No

senior general on the German side in World War II became

better known than Erwin Rommel. He was still a colonel on

the eve of the war and in 1938 was given command of the

Führer-Begleit-Battalion, Hitler’s personal military

escort. The Führer knew Rommel by reputation and looked

favorably on him because he was a fellow combat veteran of

the Great War—a decorated “front fighter” like himself.

Hitler had an interest in promoting the careers of such

officers as a counterblast against the clique of

aristocratic Prussian staff officers who ran the Army, and

whom he disliked and deeply distrusted. Rommel himself was a

Württemberger of middle-class background who did not wear

the silver-embroidered crimson collar insignia and crimson

trouser stripes of the

General Staff. Despite

this, he was promoted to major-general shortly before the

invasion of Poland (1 September 1939).

Thus

Rommel was well positioned to lobby for command of a

panzer division and this he

received at Hitler’s instigation after the Army personnel

office turned his request down, offering him a mountain

infantry division instead. He became commanding general of

the 7. Panzer-Division in time for the invasion of

France (10 May 1940) and his outstanding leadership of the

“Ghost Division,” as it came to be nicknamed, laid the

foundation of his later military reputation.

What is

remarkable is that at the time of his appointment, Rommel

had no particular experience of armored warfare. During the

Great War he’d served as an infantry officer in the crack

Alpenkorps, a mountain infantry division, primarily on

the Italian front. As an infantry company commander he

displayed the qualities of leadership that were later to

serve him so well in France and North Africa: dash, drive,

initiative, an intuitive feel for the battlefield. Rommel

was one of the very few junior infantry officers to receive

Imperial Germany’s highest military decoration, the coveted

Pour le Mérite,

known

colloquially

as the Blue Max. (Another

was the writer Ernst Jünger, author of the Great War

classic, Storm of Steel.)

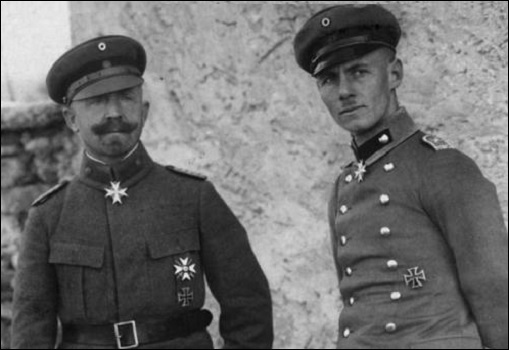

Lieutenant Rommel and a brother officer in

Italy, 1917. By this time he had been awarded the Blue Max

(Weapons and Warfare)

After

the war Captain Rommel was selected for retention in the

Reichsheer, the

100,000-man army allowed to Germany by the Treaty of

Versailles. In 1920 he received command of a company of

Infanterie-Regiment 13, then stationed in Stuttgart, a

post in which he remained for the next nine years.

Subsequently he was posted as an instructor to the Infantry

School in Dresden (1929-33), being promoted to major in

1932. A year later he was promoted to lieutenant-colonel and

given command of Jäger-Bataillon 3 of Infanterie-Regiment

17. In 1934 he met

Hitler for the first time, when the Führer reviewed the

battalion during an inspection tour.

In 1935 Lieutenant-Colonel

Rommel was posted as an instructor to the newly reopened War

Academy in Berlin, where he remained for the next three

years. It was during this time that he wrote

Infanterie greift an

(Infantry Attacks)

a narrative and analysis of his experiences as a Great War

infantry officer that became a bestseller. Among its many

readers was Hitler. The author had already come to the

Führer’s

notice as a gifted instructor and

on the strength of this he had Rommel appointed to the War

Ministry as military liaison officer to the Hitlerjugend

(Hitler Youth) organization. The appointment was not a happy

one. Rommel, the apolitical soldier, soon came into

collision with Baldur von Schirach, the HJ leader, over

training issues. Their disagreements proved intractable, and

in 1937 Colonel Rommel (as he was by

then) was

quietly transferred to the Theresian Military Academy in

Austria as its commandant.

But the HJ interlude did not diminish

Rommel’s

standing in Hitler’s eyes.

In 1938 the

Führer specifically requested his appointment as commander

of the new

Führer-Begleit-Battalion.

During the Polish campaign he accompanied Hitler on his

visits to the front, which gave him an opportunity to

observe the Panzerwaffe

in action. Having been promoted to major-general just before

the outbreak of the war, Rommel knew that he would likely be

offered a divisional command, and what he had seen in Poland

convinced him to request a panzer division.

Yet despite

Rommel’s

special relationship with Hitler, his attitude toward the

National Socialist regime was always equivocal. Without

doubt, he welcomed Hitler’s ascent to

power: As a German officer he had both patriotic and

professional reasons for supporting Hitler’s rearmament program

and foreign policy aims. Though he never became a formal

member of the Nazi Party Rommel was, until a relatively late

stage, a regime loyalist: a man who viewed with approval

much of the National Socialist program. But he

preferred to steer clear of politics—a preference that

became more and more problematical as he advanced in rank.

