● ● ●

With the conclusion of the Battle

of Flanders and the onset of winter, fighting on the Western

Front died down. Both sides were exhausted and frustrated by

the failure of their initial plans. But General Joffre, the

French commander-in-chief, remained steadfast in his

determination to resume the offensive at the earliest

possible moment. Ever the optimist, he was undaunted by the

horrific casualties suffered by the French armies in the

Battle of the Frontiers. The Germans too, he argued, had

suffered heavily and were vulnerable to attack in the great

bulging salient between Arras and Rheims (see map

here). But as

events were to show, Joffre both overestimated German losses

and underestimated the strength of the defense in trench

warfare. The British, whose army in France was slowly

expanding, were of similar mind. On the Allied side there

was no doubt among the military commanders that it was both

necessary and possible to win the war by defeating the

Germans in France and Flanders. As yet only a few isolated

voices—Winston Churchill’s prominent among them—were

suggesting that there might be strategic opportunities

elsewhere.

On the German side, however,

disagreements had already arisen between General von

Falkenhayn, the Chief of the OHL, and the heroes of the

Battle of Tannenburg. Generals Hindenburg and Ludendorff—the

Duo as they came to be called—argued that the vulnerability

of Russia, so plainly evident in the opening round,

presented a golden opportunity. If Russia could be knocked

out of the war Germany would then be free to concentrate

against the Allies on the Western Front, thus guaranteeing

victory.

Falkenhayn disagreed. He doubted

that it was possible decisively to defeat Russia—a huge

country, rich in manpower, whose vast spaces would swallow

up the German and Austrian armies. Despite the

unsatisfactory outcome of the opening campaign in the west

Falkenhayn remained convinced that France and Flanders

constituted the decisive theater of war. Thus originated the

long, acrimonious strategic debate between Germany’s

“westerners” and “easterners.” It was a debate complicated

by the shaky condition of the Austrian armies, which had

been so soundly trounced in the opening round. Much against

his inclination, Falkenhayn was compelled to dispatch

reinforcements to bolster up the Austrian sector of the

Eastern Front. Whatever its military deficiencies, Germany

could ill afford to lose the Austro-Hungarian ally.

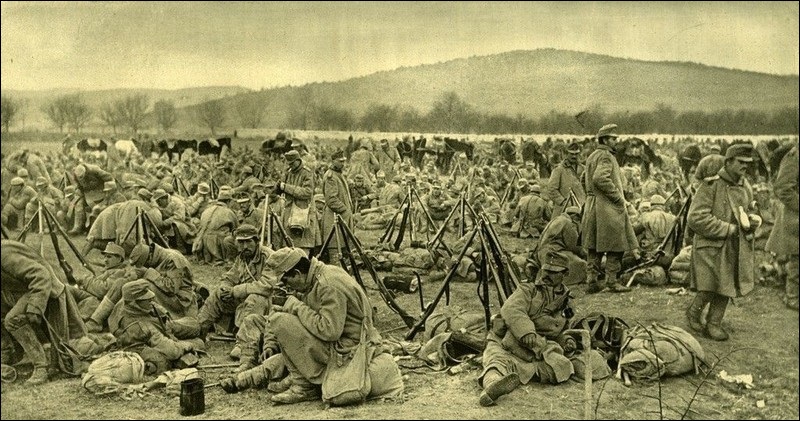

Austro-Hungarian troops on

the Eastern Front, winter 1914-15 (Heeresgeschichtliches

Museum)

Another complication was

Falkenhayn’s conviction that further offensives in the west

would be futile. The Germans’ failure to break through at

Ypres in October-November 1914—though they came close to

doing so—and the high casualties sustained had shaken his

faith in victory by decisive battle. He now argued—and here

the Chief of the OHL was prescient—that the war would last a

long time, that it would be a war of material, and that

attrition would determine the outcome. In effect, he

reverted to the strategy of Ermattungsstrategie,

exhaustion of the enemy.

Falkenhayn therefore set about mobilizing the German economy

for a long conflict. Plans were laid for great increases in

production of machine guns, heavy artillery and munitions.

The allocation of labor, essential raw material and

foodstuffs was brought under control of the War Ministry. By

these means Germany gained a march on the Allies, who were

slower to recognize that fundamental changes in the nature

of war were occurring. Only gradually would it dawn on them

that the Great War was a peoples’ war, with the armed forces

just the spearhead of a mighty national effort.

On the Western Front itself, the

crude entrenchments of the early days were being expanded

and improved, and here again the Germans were ahead of the

Allies. The trenches they dug were deeper, better

constructed and better sited than those of the British and

French. Much thought and effort were devoted to the development

of an integrated defense based on machine guns and

artillery. This was in sharp contrast to the French and,

particularly, the British attitude. When proposals were made

to increase the British infantry’s allocation of machine

guns from the paltry prewar scale of two per battalion to

sixteen per battalion, senior commanders in France were loud

in their objections. General Sir Douglas Haig, commanding

the First Army, argued that the machine gun was “a much

over-rated weapon,” and that two per battalion were more

than sufficient. Field Marshal Lord Kitchener, the Secretary

of State for War, thought that four per battalion would

surely be adequate. Eventually the generals were overruled

but their resistance to a weapon that had more than proved

its worth in the opening round was an ominous portent.

"A much over-rated

weapon": the British Vickers caliber .303 machine gun

(Imperial War Museum)

On the Eastern Front the situation

was rather different. There, thanks to the great length of

the front relative to the number of troops engaged, a war of

movement remained possible. Trench warfare was not unknown

in the east but it never became absolutely dominant, as

happened in the west.

