● ● ●

The prelude to Operation

Barbarossa—the invasion of the USSR—erased such independence as the High Command of the Army (Oberkommando

des Heeres or OKH) still possessed. In his capacity as

supreme commander of the armed forces, Hitler decreed that

henceforth OKH would concern itself with the Russian front

exclusively. All other areas of operations were designated

as OKW (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht or High Command of

the Armed Forces) theaters of war. Thus unity of command, to

the extent that it could still be said to exist, was

embodied in Hitler’s person alone. The authority of the

Commander-in-Chief of the Army, Field Marshal Walther von

Brauchitsch, was circumscribed accordingly: He could no

longer issue orders to Army commands in the OKW theaters.

Hitler also took an

active hand in the planning of Barbarossa. He, von Brauchitsch

and the Chief of the General Staff, Colonel-General Franz

Halder, agreed that the first objective must be the

encirclement and destruction of the Soviet forces in the

border areas of the USSR. But they did not agree about what

should happen next. OKH argued that the main effort should

be made on the Moscow axis. Not only was the road and rail

net more extensive in that direction, but the Soviet

capital was a major industrial center and hub of

communications that the Red Army would no doubt be compelled to

defend, and whose loss might prove fatal to the Soviet

regime.

The Führer, however, had other

ideas: the capture of Leningrad and the seizure of Ukraine,

the USSR’s breadbasket and a major source of raw materials.

He argued that the loss of these territories would cripple

the Soviet war effort, and that their resources were

essential to sustain the German war effort. For the moment

this disagreement was papered over, Hitler telling

Brauchitsch and Halder that a final decision on future

operations would be made after the successful conclusion of

Barbarossa’s first phase.

German troops in Russia,

winter 1941-42 (Bundesarchiv)

But as things turned out,

the division of command responsibility and Hitler’s

non-decision on the second phase of Barbarossa stored up

trouble for the future. All might have been well if

the Russian campaign could have been finished off as planned

by the autumn of 1941. But for various reasons, prominent

among them the Germans’ underestimation of the USSR’s

military resources, this proved impossible. The last

lingering hopes for a quick victory dissipated with Hitler’s

decision to halt the drive on Moscow in July 1941 and divert

forces to the north and south, grasping for Leningrad and the

Ukraine. But the drive on Leningrad failed, leaving the city

besieged but still in Russian hands. And though a great victory was won at Kiev,

with some 600,000 troops of the Red Army killed, wounded or

made prisoner, strategically it led nowhere. Finally, when the

attack on Moscow was belatedly resumed in September it lacked sufficient

punch and stalled out with the onset of winter. Then came

the shock of the

first Soviet winter counteroffensive, which

for a time seemed to threaten the German Army with a defeat

of Napoleonic proportions. Though the immediate crisis was

mastered, it was clear to the generals and even to Hitler that Barbarossa had failed. The war in the east would go on—and

German’s prospects for winning it appeared increasingly

doubtful.

These alarming

developments had both short- and long-term consequences.

First, the Red Army’s 1941-42 counteroffensive provoked a

command shakeup on the German side, with many senior

officers dismissed. Once it became obvious that Moscow could

not be captured, the generals had advocated a general

withdrawal to a defensible winter line, but to this the Führer was adamantly opposed. He argued,

perhaps correctly,

that such a retreat would devolve into a rout, and demanded

instead

an all-out defense in place. Hitler got his way in this by

the simple expedient of dismissing von Brauchitsch and putting himself in direct command of

the Army. He thus united in his person the offices of head

of state, supreme commander of the armed forces as a whole,

and commander-in-chief of the Army. No longer could any

other individual or institution claim independent military

authority or responsibility. In effect, OKH was reduced to

the status of Hitler’s planning and operations staff for the

Eastern Front only. But even this relationship was

undermined by his distrust of the generals and the General

Staff as a whole—a distrust that developed into a mania as

the war went on and the tide turned against Germany.

The fragmentation of

military authority intensified the already bitter rivalry

between OKH and OKW, exemplified by endless wrangling over the

allocation of forces among the various fronts. One of the

key responsibilities of a military high command in wartime

is the management of reserves and military resources

generally. But by 1941 there existed in National Socialist

Germany no such responsible body. Only Hitler,

standing alone at the apex of a jury-rigged command

structure, could take fundamental decisions. And though on

more than a few occasions his judgment proved superior to

that of the

Generalität, the Führer

was unfitted by temperament or training for such a task: He had no

respect for institutions nor any understanding of corporate responsibility. Only

his will mattered—and the worse things went for

Germany, the more completely was the will of the Führer

substituted for rational calculation.