Unlike

many other senior generals Rommel never served on the

Eastern Front and had no first-hand knowledge of the worst

Nazi crimes. The war in North Africa, though not quite the

chivalrous affair of legend, was conducted by both sides

with a decent respect for the law of war. Yet Rommel cannot have been unaware of

the atrocities committed by German forces elsewhere,

nor of Nazism’s genocidal anti-Semitism. Certainly Rommel

shared some of the anti-Jewish and racial prejudices common

in Germany at the time. But he seems to have been disdainful

of Nazi racist ideology and is known to have expressed sharp

disapproval of the treatment meted out to German Jews in the

years before the war. Even so, the best that can be said of

him in this regard is that he preferred to look the other

way until force of circumstances compelled him to face the

facts.

Rommel with officers of the 7.

Panzer-Division during the 1940 French campaign (Bundesarchiv)

But in

the spring of 1940 all that lay in the future. Commanding 7.

Panzer-Division in the invasion of France and the Low

Countries, Rommel displayed the same dash and decisiveness

that had won him the Blue Max as an infantry officer in the

Great War. But his real moment of glory came in February

1941 when he was promoted to lieutenant-general and made

commander of the Deutsches Afrikakorps,

a small, two-division mechanized corps. The DAK was intended

to bolster up the Italian Army in North Africa, which had

just been soundly defeated by a much smaller British force.

The high command in Berlin enjoined him to adopt a defensive

posture, but this direction and his technical subordination

to the Italian command in North Africa Rommel blithely

disregarded. In March he went over to the offensive with his

small force and in short order the British were bundled out

of Italian North Africa.

There

followed a year and a half of seesaw combat over the Western

Desert, in which the British were repeatedly out-generalled

by the Desert Fox, as Rommel soon became known. “Rommel,

Rommel, Rommel!” Winston Churchill was heard to say during

this period. “What else matters but beating him?” But in

Berlin the North African campaign was regarded as a sideshow

and the Chief of the General Staff, General Franz Halder,

looked with disfavor upon Rommel’s performance. The high

command’s attention was fixed on the Eastern Front, the DAK

was never given the additional forces that might have

enabled Rommel to score a decisive victory, and the Desert

Fox’s run of luck came to an end at El Alamein.

The

final stage of Rommel’s career was melancholy. Though

promoted to field marshal and hailed as a national hero, he

became depressed as the realization grew on him that

Hitler’s direction of the war and the crimes of the regime

were driving Germany to destruction. As has already been

noted, Rommel was not a

political soldier and he preferred to concentrate on his

military duties. But as he rose in rank involvement in

politics became unavoidable. His disillusionment stemmed

from the closing stages of the North African campaign when

for the first time he had to deal directly with Hitler's

military irrationality, and it was confirmed during the Battle

of Normandy in the summer of 1944.

In

November 1943, Rommel was appointed as General Inspector of

Western Defenses. What he found there appalled him: Hitler’s

vaunted Atlantic Wall was little more than a propaganda

myth. An Allied invasion of France in the spring of 1944

appeared inevitable, and Rommel argued to Field Marshal Gerd von

Rundstedt, the

Commander-in-Chief West, and to Hitler that a major buildup

of forces and defenses was urgently necessary. On

Rundstedt’s recommendation, Rommel was appointed to the

command of Army Group B, charged with the defense of the

most likely invasion sites: Normandy and the Pas de Calais.

He tackled the job with characteristic energy but soon found

himself embroiled in a debate over

basic strategy.

Rommel was convinced that the invasion must be defeated on

the beaches by immediately throwing in all available forces;

his superior Rundstedt argued for the creation of a large

operational reserve in readiness to launch a well-prepared

counterstroke once the main objective of the Allied attack became

apparent. Hitler, who had the last word, could not make up

his mind and so split the difference—with fatal results on

D-Day and after.

