|

● ● ●

Since the seventeenth century a

special bond had existed between the monarch and the officer

corps of the Prussian and later the German Army. It was that

Army, founded by the Great Elector, that bound the

heterogeneous lands of the Hohenzollerns together, and in

the fullness of time made Prussia possible. Frederick

William I and Frederick the Great habitually wore officer's uniform, thus making it a mark of

prestige and honor, reserved for the Prussian nobility—the Junker

class. Those officers gave

their oath to the King—after 1871 to the King-Emperor—personally. It

was an ancient relationship, founded in the days of the pike

and the matchlock musket, that still stood firm at the dawn

of the twentieth century.

The Army’s corporate identity was embodied

above all in the Great General Staff (Großgeneralstab) an

institution that traced its origins to the Great Elector's reign and

assumed its modern form between the Napoleonic wars and the

unification of Germany in 1870-71. The Army’s central role in these

patriotic epics increased its prestige still further, and the Great

General Staff under Field Marshal Helmuth Graf von Moltke received

much of the credit for the three victorious wars that set the seal

on German unification. In the decades leading up to the First World

War, the Great General Staff was Germany’s de facto supreme command

and highest military planning entity, its authority underscored by

the Chief of Staff’s right of immediate access to the Kaiser, the

titular supreme commander.

Defeat in the First World War, did not, as

might be supposed, fatally undermine the reputation of either the

Army or its General Staff. The latter, indeed, was abolished by the

terms of the 1919 Peace Treaty, but its spirit lived on in the

100,000-man Reichswehr, the

vestigial army permitted to Germany by the victorious powers. And

the reputation of the Army as a whole was shielded by the legend of

the “stab in the back”: the claim that the soldiers at the front had

been betrayed by the treasonous “November criminals” of 1918.

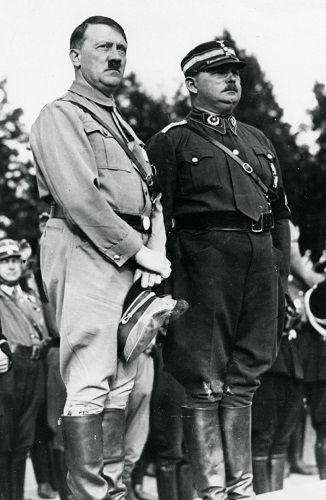

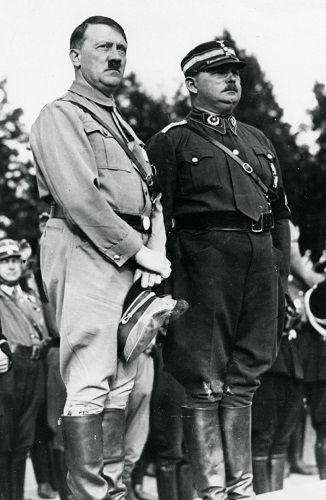

Hitler with SA leader

Ernst

Röhm. The Führer

purged his old comrade at the Army's

behest (Bundesarchiv)

Hitler’s ascent to power in January 1933

was greeted by the Army's leaders with mixed emotions. Of course

they heartily approved of his proclaimed foreign

policy goals: rearmament and the restoration of Germany’s great

power status. But they deeply disapproved of and viewed with alarm

the Party’s brown-shirted Stormtroopers (Sturmabteilung

or SA). Ernst Röhm, the SA‘s leader, aspired to make his

organization the “people’s army” of

National Socialist Germany, absorbing the Reichswehr

in the process.

To this the generals were adamantly opposed and the pressure they

brought to bear was largely responsible for Hitler’s

decision to purge the SA in 1934, killing off Röhm and his

associates in “the

Night of the Long Knives.” The alliance

between the Nazi Party and the Army against the SA was

formalized in the Deutschland Pact (June 1934), so

called because it was agreed to by Hitler and the Minister

of Defense, Colonel-General Werner von Blomberg on board the

Navy's new armored cruiser. The SA purge was launched soon after

their meeting. The fact that among its victims

were General

Kurt von Schleicher, who’d served briefly

as chancellor before Hitler’s appointment, and his former

aide, General Ferdinand von Bredow, was indeed disturbing to

the Generalität. But the Army-Nazi alliance

remained intact.

The elimination of the

SA threat was followed by Hitler’s proclamation of German

rearmament in March 1935—which included the reestablishment of the Great

General Staff in the form of the Army High Command (Oberkommando

des Heeres or OKH) Though he deeply distrusted the Army’s

leaders, the Führer realized that he needed their professional

expertise to rebuild German military power. For their part the

generals were delighted, and they confidently expected to be recognized once more as first

among equals in the German military establishment.

The reorganization

following the rearmament proclamation established a Ministry of War

and commanders-in-chief for the three branches of the armed forces (Wehrmacht):

Army (Heer), Navy (Kriegsmarine) and the new Air Force

(Luftwaffe). As head of state Hitler was supreme commander

but the functional commander-in-chief of the Wehrmacht was

Blomberg, now a field marshal, as Reich Minister of War.