The opening round in the east had

ended in a German victory over the Russians in East Prussia

and a Russian victory over the Austrians in Galicia. These

results intensified a dispute in the Russian military

command that predated the war: Where to place the main

effort? As Germany had “westerners” and “easterners,” the

Russians had “northerners” and “southerners.” The former

advocated placing the main effort against Germany, seen as

the main enemy; the latter argued for placing it against

Austria-Hungary, seen as easier to defeat. The dispute had

not been resolved before the outbreak of the war, so that

Russia conducted two completely separate campaigns in the

opening round—and nobody’s mind was changed by either the

Tannenburg debacle or the victory in Galicia. The

northerners alleged that the invasion of East Prussia had

failed because it was undertaken prematurely, before the

Russian Army was fully mobilized. The southerners offered

the collapse of the Austrian armies in Galicia as proof that

they had been right all along. Again the dispute was not

resolved and the Russian Army continued to fight two

separate wars, with much bickering between the commanders

involved as to the allocation of material and reserves.

A more immediate problem, however,

was a shortage of weapons and munitions—the Russian Ministry

of War and General Staff having greatly underestimated the

rate at which both would be consumed. Prewar stocks were

largely used up in the opening round and production was

quite inadequate to cover requirements—no provision having

been made for a large-scale conversion of industry to meet

wartime needs. The resulting shortages, serious enough in

themselves, also provided the generals with a convenient

excuse for their repeated failures against the Germans. As a

matter of fact the shell shortage as it was called was never

as dire as the generals alleged, and many of the defeats

they sustained at the hands of the Germans could have been

prevented or at least ameliorated by more sensible planning

and tactics.

So as Europe entered the first

winter of the war, the Allies in the west busied themselves

with plans for the offensives of 1915 that would, they were

confident, overthrow the German Army. In the east, Germany

was preoccupied with the necessity of shoring up the

Austrian front in the Carpathians, where continued Russian

pressure threatened a breakthrough into Hungary that would

be disastrous for the Habsburg Monarchy. Falkenhayn,

resigning himself to the inevitable, therefore decided that

in view of the Austro-Hungarian emergency, the main German

effort for 1915 would have to be made in the east. If it

could not be decisively defeated, the Russian Army must at

least be neutralized. To that end, considerable forces were

taken from the Western Front for dispatch to Poland, and the Austrians were browbeaten into accepting a

unified command arrangement for the Eastern Front. As a

first step, Falkenhayn planned a limited offensive, to be

launched in mid-November, with the objective of destroying

Russian forces in the Polish salient.

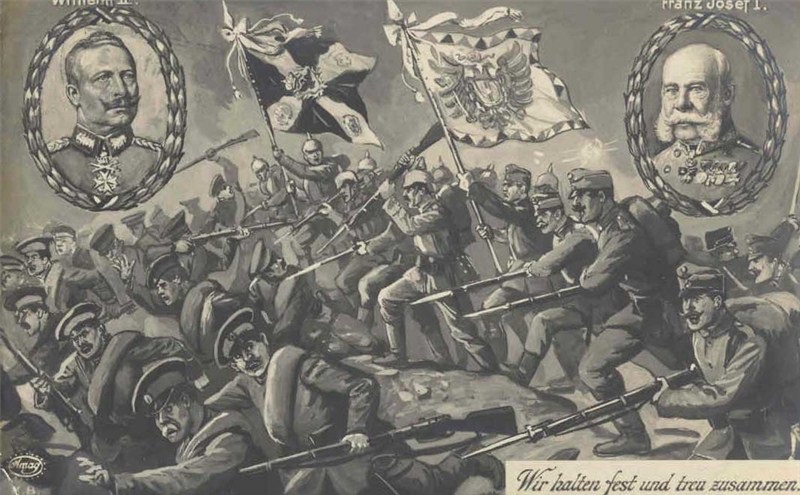

A contemporary postcard

celebrating the Austro-German alliance; the reality was

somewhat different (FirstWorldWar.com)

A complicating factor for the

Central Powers was the possibility—increasingly likely in

view of the Austro-Hungarian emergency—that Italy would

enter the war. That country had bailed out of the Triple

Alliance in August 1914, arguing that Austria’s aggression

against Serbia negated its treaty obligations. And though

the Italian government declared neutrality, its designs on

the Austrian Trentino, Trieste and the eastern Adriatic

littoral were hardly a secret. Italy thus found itself in the

congenial position of soliciting bids for its support in the

war. Germany pressed the Austrians to yield up some

territory in exchange for continued Italian neutrality,

adding in an undertone that after victory it could always be

taken back. The Allies offered to support Italy’s annexation

of the desired territories in exchange for its entry into

the war.

But for the moment the Italians

hesitated; not all political factions in Italy were in favor

of war. By and large the liberal-nationalist government and

its supporters were the war hawks; the socialists and the

conservatives mostly opposed intervention. But with the

string of defeats suffered by the Austrians in Serbia and

Galicia, the temptation to take the plunge grew stronger and

stronger.

Thus as 1914 drew to a close, few

among the belligerents were willing as yet to admit that

militarily the war was deadlocked. With the significant

exception of Falkenhayn, the generals remained confident

that with more troops and more firepower that they could

overcome their difficulties and achieve decisive victory. In

1915, a second round of battles, west and east, would put

that confidence to the test.