Note: At

the beginning of World War II the artillery of the US Army

was divided into two branches: Field Artillery (FA),

nicknamed the Redlegs, and the Coast Artillery Corps (CA),

nicknamed the Cosmoliners. This article covers the FA only.

World War II FA

weapons were of two types: guns and howitzers. The former

were long-range, flat-trajectory weapons; the latter were

medium- to long-range weapons capable of high-trajectory

fire.

● ● ●

When it

was all over, General George S. Patton said, “I do not have

to tell you who won the war. You know. The artillery did.”

There

was some hyperbole in this, but Patton had a point.

Without doubt, the FA was the most impressive branch of the

wartime US Army’s combat arms. Its weapons and equipment

were of the highest quality; its technical and tactical

competence was second to none. The Army had closely studied the lessons of

the Great War, particularly as related to the role of

artillery. When the time came to prepare for a new war, the

organization of the FA was carried out systematically; that

is, instead of thinking in terms of guns, men and units, the

Army created an integrated artillery system.

But without guns there is no

artillery. In the Great War, the FA had been largely reliant

on British and French equipment, especially the M1897 75mm

field gun, the M1917 155mm gun and the M1917 155mm howitzer,

all of French origin. These weapons soldiered on in the

postwar army and saw service in the early days of World War

II, but by then a new range of weapons had been designed to

replace them. The artillery of the infantry division came to

be based on two models: the M2 105mm light field howitzer

and the M1 155mm medium field howitzer. Both were excellent

weapons, destined to serve for many years. Modernized

versions of both still equipped National Guard artillery

units as late as the 1980s.

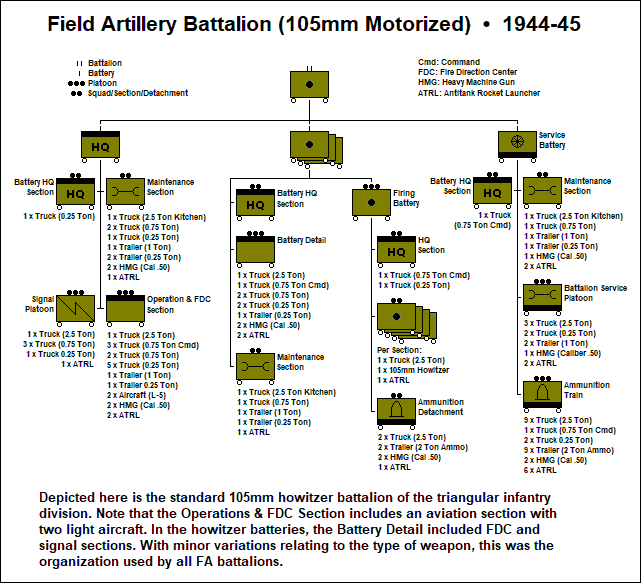

By 1941

these weapons were well integrated into the Army’s combat

divisions. In 1940-41 the

infantry divisions of the Regular

Army had been reorganized from the World War I-era square

configuration (two infantry brigades, each with two

regiments) to a triangular configuration (three infantry

regiments, each with three battalions). The triangular

division’s artillery component consisted of four separate

FA battalions, three with 12 x 105mm howitzers each, and one

with 12 x 155mm howitzers. There was no regimental

headquarters and the four battalions were controlled by the

Division Artillery (DIVARTY), essentially a brigade-echelon

tactical headquarters. (The infantry divisions of the

National Guard remained in the square configuration until

they were inducted into federal service in 1940-41, at which

time they became triangular.)

In 1941,

armored divisions were organized under what later was termed

the heavy configuration. Their artillery component consisted

of seven batteries, each with 4 x 105mm howitzers, halftrack

towed. Four were under a regimental headquarters in the

division’s armored brigade; the other three were in a separate

battalion. There

was no DIVARTY HQ. In 1942, divisional artillery was

reorganized into three battalions, each with 18 x self-propelled (SP)

105mm howitzers, the regimental HQ was eliminated, and a DIVARTY HQ was provided. When most

armored divisions were reorganized under the 1943 light

configuration, their artillery component remained the same:

three Armored FA Battalions, as by then they were

designated.

