|

● ● ●

NOTE ON

NOMENCLATURE

German

infantry divisions were called just that: Infanterie-Division.

Though all infantry regiments were retitled

as grenadier regiments (Grenadier-Regiment) in

1942, their parent divisions retained the Infanterie

designation. Mountain infantry divisions were called

Gebirgsjäger-Division

and the light infantry

divisions raised in 1941 were called

Jäger-Division.

(Jäger

is the traditional German term for light infantry.) The

divisions of the 32nd Wave, raised in 1944-45, were called

Volksgrenadier-Division. The second-line divisions

raised for occupation duties and coastal defense bore the

suffex (bo) for bodenständig

(static), indicating that they lacked sufficient transport

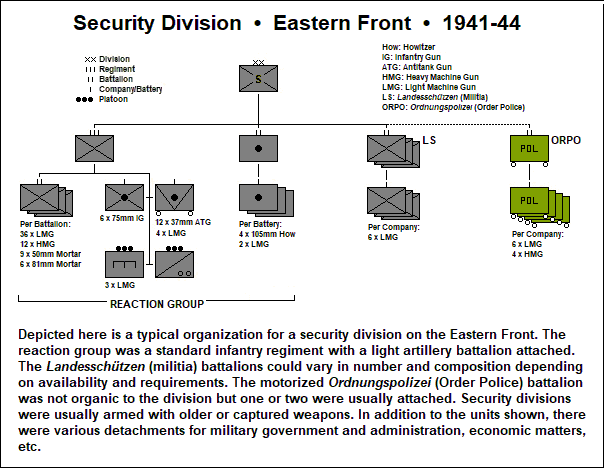

to move as a unit. The Sicherheits-Division

(security division) was configured for security and

anti-partisan operations in the rear areas of the armies,

especially in the USSR.

● ● ●

During World War Two

the German Army and the Waffen-SS (the military

branch of the SS) raised a total of 330 infantry divisions

. There were in

addition a number of Luftwaffe (Air Force) and Navy ground

combat divisions, formed from surplus personnel. If this

total seems impressive, it must be borne in mind that the

German divisions were very variable in quality. Nor did all

infantry divisions have an identical organization—this in

sharp contrast to the highly standardized British and

American infantry divisions.

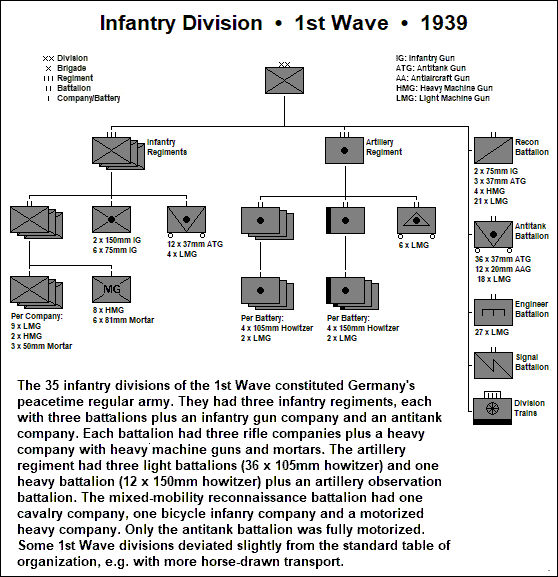

When the war began, the German Type

1939 Infantry Division was similar in structure to its

American and British counterparts, consisting of three

infantry regiments with three battalions each: the so-called

triangular organization. Additional infantry divisions were

mobilized in “deployment waves” (Aufstellungswellen), and

the divisions of each wave were structured according to the

tables of organization in force at the time of their

mobilization. The tables themselves were drawn up in accord with the

manpower and equipment available at the time, and in

addition there were several revisions to the standard

authorized organization that was, in theory though not in

practice, applicable to all divisions.

On 1 September 1939

the German Army had 85 infantry divisions available: those

of the 1st through the 4th Waves. The 1st Wave embodied the

35 active infantry divisions of the peacetime Army. Their

personnel consisted of 78% active soldiers, 12% Class I

reservists (12-24 months training), 6% Class II reservists

(2-3 months training) and 4% Landwehr (militia)

soldiers (mostly World War I veterans). The 2nd Wave

embodied the Army's sixteen first-line reserve divisions, manned in

peacetime by cadres and brought up to strength on

mobilization. Their personnel consisted of 6% active

soldiers, 83% Class I reservists, 8% Class II reservists and

3% Landwehr soldiers. The 3rd Wave embodied the

twenty Landwehr divisions,

which were maintained in peacetime at approximately 50%

strength and brought up to strength on mobilization. Their

personnel consisted of 1% active soldiers, 12% Class I

reservists, 46% Class II reservists and 42% Landwehr soldiers.

