|

● ● ●

The history of the

modern US Army infantry division begins with the National Defense

Act of 1916, which provided for an increase in the size of the

Regular Army and the establishment of a permanent divisional

organization. Up to then the largest permanent organization had been

the regiment, and the last time that divisions had existed in large

numbers was during the Civil War.

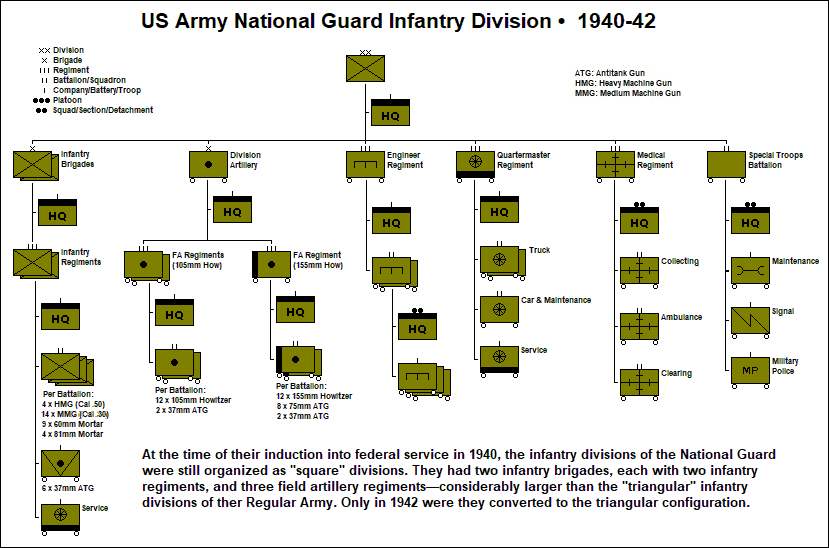

The organization

adopted for the Army division in 1916, which would also apply to the

National Guard, was “triangular”: three infantry brigades, each with

three infantry regiments, plus artillery and other support units.

(At that time an infantry regiment had the actual strength of a

battalion.) But not much was done to implement this scheme and by

the time that the United States entered World War I in the spring of

1917 it was considered obsolete. Instead, the Army adopted a much

larger “square” organizational template: two infantry brigades, each

with two infantry regiments, each regiment with three battalions.

The square division also had a field artillery brigade with three

regiments (six battalions), an engineer regiment, and a machine gun

battalion. With various modifications, this square configuration

remained standard for the Army’s infantry divisions up to 1939.

In combat the square

division had demonstrated considerable staying power—due to its

size—but it lacked mobility and proved difficult to support. After

the war considerable thought was given to the development of a new,

smaller, more mobile infantry division, with motor vehicles

replacing horses. The ultimate result was a new triangular

organization. The infantry brigades and one of the infantry

regiments were eliminated, the division artillery was reduced to

four battalions, and support units were reduced in proportion. The

overall reduction in manpower was from 22,000 to about 12,500.

The new organization

was approved in 1939 and by late 1941 all infantry divisions of the

Regular Army were triangular. The divisions of the National Guard,

however, retained their square configuration. The reason for this

was partly political. Converting the NG divisions from square to

triangular would deprive many officers of their commands—a prospect

most unwelcome in both the states and the National Guard Bureau.

Only a year to eighteen months after their induction into federal

service (1940-41) were they finally converted.

The officer most

influential in the design of the wartime triangular infantry

division was Lieutenant General Leslie J. McNair, who was Chief of Staff,

General Headquarters (GHQ) US Army from 1940 to 1942 and then

Commanding General, Army Ground Forces (AGF) when that organization

replaced GHQ. He served in the latter capacity until he was killed

in France on 25 July 1944. McNair had been involved in issues of

Army reorganization since the mid-1930s, when he championed the

concept of a lighter, more nimble infantry division. As commander of

AGF, he held primary responsibility for the organization,

mobilization and training of all Army ground combat forces: an

undertaking of vast complexity, embracing a myriad of factors.