The

DIVARTY of airborne divisions had three battalions, each

with 12 x M1 75mm pack howitzers: one designated Parachute FA

Battalion, the other two designated Glider FA Battalion. in

1943-44 a fourth Glider FA Battalion equipped with the M3

105mm light howitzer was attached to some airborne

divisions, and by early 1945 this battalion was present in

all airborne divisions. The two

cavalry divisions in existence in 1941 had three FA

battalions: two with 12 x 75mm howitzers, horse drawn, and

one with 12 x 105mm howitzers, motor towed. Neither division,

however, saw action as horse cavalry during the war.

Distinguishing Flag, 333rd

Field Artillery Group (Colored)

The Army's nondivisional artillery consisted mostly of howitzers and

guns with a caliber of 4.5in (115mm) or greater, though

there were some 105mm towed and SP howitzer battalions. Such

units were intended to serve as corps and field army assets,

and at the beginning of the war they were organized as

regiments and brigades. In late 1942, however, the Army

decided to abolish the regimental structure in all branches

but infantry, replacing it with a flexible group

organization. Nondivisional FA regiments were reorganized as

follows (using the 333rd FA Regiment as an example). The

regimental headquarters became Headquarters and Headquarters

Battery (HHB) 333rd FA Group, the 1st Battalion became the

333rd FA Battalion, and the 2nd Battalion became the 969th

FA Battalion. All three were then separate, self-contained units, though

usually the battalions were attached back to the group. An

FA group could control up to four battalions, as did the

333rd FA Group by D-Day. Most FA brigades were inactivated,

though some, already overseas, remained in being.

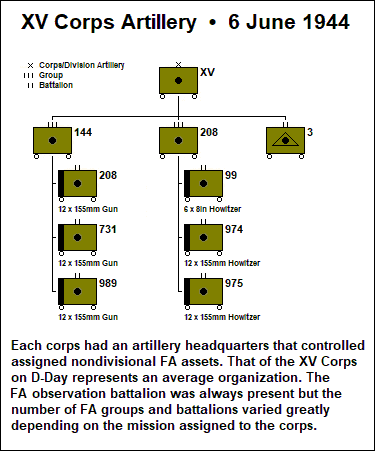

Nondivisional FA battalions were equipped with the following

weapons: M7 105mm (SP), M1 155mm, M1 8in and M1 240mm

howitzers; M1 4.5in, M1 and M40 (SP) 155mm and M1 8in guns.

The 4.5in and 155mm battalions had twelve guns or howitzers;

the 8in and 240mm battalions had six. A typical allotment of

nondivisional artillery to a corps or field army was VIII

Corps Artillery on 6 June 1944: two FA groups controlling

six FA battalions (155mm and 8in howitzers; 155mm guns) plus

an FA observation battalion (see below).

Unlike

the artillery of the German Army, which remained partly

reliant on horses for mobility, the US Army’s FA battalions

were completely motorized or mechanized. The Armored FA

Battalion’s M7 SP 105mm howitzer (based on a modified M3 or

M4 tank chassis) greatly enhanced the weapon’s mobility and

provided its crew with a measure of armor protection. The

infantry division’s 105mm howitzers were towed by the

ubiquitous 2.5-ton cargo truck; heavier guns by various

models of tractor. A towed 105mm howitzer battery in an

infantry division had 7 x 2.5-ton trucks, 5 x 0.75-ton trucks

(known as the weapons carrier) and 3 x 0.25-ton trucks (the

famous Jeep). There were also five trailers of various cargo

capacities.

The FA system referred to above

integrated the core tasks relating to artillery:

observation, target acquisition, communications and fire

direction. It was this system that made the US Army artillery

so effective in action.

Observation was just that: observing and correcting the fall

of shot to adjust fire onto the target. This was the job of

the FA forward observer (FO) teams. These teams were

attached to infantry and armor units, and linked by radio to

the fire direction center (FDC) of their parent FA

battalion. Their presence on the front line enabled targets

of opportunity to be quickly identified and accurately

engaged: the FA direct support mission.