The 4th Wave embodied the first fourteen war mobilization

divisions (planned in 1938; mobilization ordered on 31 August 1939).

Almost half of their personnel were Class II reservists and

a quarter of the rest were in formed Landwehr units,

the precise breakdown being 8% active soldiers, 21% Class I

reservists, 47% Class II reservists and 24% Landwehr soldiers.

Command pennant

of the 86. Infanterie-Division. The

divisional insignia was also painted on vehicles.

In terms of training,

only the divisions of the 1st and 2nd Waves were considered

fully fit for active service. The divisions of the 3rd Wave

were considered to be ready for subsidiary missions only and those of

the 4th Wave were judged to require further training

before being committed to action. As for weapons, only the

divisions of the 1st Wave were fully equipped. The other

divisions lacked their authorized 150mm infantry guns, 20mm

antiaircraft guns and 50mm and 81mm mortars. Particularly

among the 4th Wave divisions, the weapons issued were

often older models such as the MG 08/15 light machine gun of

World War I vintage. Their field artillery battalions were

mostly equipped with unmodernized World War I-vintage guns

and howitzers, or with weapons taken over from the former Czech Army.

Though some of its elements, e.g.

the antitank (AT) battalion, were motorized, the infantry

division relied largely on horses to move guns and supplies.

The artillery was horse drawn; the division trains (supply

and transportation) had both motor vehicles and horses. The

infantry marched on foot. Trucks were in short

supply, a situation that got no better as the war

progressed. Even in 1939 many divisions could not be

provided with all the motor vehicles authorized by the

official tables of organization. Extensive use was made of

requisitioned civilian vehicles and captured enemy

vehicles, notwithstanding the serviceability and maintenance

problems this caused.

By May 1940 five more waves

embodying 41 infantry divisions had been mobilized, and

though they preserved the basic triangular configuration,

they were not organized identically. This was due mostly to the equipment shortages that plagued the

German Army throughout the war. The nine divisions of the

5th and 6th Waves received 81mm mortars but no 75mm or 150mm

infantry guns; their artillery consisted entirely of former

Czech Army howitzers and guns. Those of the 7th Wave had no

mortars or 150mm infantry guns and only 24 x 105mm howitzers

in their artillery regiments. In the 7th, 8th and 9th Waves, the

separate AT and

reconnaissance battalions were

replaced by a composite battalion with one AT company and

one bicycle infantry company. The 9th Wave divisions were

mobilized initially with an artillery component consisting

of a single battery: 6 x 75mm field guns captured from the

Polish Army.

Some waves produced

divisions for special purposes. Those of the 15th Wave, for

example, were the first of the so-called static (bodenständig)

infantry divisions. As the designation implies, these

divisions were configured for occupation duties and static

defense. As raised they had two regiments, each with three

battalions, plus a single artillery battalion. Generally the

static divisions received lower-quality manpower, were armed

with older or captured weapons and lacked sufficient transport to

move as a unit. The 16th Wave consisted of four security (Sicherungs)

brigades, soon merged into two security divisions.

Seven more such divisions were raised outside the wave

system, mostly by converting existing

infantry divisions. The security divisions embodied

a “reaction group”—essentially an infantry regiment with an

attached light artillery battalion—and a

variable number of second-line militia (Landesschützen)

battalions and military government units. Usually they also

had an attached motorized battalion of the

Order Police.

Troops of a security division in

Russia, 1942 (Photo: World War Photos)

A serious

problem for the German Army—increasingly so as the war

dragged on—was the shortage of manpower. Thanks to this, the

size of the standard infantry division had progressively to

be reduced. Incremental cuts were made between 1941 and

1943, lowering the infantry division's authorized strength

from around 17,500 to 15,000, but by late 1943 it was clear

that much more drastic reductions were

necessary. The result

was the Type 1944 Infantry Division

(Infanterie-Division Kriegestat

44).