Lieutenant General Leslie J. McNair

as Commander, Army Ground Forces in 1942. (US Army Signal Corps)

One great challenge

that McNair faced was the integration of new weapons into the

infantry division. This affected the organization of the infantry at

every level, from the rifle squad to the regiment. In 1935 the

primary infantry weapons were the bolt-action Springfield rifle; the

Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR); the tripod-mounted, water-cooled

30-caliber Browning machine gun; and the 81mm Stokes mortar of World

War I vintage. In 1938-40, however, new weapons began to be

introduced: the M1 self-loading rifle, a greatly improved BAR, the

Thompson submachine gun, a lighter air-cooled version of the

Browning machine gun, the .50-caliber heavy machine gun, the light

60mm mortar, the 37mm antitank gun. All these new weapons greatly

increased the infantry division’s firepower, despite the reduction

in manpower.

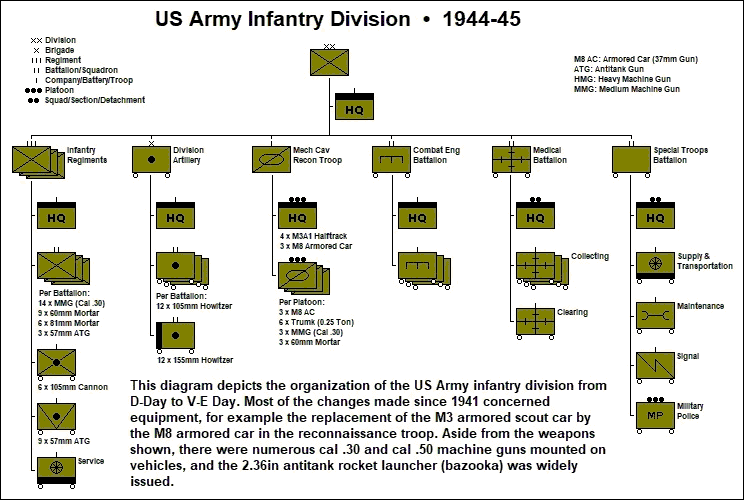

The triangular

infantry division underwent various alterations between 1941 and

1944, but none of these changes affected its basic organization. The

divisional antitank battalions that existed in two or three

divisions in 1941 were removed and allocated to the new Tank

Destroyer Force when it was established late in that year. In

mid-1942 the quartermaster battalion (supply, transport and

maintenance) was dissolved and replaced by separate quartermaster

and maintenance companies. The infantry regiments acquired a cannon

company with six light 105mm howitzers. New and improved weapons

were introduced, such as the M8 armored car (37mm gun) in place of

the machine gun-armed M3 armored scout car, and the 2.36-inch

antitank rocket launcher (bazooka). The ultimate configuration of

the triangular infantry division (1944-45) is shown in the

accompanying diagram.

Distinguishing Flag of the 1st Infantry Division:

"The Big Red One"

Though many of its

sub-units such as the division artillery and the

cavalry

reconnaissance troop were fully motorized, the infantry division as

a whole was not. Though American industry was more than capable of

providing the necessary motor vehicles, Army planners judged that

full motorization of infantry divisions would place excessive demand

on the shipping needed to deploy them to Europe and the Pacific.

(The same considerations led to a reduction in planned armored

divisions from the fifty or sixty envisioned in 1941-42 to the

sixteen ultimately activated.) Instead, quartermaster truck

companies would be attached to infantry divisions as necessary. One

such company, with its 48 x 2.5-ton trucks and 1-ton trailers, was

capable of fully motorizing an infantry regiment.

Nor did the infantry

division include anything in the way of armored fire support

vehicles. In the 1920s the Army distinguished between infantry tanks

(providing such support) and “combat cars” (light tanks in the

cavalry branch) but the evolution of mobile/mechanized combined arms

doctrine did away with this distinction. In 1940 the Infantry branch

lost all control over tank development. While it was recognized that

tank support was vital to the infantry, this would be provided by

independent tank (later armored) groups of two or three tank

battalions. Such groups proved excessively large, however, and

during World War II it became common practice, particularly in the

European theater, to attach a separate medium tank battalion to each

infantry division on a more or less permanent basis. Typically, the

battalion’s three medium tank companies were parceled out to the

division’s infantry regiments. The light tank company could be

attached to the division’s mechanized reconnaissance troop or, with

other battalion elements, held under control of the division HQ as a

mobile reserve.