But though he was a brother officer, Blomberg was viewed with suspicion

by the Army’s leaders. They feared he would exploit his position to

create an armed forces high command organization, usurping the

Army’s traditional authority as embodied in the OKH. The Generalität

also disliked Blomberg's excessive deference to

Hitler. On his own initiative the Minister of War purged

Jews from the ranks of the armed forces, added Nazi symbols

to military uniforms and flags, and altered the military

oath of allegiance in such a way as to make it an oath of

obedience to the Führer personally.

Field Marshal Werner von Blomberg

(Photo: Bundesarchiv)

In 1934, General of Artillery Werner

Freiherr von Fritsch had been appointed Chief of the Army Command,

and he was promoted to colonel-general and made Commander-in-Chief

of the Army when that office was established in 1935. Fritsch was a

deep-dyed conservative with anti-Semitic views who thoroughly

approved of Hitler’s general foreign policy. But he was also much

admired in the officer corps for his professionalism and

determination to uphold the Army’s status. Fritsch was seconded by

the Chief of the General Staff, General Ludwig Beck. He too was

generally supportive of Nazi goals but gradually became alarmed

over what he regarded as Hitler’s high-risk foreign policy.

Another key figure was General of Infantry

Gerd von Rundstedt, the senior officer of the Army by years of

service, who in 1934 was commanding

Reichswehr-Gruppenkommando 1

in Berlin, the higher military headquarters for eastern Germany. As

the doyen of the officer corps

Rundstedt wielded considerable influence.

In 1934, when the anti-Nazi General Kurt

Freiherr von Hammerstein-Equord resigned

as Chief of the Army Command, Hitler proposed to replace him with

General Walther

von Reichenau.

But Reichenau's pronounced pro-Nazi views made him unacceptable to the officer

corps and Rundstedt led a group of senior officers in opposition to

his appointment. Hitler thereupon backed down, appointing Fritsch

instead.

For strictly practical reasons, the senior leadership of the Army advocated a cautious approach to rearmament and foreign

policy. To men like Fritsch, Beck and Rundstedt it

was clear that many years must elapse before Germany would be ready

for war. The rapid expansion of the Army—in the first instance from

ten to thirty-six divisions—seemed to them over-hasty. The Generalität

was also disquieted by Hitler’s increasingly bellicose behavior on the

international stage, which they feared would precipitate Germany

into a war for which country was in no way prepared. Their increasingly

pointed objections to all this alienated Hitler—who soon hit upon

a pretext for getting rid of them and all such skeptics in uniform.

Fritsch and Beck observing Army

maneuvers, 1937 (Photo: Bundesarchiv)

In January 1938 the War Minister, Blomberg,

who was a widower, married a much younger woman of humble

background. This match initially met with Hitler’s approval as a

counterblast against what he viewed as the aristocratic snobbery

that permeated the higher ranks of the Army. The Führer even agreed to stand as witness to the marriage. But it was

soon discovered that the bride had a long criminal record as a

prostitute and had even

posed for pornographic photos. Embarrassed and enraged,

Hitler demanded and received the Field Marshal's resignation.

Probably he was not sorry to do so: The Führer had neither

forgotten nor forgiven the high-handed manner in which

Blomberg had delivered the Army's ultimatum regarding the

SA.

The Army's leaders regarded Blomberg’s

fall from power with equanimity. But the sequel dismayed them: Fritsch,

the Army Commander-in-Chief, was slapped with an accusation of

homosexual misconduct. In reality this charge was false, the result

of an intrigue by Heinrich Himmler, the SS chief, and Hermann Göring,

the commander of the Luftwaffe. The former wished to

undermine the authority of the Army leadership so as to promote the

interests of his own SS organization, while the latter wished to

prevent Fritsch from replacing Blomberg, and thereby becoming his,

Göring’s, superior.

Fritsch protested his innocence—even going

so far as to challenge Himmler to a duel—to no avail. He too was

forced to resign, being replaced by Colonel-General Walther von Brauchitsch. The Army’s senior officers were appalled and demanded a

military “court of honor” to investigate the case. This was granted

and the court exonerated Fritsch in full of the charges against him.

But Hitler refused to restore him to command of the Army, arguing

that a replacement had already taken over. Fritsch was fobbed off

with an appointment as honorary colonel-in-chief of his old

regiment, and consigned to the retired list.

Hitler exploited the

Blomberg-Fritsch

Affair to cement his personal control over the armed forces. No

replacement was named for the disgraced Minister of War. Instead the Führer took over

personally, and the War Ministry became the High Command of the

Armed Forces (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht or OKW). Its chief

was General Wilhelm Keitel, a man on whom Hitler could rely to do as

he was told. Beck, the Army Chief of Staff, resigned shortly

afterward, being replaced by General Franz Halder.

For the moment the OKH was able to preserve

some degree of independence. But inevitably its new rival, the OKW, would aspire to a

superior role, and as Hitler’s personal military headquarters and

planning staff it posed a real threat to the Army's position. Moreover, the logic of the Nazi

leadership principle (Führerprinzp) cut

against all claims of institutional autonomy: the Führer alone could

decide and decree. And this progressive centralization of

power was to be accelerated by the pressures and crises of the war

now impending. Month by month, year by year, the proud German Army

would watch helplessly as its independence withered away.

● ● ●

Copyright © 2020 by Thomas M. Gregg. All Rights

Reserved

BACK to

WAR ROOM Front Page

|