● ● ●

On 22 June 1941—the first day day

of World War II for the USSR—the country’s highest military

organ was the Defense Committee of the Council of People’s

Commissars. Immediately under the Defense Committee were the

People’s Commissariat of Defense (for the Army) and the

People’s Commissariat of the Navy. Within the Defense

Commissariat, the principal decision-making body was the

Main Military Council. Command of the Red Army rested with

the People's Commissar of Defense, whose executive agent was

the Chief of the General Staff. Stalin himself, who in May

1941 had assumed the position of chairman of the Council of

People’s Commissars (prime minister) had not yet established

a formal relationship with the armed forces. In the field,

the highest-ranking commands were the sixteen Military

Districts into which the USSR was divided, plus the Far

Eastern Front (army group).

In the event of war, it was

intended to create a war cabinet to direct policy and

strategy at the highest level, and a supreme military

headquarters to plan and direct military operations. Neither

of these bodies existed on 22 June 1941, however. The war

plan also envisioned the conversion of the five western

military districts into operational front (army group)

commands.

The military command structure was

paralleled by the military commissar system, whose task was

to exercise political oversight and control of the Army. The

commissar system had originated during the Civil War and

after being abolished for a time it was reinstituted in

1937, during the military purge that decimated the officer

corps. By 1941 the military commissars, now called deputy

commanders for political affairs, were ubiquitous, being

assigned down to the regimental level. In July 1941 these

political officers were given formal authority to review and

revoke commanders’ orders, and in addition so-called

political leadership officers were assigned down to the

platoon level. At high levels of command political officers

were usually senior party officials. Nikita Khrushchev, for

example, served on the Military Council of Stalingrad Front

as the Party’s representative. Perforce, commanders had to

be granted more latitude in the conduct of operations in

wartime, but political supervision of the Red Army remained

a priority for Stalin and his cronies. The whole system was

run by Main Political Administration of the Army,

responsible for the political supervision of every commander

and the political indoctrination of the troops. The

commissar system was supplemented by the all-powerful

political police, the NKVD, which maintained a Special

Section for Military Affairs.

On 23 June 1941 the Main Military

Council became the Stavka (general headquarters) of the High

Command. Its principal members were Marshal of the Soviet

Union S.K. Timoshenko (Chairman), Marshal of the Soviet

Union K.Y. Voroshilov (Chairman of the Defense Committee)

General of Army G.K. Zhukov (Chief of the General Staff),

Fleet Admiral N.K. Kuznetsov (People’s Commissar of the

Navy), Marshal of the Soviet Union Semyon Budyonny, V.M.

Molotov and Stalin (members). In July, when Stalin assumed

the title of Supreme Commander (Generalissimus), it

became the Stavka of the Supreme Command, and in August it

was retitled the Stavka of the Supreme High Command, with

authority over all the armed forces of the state. Within

Stavka the General Staff of the Red Army was the main

military planning agency. The General Staff was also

responsible for doctrinal matters: the organization of

military formations and their tactical/operational

employment.

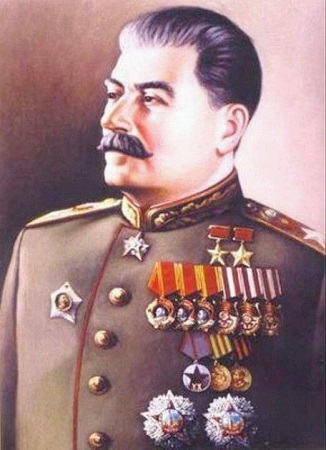

The Generalissimus:

Stalin as Supreme Commander. An idealized portrait by a

Soviet artist.

On 30 June 1941, Stalin established

the State Defense Committee (GKO), with himself as chairman.

The GKO had supreme authority over all political, economic,

and military policy. This centralization of war powers was

in sharp contrast to the situation on the German side, where

competing fiefdoms—the Party, the SS, the armed

forces—engaged in a constant struggle for authority and

resources, greatly to the detriment of the war effort.

It need hardly be said that

whatever the details of Stavka’s organizational template,

the authority of Stalin was paramount. His assumption of the

position of Generalissimus merely formalized a

preexisting situation. Early in the war his influence on

military matters was frequently counterproductive—as when he

refused to sanction the timely abandonment of Kiev in

September 1941, a mistake that led to the loss of some

700,000 men. But unlike Hitler, Stalin learned from his

mistakes and on the whole he proved to be a far more

effective supreme commander than the German leader.

During most of the war the highest

level of command in the field was the front (army group).

Fronts were quite variable in size, ranging from three

armies to as many as nine. In 1943 infantry armies typically

embodied between six and twelve rifle

divisions; the average was

eight. If earmarked to participate in a major offensive, an

army was heavily reinforced with tank, artillery, rocket

artillery and self-propelled artillery (armored assault gun)

units. Sometimes a full

tank corps was attached. Shock

armies were similar to infantry armies but with more

artillery and a higher level of mechanization. Tank armies

usually had two tank corps and a mechanized corps and they

too were reinforced with additional units as required.

Generally, Red Army units were smaller than German or

Western Allied ones with the same designations. Tank

brigades were really battalions, tank and mechanized corps

were really divisions, the chronically understrength rifle

divisions were usually the size of brigades. Until late in

the war the Soviet front was smaller than the German army

group, two or three of the former, usually, being equivalent

to one of the latter.

Marshal of the Soviet

Union G.K. Zhukov officiates at the formal surrender of

Germany, Berlin, 9 May 1945 (Red Army)

Major operations involving more

than one front were coordinated on Stalin’s behalf by Stavka

representatives, Zhukov often serving as such. This was an

informal arrangement but it worked well once Stalin learned

to listen to his senior military commanders—this in sharp

contrast to the situation on the German side, where Hitler’s

longstanding distrust of his generals gradually developed

into a mania. To be sure, the war opened disastrously for

the USSR and many unsuccessful commanders found themselves

facing an NKVD firing squad. But eventually there was

developed a body of competent, war-experienced senior

officers, and though it would be going too far to say that

Stalin trusted his generals he and they managed to forge an

effective partnership.

The efficiency of its high command

was a major factor in the USSR’s victory over Nazi Germany.

Stavka, and the GKO above it, provided the armed forces in

the field with clear direction, establishing strategic

priorities and allocating resources in a manner that the

enemy’s fragmented command structure could not match.

● ● ●