Infantry rifle squad and M4 Sherman

medium tank. (US Army Center of Military History)

The attached tank

battalion was sometimes augmented or replaced by a self-propelled

(SP)

tank destroyer battalion. The SP tank destroyer resembled a medium

tank but it was faster, had lighter armor and an open-topped turret,

and mounted a more powerful main gun. Prewar doctrine had envisioned

TD battalions operating in groups of three or four against enemy

armored forces. But large-scale armored clashes on the Russian Front

model were rare in the European and Pacific theaters and the TD

battalions were mostly attached to armored and infantry divisions.

In the infantry

division both tanks and SP tank destroyers were employed as assault

guns. Individual tanks operating with infantry platoons proved

extremely useful in the 1944-45 Siegfried Line battles, knocking out

enemy bunkers and providing direct fire support for advancing

infantry. The more lightly armored tank destroyers were not quite so

successful in this role, though their high-velocity main guns were

highly effective bunker busters.

No doubt the most

prominent strong point of the triangular infantry division was the

division artillery. This consisted of four battalions: three with a

total of 36 x 105mm howitzers and one with 12 x 155mm howitzers. Not

only were the weapons themselves of excellent design and

performance, but their tactical employment was devastating

effective. Advanced communications and fire direction techniques

made it possible to engage targets rapidly and to mass the fires of

the entire division artillery on a single target. (The organization

and employment of US Army field artillery in World War II will be

covered more fully in a forthcoming article.)

But there were

challenges as well. The most pressing, which became acute in the

European theater during 1944-45, was a shortage of infantry

replacements. In early December 1944, for example, Patton’s Third

Army was 11,000 infantrymen short: roughly the rifle strength of two

infantry divisions. There were two reasons for this: combat

casualties in the infantry and the difficulty of replacing them.

Once a division

entered combat, the main burden of the fight inevitably fell on the

infantry and after a few weeks it was common for a rifle platoon or

company to have suffered nearly 100% casualties—meaning that almost

all of its original personnel had been killed, wounded, evacuated

sick or reported missing. Particularly serious was the loss of

trained small-unit leaders—junior officers and NCOs. These losses,

bad enough in themselves, proved especially hard to replace.

Competing demands for manpower, among the armed forces and among the

branches of the Army itself, meant that there were never quite

enough men allotted to the infantry. And late in the war, the

manpower that was allotted of indifferent quality: 18-year-olds with

less than six months’ training, older classes of draftees, often

with poor educational qualifications. Thus infantry battalions found

themselves manning the line with critical gaps in their ranks, and

little time to absorb the often sketchily trained replacements that

they received.

The Army had been

grappling with this manpower problem since 1942; it was a major

factor in General Marshall’s 90-division gamble. In late 1944,

emergency measures were adopted. Many antiaircraft artillery units,

surplus to requirements after the effective demise of the Luftwaffe,

were disbanded and their personnel distributed as infantry

replacements. Rear-echelon units were similarly assessed and either

disbanded or reduced in strength. But these measure, while helpful,

could not solve the manpower problem, which was by then systemic.

Fortunately, however, Germany was by then on the brink of defeat,

with many of its own divisions reduced to pitiful remnants.

Immediately after

the termination of hostilities in Europe, the General Board,

European Theater of Operations, United States Army, was set up to

conduct a wide-ranging review of the organization, equipment, and

tactical employment of the infantry division in light of combat

experience. The Board's general conclusion was that the wartime

triangular infantry division's major subordinate elements were

insufficient to carry out independent combat operations.

Particularly remarked upon was the lack of an organically assigned

tank battalion. Other recommendations included the addition of an

antiaircraft artillery battalion, a strengthening of the division

artillery, the expansion of the mechanized cavalry reconnaissance

troop into a full squadron, and the augmentation of the division's

service and support elements. In the postwar period most of these

proposals were adopted, though the basic triangular configuration of

the infantry division was retained until it was replaced by the

Pantomic organizational scheme in the late 1950s.

● ● ●

|