● ● ●

NOTE ON NOMENCLATURE

The following abbreviations are used in

this article: AA (antiaircraft), A/S (antisubmarine), DC

(depth charge), FAA (Fleet Air Arm), HA (high-angle

antiaircraft gun), HMS (His Majesty's Ship), MG (machine

gun), RAF (Royal Air Force), RN (Royal Navy), TT (torpedo

tubes).

● ● ●

On the eve of war in 1939, Britannia no

longer ruled the waves, as she had twenty-five years earlier

at the beginning of World War I. The costs of that war, the

subsequent financial crisis, economic stagnation, and a

national malaise compounded of exhaustion and

disillusionment combined to impose limits on the size and

power of the Royal Navy (RN). That despite such constraints

the RN performed as well as it did in 1939-45 is a tribute

to the traditions and fighting spirit of the Senior

Service—virtues preserved intact despite the troubles of the

interwar period.

In the immediate aftermath of the World

War I the government of the day, convinced that Britain

could no longer win a naval arms race, participated in the

negotiations that led to the Washington Naval Treaty (1921).

The world’s major naval powers agreed to limit the size of

their navies by specifying maximum tonnages for capital

ships (battleships and battlecruisers), aircraft carriers

and smaller warships, with gun calibers being capped at 16in

for capital ships and 8in for other warships. For the RN,

Britain’s signature on this treaty meant the cancellation of

the revolutionary “G3” battlecruisers, four of which were on

order, and the acceptance of naval parity with the United

States. The size of the battle fleet was fixed at eighteen

battleships and four battlecruisers. Two new battleships,

reduced editions of the “G3” design, were permitted to be

built, and when they entered service four older battleships

were to be retired. The service life of capital ships was

set at twenty years, and no new ones were permitted to be

constructed by any of the signatory powers until 1931.

Battleship HMS Warspite of the "Queen

Elizabeth Class after her 1934-37 reconstruction.

Modifications included a new tower bridge, secondary battery

reduced to 8 x 6in guns, addition of 8 x 4in HA in four twin

mounts and 32 x 2-pounder pompoms in four octuple mounts as

light AA . (Imperial War Museum)

The RN was thus compelled to discard all

of its older capital ships, nineteen of which were

decommissioned and scrapped between 1922 and 1928. A large

number of smaller warships went to the breakers as well and

the interwar fleet, if not quite a shadow of its former

self, was much reduced. But in the circumstances of 1919-22,

the Washington Naval Treaty was a sensible measure. Indeed,

it seems likely that many of its mandated reductions would

have been necessary in any case, given Britain’s parlous

financial condition at the time.

The onset of the Great Depression (1929)

led to another attempt at naval disarmament: the London

Naval Conference of 1930. The British government pressed for

further reductions. Battleships were to be limited to fifteen

apiece for Britain and the US, with nine for Japan. Caps

were also placed on total cruiser and destroyer tonnages.

The agreement required the RN to cut its cruiser force from

70 to 50 ships and discard many older destroyers. But

neither France nor Italy accepted the new agreement and

thanks to the deteriorating international situation,

it was eventually repudiated by all signatories.

The London Naval Conference reflected a

constant preoccupation of successive British governments

between 1919 and 1930: the need to reduce military spending

to an absolute minimum. This need was met by the so-called

Ten Year Rule, first adopted in 1919. Defense planning was

to be based on the assumption that Britain would not be

involved in a major war for the next ten years, with the

term extended each year. So in 1919 it was assumed that

there would be no major war before 1929, in 1920 the

terminal year was advanced to 1930, and so on. This was

convenient for the politicians, but the ten-year assumption,

valid enough in 1919, became more and more dubious with the

passage of time. The Ten-Year Rule was not formally

abandoned until 1932, and then only with many misgivings.

