The World War II US Army was

unusual in establishing a separate branch embodying antitank

units and personnel. The startling success of the German

Army’s Panzerwaffe in Poland and France focused the

Army leadership’s attention on the importance of antitank

defense. To the new triangular

infantry division, therefore,

an infantry antitank (AT) battalion was added. Additionally,

the division’s three infantry regiments each received a

separate AT company, for a divisional total of 72 x 37mm

antitank guns (ATG). The guns and personnel were drawn from

the Field Artillery branch, which thereby lost control of

antitank gunnery. But as things turned out only two

divisions actually received this battalion, for as they were

being set up the Army’s thinking on AT defense continued to

evolve.

Lieutenant General Leslie McNair,

the Chief of Staff, General Headquarters (GHQ), US Army,

believed that it was wasteful for tanks to oppose tanks on

defense when a much cheaper ATG could do the job. But even

so it seemed obvious that a unit with more firepower and

mobility than the infantry AT battalion would be required.

Thus was born the concept of the tank destroyer (TD)

battalion: a self-contained nondivisional antitank unit

capable of conducting a mobile defense against attacking

enemy armor.

On 27 November 1941 the War

Department ordered the activation of 53 TD battalions under

the direct control of GHQ. The two existing infantry AT

battalions were transferred from their parent divisions and

reorganized accordingly. Also ordered was the

establishment of a Tank Destroyer Tactical and Firing Center

at Fort Meade, Maryland. The Center was made responsible for

TD doctrine, equipment and training. Soon thereafter the

Tank Destroyer Force (TDF) became a separate Army branch.

Distinguishing Flag, 1st

Tank Destroyer Group

Two fundamental questions

confronted the new TDF: How were TD battalions to be

organized and equipped, and how were they to be employed?

The first question was quickly resolved thanks to the

existence of the 93rd AT Battalion, an experimental

nondivisional unit that had successfully participated in the

1941 Carolina maneuvers, a major field training exercise.

Renumbered from 93rd to 893rd, it became the prototype TD

battalion. Initially there were three authorized

organizations, one towed (T) and two self-propelled (SP):

the light TD battalion (T), the light TD battalion (SP) and

the heavy TD battalion (SP). The light battalions had 36 x

37mm ATG, either towed by 0.25-ton trucks (the ubiquitous

Jeep) or mounted on a 0.75-ton truck (M6 TD). It being

recognized that the 37mm ATG was verging on obsolescence,

these battalion types were considered interim organizations.

The desired unit was the heavy TD

battalion (SP), whose primary equipment was the M3 halftrack

mounting an M1917 75mm gun. The M1917 was the American

version of the famous “French 75” of World War One vintage,

which had proved effective in the AT role against German

armor in 1940. The M3 was an interim design, eventually to

be replaced by the fully tracked tank destroyer already in

development, but it saw combat in the Philippines, North

Africa and Sicily, and was also employed by the Marine Corps

in the Pacific.

The heavy TD battalion embodied a

battalion headquarters company, a reconnaissance company and

three TD companies, each with three platoons. Two of the

platoons had 4 x M3 TD each and one had 4 x M6 TD. The

platoons also had an SP antiaircraft section with 2 x

caliber .50 antiaircraft machine guns (AAMG). The M6 platoon

was earmarked for upgrade to heavier equipment when it

became available. The headquarters company consisted of a

command section plus signal, transportation, maintenance and

supply platoons. The reconnaissance company had three scout

platoons and a pioneer (engineer) platoon. The first SP TD

battalions to see action in North Africa were organized in

this manner.

The M3

Tank Destroyer (75mm gun) saw action with

the US Army in the Philippines, North Africa

and Sicily (1941-43), and with the US Marine

Corps in the Pacific (1943-45).

(US Army Center

of Military History)

Though the Army envisioned an

ultimate force in excess of 200 TD battalions, only 106 were

actually activated during the war and for various

reasons—industrial priorities, shipping space—not all of

them could be SP units. So a heavy TD battalion (T),

organized similarly to the SP battalion but with the guns

towed by halftracks, was also specified. The AT gun was the

3in M5, which combined the barrel of the 3in antiaircraft

gun (AAG), already in service, with the suitably modified

breech, recoil mechanism and carriage of the 105mm M2

howitzer. For both

battalion types, overall manpower was cut from 900 to about

650 by eliminating the AAMG sections and streamlining the

headquarters company.