Department of History,

USMA West Point

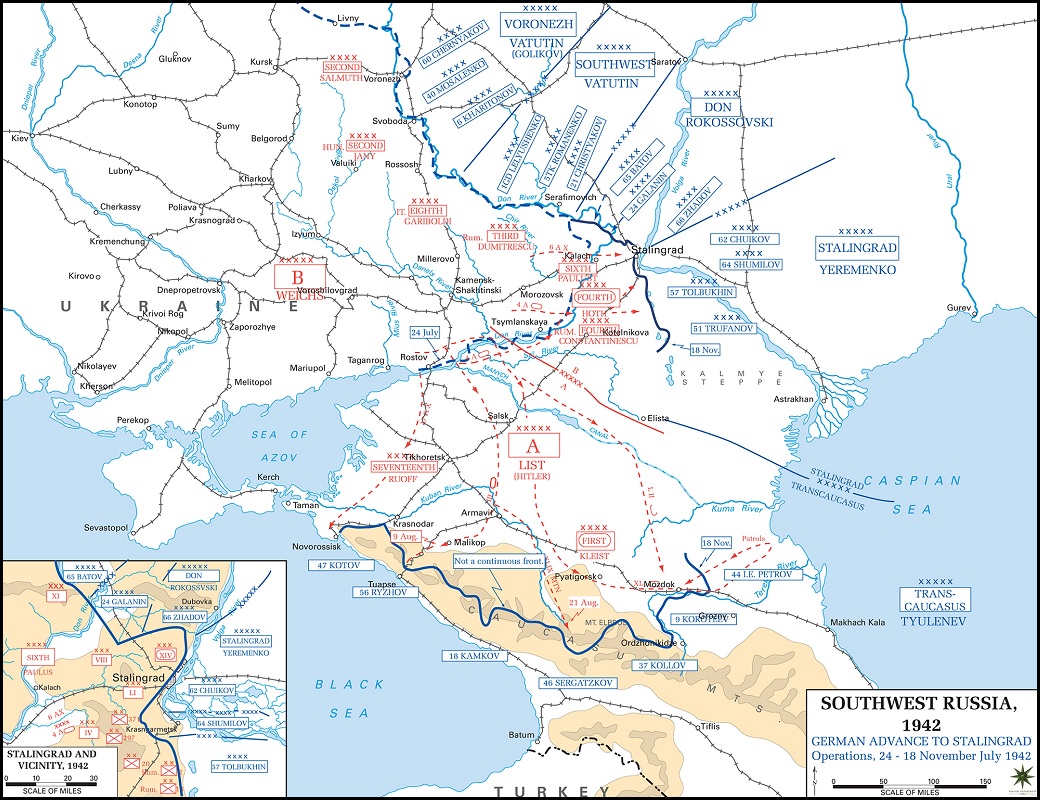

The disastrous results of

the 1942-43 campaign, beginning with the German summer

offense in the southern USSR and ending with the Stalingrad

debacle, laid bare both the impotence of OKH and the bankruptcy of German strategy.

Hitler’s decision to divide his forces in the southern USSR,

sending part toward Stalingrad on the Volga and part into

the Caucasus, was a grave strategic error, compounded by the Führer’s burgeoning obsession with the capture of the “city

of Stalin.” This set the stage for the second Soviet winter

counteroffensive, which trapped and destroyed Sixth Army at

Stalingrad. Coming as it did on top of defeat at El Alamein

in North Africa, Stalingrad clearly signaled the

psychological if not quite the military turning point of the

war.

In this way Stalingrad extinguished the last smoldering ashes of OKH's autonomy. From mid-1943 to the end

of the war, the High Command of the Army existed in name

only. Hitler had stripped it of all authority so that the

penultimate Chief of the OKH, Colonel-General Heinz Guderian,

appointed after the attempt on the Führer’s life (20 July

1944) spent much of his time in futile wrangling over petty

military details as Germany plunged inexorably into the

abyss of defeat. To that humiliating and dishonorable end

was the OKH brought by the devil’s bargain it had struck with Adolf Hitler and National Socialism.

● ● ●