● ● ●

The strategic imperatives governing

the Great War at sea were embodied in the central standoff

between Britain’s Royal Navy and Germany’s Kaiserliche

Marine.

For

Britain, a globe-spanning imperial power heavily dependent

on imports to feed both industry and population, freedom of

the seas was the sine qua non of victory; naval supremacy

was its guarantee. These considerations governed the Royal

Navy’s operations throughout the war. They explain why the

hoped-for clash between the main battle fleets didn’t happen

until May of 1916 and why, when it did, the outcome seemed

indecisive.

When war

broke out in 1914, both the Royal Navy’s leaders and the

British people as a whole looked forward to an early fleet

action in the North Sea: a super-Trafalgar. But the man

newly appointed to command the Grand Fleet (as the Home

Fleet was renamed when war came) took a sober, more

realistic view. Admiral Sir John Jellicoe was a protégé of

Jackie Fisher, the reforming First Sea Lord between

1904 and 1910 (and soon to be reappointed

to that post). In August 1914 he was serving as Second

Sea Lord,

responsible for manning, mobilization,

and other personnel matters.

The First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill,

selected him to replace the incumbent commander of the Home

Fleet, who was verging on retirement: Churchill felt that a

younger, more dynamic commander was needed. His decision

caused much controversy for the incumbent, Admiral Sir

George Callaghan, was greatly admired. Even Jellicoe

protested to the First Lord over Callaghan’s replacement—to

no avail.

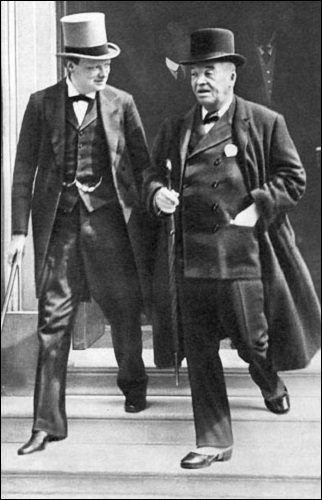

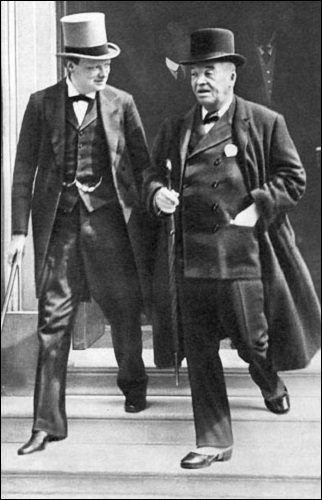

Left: Winston Churchill

and Jackie Fisher. Right: Admiral Sir John Jellicoe

(Imperial War Museum)

John Jellicoe himself was

universally regarded as one of the ablest men in the RN; his

appointment to command the Grand Fleet was a sound move on

Churchill’s part. And it was a fortunate one for Britain

because Jellicoe, despite his natural desire to bring the

German High Seas Fleet (Hochseeflotte)

to battle, was acutely sensible of the risks involved. He

knew that his first, overriding priority as commander of

Britain’s principal naval force was to preserve its power.

As long as the Grand Fleet remained in being, dominating the

North Sea and bottling up the German fleet, the freedom of

the seas would rest with Britain and its allies. And more:

The Grand Fleet’s domination of the North Sea would

automatically impose blockade on Germany and its

allies—strangling their overseas trade and cutting off their

access to foreign sources of raw materials.

Cockpit of the naval war:

the North Sea (Department of History, USMA West Point)

As a glance at the map

shows, in the face-off between the Grand Fleet and the

Hochseeflotte

geography favored the former. Great Britain lay astride

Germany’s routes out of the North Sea, into the Atlantic.

The English Channel was impassible to German shipping and

the northern passages between the Orkney and Shetland

Islands could easily be closed by minefield and patrols. The

Grand Fleet’s war station was at Scapa Flow in the Orkney

Islands. Its presence there, and its frequent sorties into

the North Sea, gave security to the patrols that enforced

the blockade.

In short,

the Grand Fleet’s mere existence secured the basic

objectives of British naval strategy—a fact of which Admiral

Jellicoe was only too well aware.

Battleship HMS Iron

Duke, flagship of the Grand Fleet 1914-17

(Naval

Encyclopedia)

In August 1914 the Royal

Navy in home waters outnumbered the Kaiserliche

Marine by twenty-one

dreadnought battleships plus four battlecruisers to fourteen

dreadnought battleships and five battlecruisers. The RN soon

acquired three additional dreadnoughts: two built in Britain

for the Ottoman Empire, seized in August 1914, and one built

for Chile, purchased later in the year. Both navies had

additional battleships and battlecruisers under

construction, but work was slowed or stopped on all but

those that were close to completion. Initially both fleets

included some pre-dreadnought battleships but these were

quite outclassed by the dreadnoughts and most of them were

soon relegated to secondary duties.

Jellicoe’s overriding concern was to preserve the Grand

Fleet’s initial margin of superiority and he worried constantly that

some mishap—battleships torpedoed by submarines, or sunk in

a minefield, or caught unsupported by a superior German

force—might pare down that margin. These anxieties governed

his conduct of operations in the North Sea from the

beginning of the war to May 1916, when the two battle fleets

finally clashed at Jutland. In August 1914 he carefully

explained to Churchill the dangers of a too-aggressive

policy. The obvious German strategy would be gradually to

even the odds by sinking a ship here and a ship there.

Therefore, said Jellicoe, he would “decline to be drawn”

into a possible submarine ambush or onto a suspected

minefield. Churchill, despite his passionate desire to bring

off a decisive fleet engagement, accepted this reasoning. At

all costs, the Grand Fleet must remain in being.

And in fact, German naval

strategy at the beginning of the war envisioned just such a

gradual evening of the odds: Early operations in the North

Sea were intended to provoke a reaction from the British,

presenting opportunities for isolating and destroying some

portion of the Grand Fleet. To do this it would be necessary

to bring the whole Hochseeflotte

into contact with some part

of the Grand Fleet. To that end, the former’s First Scouting

Group with its high-speed battlecruisers conducted a number

of bombardments of British North Sea coastal towns in late

1914 and early 1915. The idea was to lure out the Grand Fleet’s Battlecruiser Squadron, which would then be engaged by the

Hochseeflotte,

lurking just over the horizon. But the desired ambush never

came off, thanks to the fog of war and uncertainty that

obscured naval operations at a time when radar did not exist

and air reconnaissance was in its infancy.

Battleship

Friedrich der Gross,

flagship of the

Hochseeflotte

1912-17 (Bundesarchiv)

Elsewhere, in the Mediterranean, the Pacific and the South

Atlantic, the early days of the naval war witnessed many

dramatic incidents, including a stinging

defeat for the Royal Navy, albeit one that was soon avenged.

But at sea as on land, the bedrock strategic imperatives of

those early days set up the pattern of the Great War.