Development of a fully tracked tank destroyer to replace the

M3 had begun in 1940. Various designs were evaluated and

rejected before the T35E1 model was approved for production

as the M10 in June 1942. This tank destroyer was based on

the chassis of the M4A2 medium tank, with an open-topped

turret mounting the 3in M7 ATG—a modified M5—and a caliber

.50 heavy machine gun (HMG). Though bearing a superficial

resemblance to a tank, the M10 had much thinner armor and

was expected to rely for protection on speed and agility.

The M10 was destined to be the Army’s most numerous tank

destroyer of the war, with around 6,500 manufactured. Late

in the war it was supplemented by the M18 (76mm gun) and the

M36 (90mm gun).

The M10 Tank

Destroyer (3in gun) was based on the chassis of

the M4A2 medium tank. Though it superficially

resembled that tank, the M10 had thinner armor,

higher speed and a more powerful main gun than

the M4A2. (Tank Encyclopedia)

Doctrine governing the employment

of tank destroyer forces was based on theoretical

conceptions of armored warfare, studies of the 1939-41

campaigns in Europe, and experience acquired in the Army’s

own field exercises. These led to the conclusion that a

static antitank defense would be inadequate in the face of

tanks attacking en mass.

What was required was

active defense in depth. This could of course be provided by

one’s own tanks, but then they would be unavailable for

offensive action. Instead, mobile tank destroyer forces

would do the job, deploying rapidly to contain any enemy

armored breakthrough by occupying key terrain behind the

front line, launching counterattacks and aggressively

opposing the enemy’s advance.

Such

tactics required a higher headquarters to coordinate the actions of the TD battalions: the tank destroyer

group, a brigade-level echelon capable of controlling up to

four TD battalions. The TD group was purely a tactical

headquarters, with no responsibility for logistical support

of its subordinate battalions. This group organization,

which was later extended to all Army branches except the

Infantry, was intended to provide the flexibility necessary

to carry out the TD mission.

The Tank Destroyer Force had its baptism of fire in North

Africa—with mixed results. The problem was not due primarily

to poor leadership and training—though instances of such

deficiencies were noted—but to faulty doctrine. The concept

of aggressive defense in depth proved problematical in

opposition to the German Army’s tactics, which were based on

the combined-arms Kampfgruppe

(battle group). Rather than charging forward en

masse, the panzers

operated in close cooperation with infantry and artillery,

always covered by a screen of mobile antitank guns. Thus the

US tank destroyers, with their thin armor, were severely

disadvantaged. In only one instance were they able to fight

as they had trained. The 601st TD Battalion, an SP unit

equipped with the M3 and reinforced by a company of the

899th TD Battalion with M10s, turned back an attack by some

fifty tanks of the 10th Panzer Division at El Guettar

(Tunisia). Employing fire and movement, the US tank

destroyers accounted for some thirty panzers but the price

was high: 20 of 28 M3s plus seven M10s were knocked out.

An M5 antitank

gun being prepared for action. The weapon itself

was effective, but towed guns proved vulnerable

due to their relatively low mobility compared

with self-propelled tank destroyers.

(US Army Center

of Military History)

More

typically, the tank destroyers operated in close support of

the infantry, usually being allotted by companies and

platoons to infantry battalions and companies. Perforce,

they developed methods of cover, concealment and combat that

prewar doctrine had never anticipated. Instead of operating

independently, tank destroyers reinforced the infantry’s

antitank defenses. Instead of fighting on the move, they

were sited in carefully chosen, well-camouflaged firing

positions. In this role they proved useful but such

attachments caused considerable logistical and command

problems, such that senior commanders’ dissatisfaction with

the whole tank destroyer concept grew steadily as the

Tunisian campaign wore on. And in fact, there would never be

an opportunity for the tank destroyers to operate in their

originally conceived role. The large-scale armored clashes

of the early years of the war and on the Eastern Front were

not repeated in Sicily, Italy or Northwest Europe, where the

Germans fought largely on the defensive. Thus by 1944 tank

destroyer battalions found themselves attached more or less

permanently to infantry and armored divisions. In most cases

they remained administratively subordinate to their TD group

HQ, but these no longer exercised tactical control. TD group

HQs deemed surplus to requirements were either dissolved or

used to form a third, reserve combat command HQ for armored

divisions (CCR).

