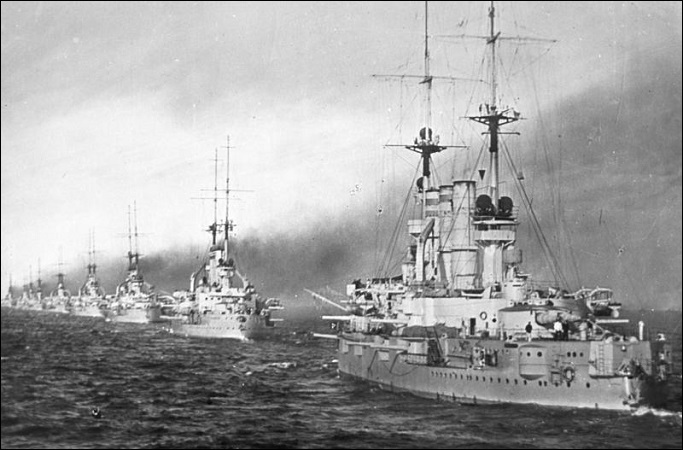

Battleships of Germany's High Seas Fleet,

circa 1910 (Bundesarchiv)

Tirpitz proved

adept at public relations. He established a press bureau in

the Reichsmarineamt

that provided briefings and even pre-written articles for

the convenience of journalists. Speakers were recruited from

business and academic circles to promote the bill,

explaining its necessity for Germany and its benefits for

trade and industry. Tirpitz also sponsored the formation of

the German Naval League (Deutscher Flottenverein)

an interest group favoring a strong navy that did much to

popularize the cause. And he took great pains to cultivate

support in the Reichstag,

patiently and

good-humoredly lobbying its members, answering their

questions and meeting their objections.

Though never

mentioned by name, Britain was the clear target of Tirpitz’s naval program.

Scant notice was taken in

Britain of the First Naval Bill,

but

the passage of the Second

Naval Bill seriously alarmed the Admiralty: The eight “King

Edward VII”-class battleships, ordered in 1902, were

intended as a reply to the German challenge. And the

appearance of HMS Dreadnought

in 1906 gave a tremendous boost to Germany’s burgeoning

naval ambitions. By rendering existing battleships obsolete,

the all-big gun design appeared to give the

Kaiserliche Marine a

real chance to achieve parity with Britain. The ensuing

Anglo-German naval arms race and its diplomatic fallout were

majors factor in the

deterioration of relations between the two countries in the

decade preceding the outbreak

of the Great War.