One battalion was

removed from each infantry regiment, leaving the division

with a total of six, and the platoons of the rifle companies were reduced

from four squads to three. The reconnaissance battalion

was eliminated, being replaced by a so-called fusilier

battalion with heavy weapons. One infantry company of this battalion,

mounted on bicycles, was the division's reconnaissance unit.

The Type 1944 division's authorized strength was

12,772, representing an overall manpower cut of 27% and a

31% cut in infantry strength. The loss of manpower was

partially offset by increasing the division’s firepower with

more machine guns, heavy mortars and infantry antitank

weapons.

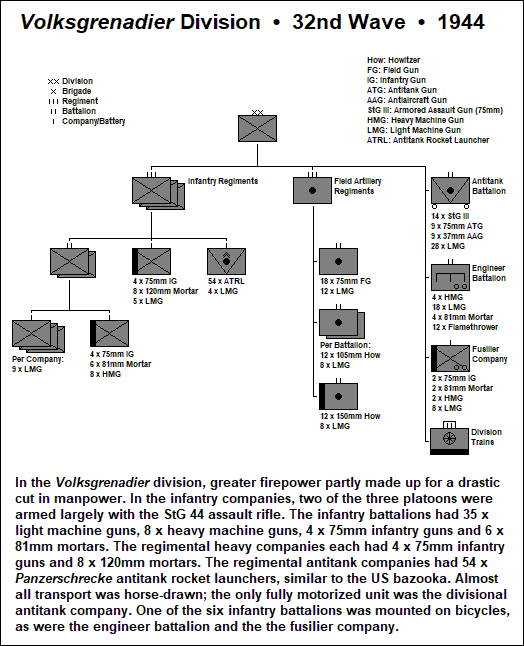

In mid-1944, twin

catastrophic defeats in Normandy and Byelorussia effectively

destroyed over 60 divisions. To replace them some 50 new

infantry divisions were raised: the so-called People's

Grenadier Divisions (Volksgrenadier-Division).

Twenty-six VG divisions were new units of the 32nd Wave;

the rest were rebuilt divisions that had been shattered in

combat. Manpower was again cut, this time to 10,072, and though automatic

weapons were issued on a big scale, the VG division's

firepower was lower than that of the Type 1944 division. The

quality of these hastily raised divisions was variable, the

conscripts who filled out their ranks having received

minimal training. VG divisions formed around a core of

veterans tended to perform well; others were little better

than armed mobs. the Type 1945 Infantry Division (Infanterie-Division

Kriegestat 45)

was similar to the VG division, albeit with a lesser

allotment of automatic weapons; few if any were raised in

time to see combat before the war ended.

Sketch diagram, probably made by a

staff officer, depicting the organization of the 361. Volksgrenadier-Division.

(Bundesarchiv)

In all there were 38

waves of infantry divisions raised during the war—the last

of them as late as April 1945. Additionally there were

numerous infantry divisions and brigades raised outside the

wave system on an emergency basis, usually by rebuilding

divisions that had been destroyed in combat, filling them up

with conscripts or drafting in personnel from other units,

or by upgrading regiments and brigades. An example of the

latter was the 1. Skijäger-Division,

formed on the Eastern Front in 1944 by expanding the 1. Skijäger-Brigade to division strength. The infantry

divisions of the Waffen-SS and the Luftwaffe were also

raised outside the wave system, and usually their

organization differed from that used by the Army at the

time.

After a few weeks—sometimes just a

few days—of service at the front, divisions were well below

their authorized strength. Personnel killed, wounded or

evacuated sick could seldom be replaced on a one-for-one

basis and even when that was possible, divisions received

sketchily trained conscripts in exchange for experienced

veterans. When a division was "burned out," the usual

practice was to withdraw it to some quiet area for

rebuilding. Many exhausted divisions from the Eastern Front

were sent to France for this purpose—before D-Day turned

that country into an active theater of operations.

Toward the end of

the war, with the enemy at the gates of the Reich, the

Army's

replacement, training and mobilization system broke down

completely. Men were snatched from here, there and

everywhere to bolster the ranks of skeleton divisions: from

the Luftwaffe, the Navy, the Labor Service, the Hitler

Youth. New divisions with sonorous titles like Scharnhorst and Ferdinand

von Schill were thrown together and expended in a

frantic, futile attempt to stem the tide. It was the

culmination of a long process of decline, the last gasp of

an army driven to the limit of its endurance.

● ● ●

|