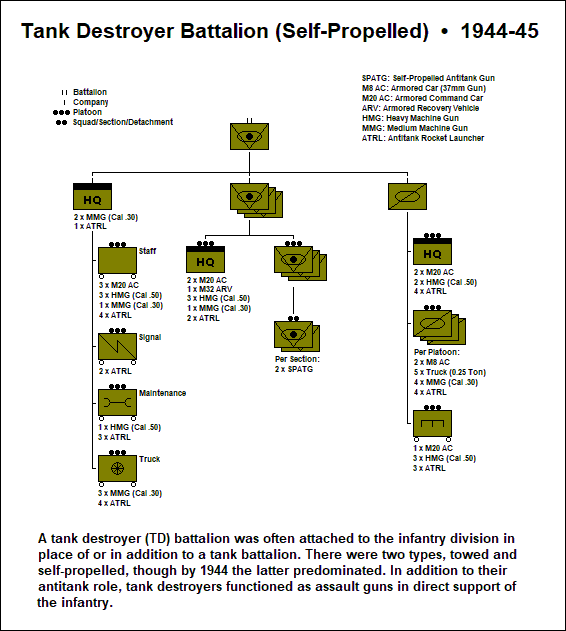

Fortunately, as the Tunisian campaign had shown there were

other viable missions for the tank destroyers. The US infantry

division’s organic antitank assets were minimal: 21 x 57mm ATG, three in the divisional headquarters company and

eighteen in the regimental AT companies. The attachment of a

TD battalion was, therefore, a welcome reinforcement. SP

tank destroyers also served as assault guns in close support

of the infantry. With their high-velocity main armament they

were effective bunker busters, though their thin armor and

open-topped turrets made

them more vulnerable than tanks. They were also employed as

regular artillery firing high-explosive ammunition, the

necessary techniques having been developed during the

Tunisian campaign.

Shoulder Sleeve Insignia

of the Tank Destroyer Force 1941-46. (US Army Institute of

Heraldry)

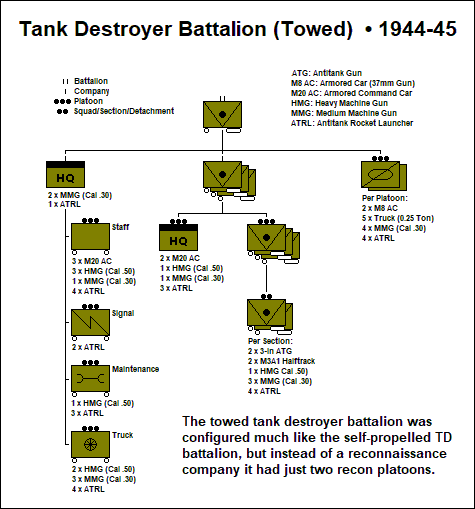

TD

battalions were heavily engaged during the Battle of the

Bulge (December 1944-January 1945)—with mixed results.

Though the self-propelled tank destroyers performed well,

the towed units fared poorly. Guns towed by wheeled prime

movers proved insufficiently mobile to cope with the

Germans’ armored battle groups: Once emplaced they had to

fight it out where they stood, and all too often companies

or whole battalions were overrun. The Army therefore decided

to convert the remaining towed battalions to SP. A few TD

battalions, mostly equipped with the M10, served in the

Pacific. Since Japanese armored forces were minimal, the

tank destroyers served as assault guns.

The end

of the war heralded the end of the Tank Destroyer Force.

The late-war introduction of the M26 Pershing heavy tank, armed with

a 90mm gun, scotched the argument that tank destroyers

provided greater firepower that tanks. A postwar review

concluded that the tank destroyers, though useful, had

performed no mission that could not be performed by tanks. So the TD

battalions were quickly inactivated (though some were to

reappear later as tank battalions) and the Tank Destroyer

Center was closed down in 1946. Such was the unceremonious

demise of an Army branch that whatever its shortcomings had

played a significant and gallant role on the battlefield,

from North Africa to the Elbe River.