A 105mm howitzer battery

with an aerial observer aircraft overhead (US Army Center of

Military History)

It was

found, however, that insufficient FO teams could be provided

to guarantee timely artillery support for dispersed infantry and armor units

in action. This gap was filled by air observation. In the

infantry and armor DIVARTY, the headquarters and each FA

battalion had an air observation section with two light

liaison aircraft for a total of ten in the infantry

division or eight in the armored division. The aircraft was

either the L-4 Grasshopper, a militarized variant of the

popular Piper J-3 Cub, or the Stinson L-5 Sentinel, purpose

built for the military. Though the Air Corps provided ground

crews and technical support, the air observation sections

were part of the FA, the pilots and observers being FA

officers. The ability to spot targets and call for fire from

the air greatly enhanced the FA’s flexibility.

Despite

its designation, the Field Artillery Observation Battalion

was primarily concerned with target acquisition on behalf of

nondivisional corps artillery. These battalions were

organized with a headquarters battery and two observation

batteries, each of which had a sound ranging platoon and a

flash ranging platoon. The battalion’s missions were

location of hostile artillery, registration and adjustment

of artillery fire, coordination of survey, artillery

calibration, and providing the meteorological message to

supported units.

Secure, rapid communication was

facilitated by the signal units attached at each echelon of

command, providing FA units with their own radio and

telephone nets. The FM radio had been adopted before the war

and it proved very satisfactory in service. DIVARTY

and FA group headquarters maintained a command net linking

to their subordinate battalions, and battalion headquarters

did likewise, linking to their subordinate batteries. Thus

calls for fire from observers and fire orders from higher

headquarters could quickly be passed along the chain of

command.

FA fire

direction had two facets: tactical and technical. Tactical

fire direction was basically the coordination of FA fires

with the division’s tactical planning: identification and

prioritization of targets, preparation of fire plans,

standardization of fire commands, employment of smoke, integration of other assets into fire

planning (e,g. corps artillery battalions, infantry regiment

cannon companies, 4.2in mortar units) and other matters.

Generally this was done in the operations section of the

DIVARTY HQ, though some tasks could devolve on the battalion

fire direction centers (FDC). Since all echelons of command were

linked in a divisional FA radio net, FA fires could be

divided or massed as required. The most fearsome massing of

fires was the time-on-target (TOT) mission, by which the

fires of multiple FA batteries or battalions were timed to strike a

target simultaneously—with devastating effect.

Field training exercise

for a Battery FDC section (National World War II Museum)

Technical fire direction—the actual computation of firing

data for howitzers and guns—was done at the battalion and

firing battery levels. The technical fire direction process

converted range and direction to the target from each

battery position into elevation, deflection and fuse

settings, with such variables as propellant temperature,

meteorological conditions and differences in altitude

between the guns and the target incorporated into the

solution. Standardized procedures enabled this task to be

completed rapidly by well-trained FDC personnel.

Nondivisional FA battalions were

similarly controlled by the corps artillery and FA group HQs

to which there were assigned.

Immediately after the termination

of hostilities in Europe, the General Board, European

Theater of Operations, United States Army, was set up to

conduct a wide-ranging review of the organization,

equipment, and tactical employment of the infantry division

in light of combat experience. The Board's conclusion was

that the wartime triangular infantry division's major

subordinate elements were insufficient to execute

independent combat missions. Its recommendation on the

division artillery was that although its basic structure was

valid, it should be strengthened. This was done by

increasing the firing batteries from four to six howitzers,

for a division total of 54 x 105mm howitzers and 18 x 155mm

howitzers.

Postwar analysis disclosed that in

Tunisia, Sicily, Italy and northwest Europe, some 85-90% of

total casualties inflicted by US forces on the German enemy

were due to artillery fire. Numerous German soldiers, from

enlisted men to senior officers, testified that the FA was

the most feared and respected branch of the US Army. In

World War II, the Redlegs well earned their title: “King of

Battle.”