Thus strict budgetary limits were set on

the RN’s ability to profit from the lessons learned between

1914 and 1918. During the war, for example, the RN had

pioneered the development of naval airpower, but

subsequently its

potential could not be exploited to the full. To be sure,

the RN commissioned the world’s first aircraft carrier

designed as such from the keel up: HMS Hermes, laid

down in 1918 and completed in 1924. The soundness of her

basic design is evident from a glance at any photo or

drawing of the ship: She is clearly the direct ancestor of

the aircraft carriers in service today. Hermes

followed the very similar HMS Eagle

into service. That carrier was a conversion of the

incomplete battleship Almirante Cochrane,

which had been under

construction in Britain for the Chilean Navy in 1914. The

outbreak of the war caused her construction to be suspended

and in 1918 she was purchased by the Admiralty for

conversion to an aircraft carrier. Along with HMS

Argus, an earlier

conversion that had entered service in 1918, Eagle

and Hermes

proved very successful in service and survived to fight—and

be sunk—in World War II.

Four

more carriers joined the fleet before the outbreak of World

War II. Three of them were the converted “large light

cruisers” Furious,

Courageous

and Glorious.

The former had actually undergone a makeshift carrier

conversion in 1917 but this proved unsatisfactory and in

1922 she was rebuilt. The other two were converted in

1924-28. As carriers these ships were faster than

Eagle and

Hermes and could carry

more aircraft. Finally there was HMS Ark Royal,

the RN’s second carrier

to be designed as such. She was much better than the other

six, able to carry a larger air group and mounting a

powerful antiaircraft armament. All but Argus

and Furious

were lost during World War II.

Carrier HMS Courageous in 1935

(Imperial War Museum)

But

though the RN had a respectable carrier force by the late

1930s, interservice rivalry conspired with budgetary

restrictions to impair the development of effective naval

combat aircraft. When the Royal Air Force was established as

an independent branch of the armed forces in 1918, it

absorbed the Royal Naval Air Service. Henceforth, though the

RN owned the aircraft carriers, the aircraft themselves and

their aircrew belonged to the RAF. And unfortunately, the

RAF’s leadership had little interest in or commitment to

naval aviation. Senior airmen championed the doctrine of

strategic bombing—which, they claimed, would reduce the Army

and the Navy to auxiliaries of the Air Force. This

unsatisfactory state of affairs was rectified only in May

1939, when control of the RAF’s Fleet Air Arm reverted to

the RN, but by then the damage was done. At the beginning of

World War II the FAA had only twenty squadrons with 232

combat aircraft, numbers insufficient to provide all

existing carriers with effective air groups.

Hermes, for instance,

serving with the Channel Force, had only twelve aircraft

embarked—eight to ten fewer than her maximum complement.

The

aircraft themselves were hardly modern. The principal

fighters were the Sea Gladiator, a navalized version of the

RAF’s last biplane fighter, and the Skua, an underpowered

monoplane two-seater that doubled as a dive bomber. The

torpedo bomber was the Swordfish, a biplane of decidedly

antique appearance that nevertheless served throughout World

War II (and compiled a surprisingly impressive record in a

number of roles).

The "Stringbag," as the Fairey Swordfish

was nicknamed, was the RN's carrier-based torpedo bomber at

the beginning of the war (Imperial War Museum)

The

submarine was another new weapon that had proved itself in

World War I, but aside from a few boats of the wartime “L”

class that were completed in 1919-20, only fifty were built

up to 1939. Thus the RN’s submarine fleet shrank as older

classes were withdrawn from service. The prewar program

followed a policy of gradual improvement, culminating in the

“S,” “T” and “U” classes. These submarines, built between

1934 and 1939, were repeated with improvements for the much

larger wartime construction program.

World War

I had shown the need for small A/S escorts along the lines

of the “Flower” class fleet sweeping sloops of World War

I—some of which were retained in the postwar fleet—but once

again budget constraints prevented much from being done. No

new escort sloops appeared until 1928 and by 1939

thirty-five had been built. This modest program was

justified on the grounds that such ships were useful for

peacetime colonial service, but they were designed with the

wartime escort mission in mind. Several of the new sloops

were allotted to the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) and the Royal

Indian Navy. As with submarines, the last sloops built

prewar were repeated with improvements in the wartime

building program. Many destroyers were fitted with DC racks

and throwers as well as Asdic (sonar), but unfortunately the

various A/S mortars used in World War I were not further

developed.

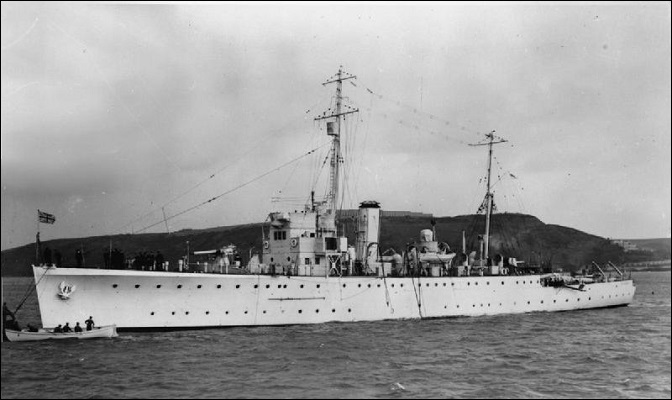

HMS Penzance, one of the four

sloops of the "Hastings" class, was commissioned in 1931 and

served as an escort in World War II (Imperial War Museum)

After

the two reduced “G3” ships (Nelson

and Rodney)

entered service in 1927, no new battleships joined the RN

before the outbreak of World War II. In 1932 the battle

force consisted of those two ships, five of the “Queen

Elizabeth” class, five of the “Royal Sovereign” class and

three battlecruisers: fifteen in total. The thirteen older

ships were all modernized to some extent, for instance

receiving a more-up-to-date antiaircraft (AA) armament.

Of the 56

cruisers extant in 1919, about half were disposed of between

1926 and 1935. Only the later “C” class, the “Hawkins”

class, the “D” class and the “E” class survived to fight in

World War II. Several of the “C” class were refitted as AA

escorts with an armament of 4in HA guns, but otherwise the

older cruisers were little altered. Fifteen heavy cruisers

armed with 8in guns were built between 1926 and 1931; their

general design and armament conformed to the restrictions

laid down by the Washington Naval Treaty. They were followed

by twenty-two light cruisers, armed with 6in guns, built

between 1931 and 1939. Two of the heavy cruisers and three

of the light cruisers were allotted to the RAN.

Light cruiser HMS Dispatch off the

Panama Canal Zone in 1939 (US Navy Heritage and History

Command)

It was

much the same story with destroyers. The oldest of them were

disposed of immediately after World War I, and most of the

others were gradually retired between 1926 and 1938. By 1939

only some of the “S” and “V & W” classes remained, around 35

ships in total. Destroyer production resumed in 1926 and

accelerated after 1932 but even so numbers remained

insufficient. As with cruisers, a number of destroyers, old

and new, went to the RAN. The interwar destroyers mostly had

a main armament of 4 x 4.7in guns and 8 or 10 x TT in

quadruple or quintuple mounts.

A major

weak spot for the RN was in the area of AA defense. As

constructed, most of the interwar cruisers had only 4 x 4in

HA guns. Close-range AA weapons were the 2-pounder (40mm)

pom-pom in single, quadruple and octuple mounts and the

caliber .50 AA MG in a quadruple mount. The former had

adequate if not particularly impressive performance, but the

latter was practically useless. As built, many of the

interwar destroyers had only a pair of quad .50 AA MG; their

4.7in guns had insufficient elevation to be effective in the

AA role.

Though by

1935 the necessity of naval rearmament was recognized by the

British government, it nevertheless proceeded at a glacial

pace. The 1936-37 building program included two battleships,

two aircraft carriers, seven cruisers, eighteen destroyers,

eight submarines and ten smaller ships. Few of the larger

ships would enter service before 1939-41, however, so that

the RN would face the test of war with barely adequate

numbers and some critical material deficiencies.

(For

additional information on RN warship classes of World War I,

see Warships of

the Great War Part One and

Warships of the Great War Part Two.)

● ● ●