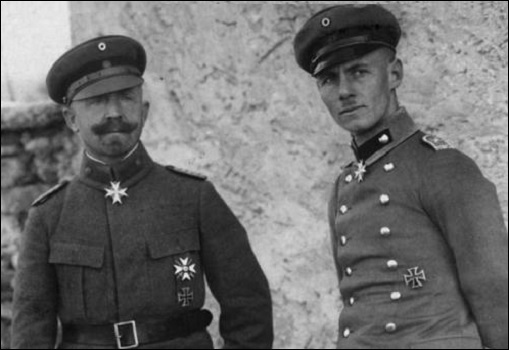

Rommel (right) with Field Marshal von

Rundstedt at the latter's headquarters in

Paris, early 1944

(Bundesarchiv)

Rommel

was absent in Germany on the day of the Allied invasion (6 June 1944), and during the

subsequent Battle of Normandy he never had an opportunity to

repeat his brilliant North African performance. Facing a

greatly superior enemy, hamstrung by

Hitler’s

stand-fast order,

he grew

increasingly pessimistic. When he and

Rundstedt met

with Hitler on 17 June, Rommel was blunt: the unequal

struggle on the Normandy front would end with the collapse

of the German Army and the loss of France. He suggested that

the

Führer should draw the inevitable political conclusions,

implying that Germany must sue for peace. Hitler brusquely

dismissed this advice, telling Rommel to mind his own

business and concentrate on his military duties.

Like

various other generals, then, Rommel turned against his

Führer

when it became clear that the war was lost, though the extent of

his involvement in the 20 July plot to assassinate Hitler

and overthrow the Nazi regime remains unclear. Rommel’s

chief of staff, Lieutenant-General Hans Speidel, was an

active conspirator, however, and it seems likely that

through him the Field Marshal became aware of the plot. Evidence

uncovered in 2018 indicates that Rommel was in contact with

other conspirators as well, and that after some soul

searching he came to the conclusion that Hitler and his

inner circle had to be eliminated.

But

Germany’s most famous soldier was not fated to play a role

in the drama of 20 July 1944. On 17 July the staff car

carrying Rommel was strafed by an RAF fighter-bomber. He was

seriously wounded and on 20 July lay unconscious in the

hospital. Though his doctors expected him to die, Rommel

rallied and eventually was discharged to convalesce at home.

While he languished there, the

Gestapo investigation into the assassination attempt brought his involvement to light. But unlike the other

conspirators Rommel was not dragged before the People’s

Court to be reviled and denounced by its venomous chief

judge,

Roland Freisler.

Hitler feared the consequences that might flow from

the public humiliation and execution of such a national

hero, so instead Rommel was offered an honorable exit.

He would be permitted to commit suicide, thus avoiding disgrace

and protecting his family from retaliation. Rommel agreed to

this and on 14 October 1944 he took the poison provided by

two officers who'd been sent to convey Hitler's offer. The German

people were told that the Desert Fox had died of his wounds;

his funeral and burial were conducted with full military

pomp.

Thus

ended the career of a legendary military figure. In

retrospect, however, it must be said that Erwin Rommel’s record

as a commander is mixed. He was certainly a valiant

soldier and a brilliant tactician but the Desert Fox never

had an opportunity to show what he could do at the highest

level of command. There is reason, indeed, to think that he

lacked the breadth of vision necessary for such a position. Rommel

tended to slight the logistical or administrative

side of war; it was other people's business to provide the

supplies that his troops needed.

He was at his best in a fluid, dynamic situation, leading

from the front, in direct touch with the battle, which was why desert warfare suited him so

well. In Normandy, commanding Army Group B against a greatly

superior enemy, he never had an opportunity to repeat that

performance.

As a

commander of men Rommel certainly possessed a deft touch.

Though he was unpretentious, he had presence and his junior

officers and troops—both German and Italian—were devoted to

him. And though he was critical—sometimes rudely so—of the Italian command, he was generous in his assessment of

the ordinary Italian soldiers who, he said, were not

responsible for the shortcomings of their leadership. When

after a battlefield setback an Italian battalion commander

protested to him, “Please believe me, my men are not cowards,” Rommel replied, “Who said anything about cowards? It’s the

fault of your leaders for sending you into action with such

poor equipment.”

Rommel in North Africa with German and

Italian officers, 1941 (World War II Database)

Many

senior German generals were critical of Rommel, among them

his superior in France, Field Marshal von

Rundstedt.

Perhaps influenced by their dispute

over strategy, he

opined to the British military historian B.H. Liddell Hart

in a postwar interview

that the Desert Fox,

though undoubtedly a soldier's soldier,

was in over his head as an army group commander. Rundstedt

added, however, that

despite their disagreements

Rommel had been a loyal subordinate:

“When

I gave him an order, he carried it out without making any

difficulties.”

Perhaps the closest counterpart to

Rommel among the senior Allied generals was General George

S. Patton, another great fighting soldier who served at a

level below the summit of command. Though Rommel displayed

none of Patton’s self-conscious flamboyance and showmanship, he took the

same cut-and-thrust approach to armored warfare.

“L'audace,

l'audace, tojours l'audace,”

as Frederick the Great put it. Both Rommel and Patton

followed the King's advice.

But let

the last word on Erwin Rommel rest with Winston Churchill:

His

ardour and daring inflicted grievous disasters upon us,

but he deserves the salute which I made him—and not

without some reproaches from the public—in the House of

Commons in January 1942, when I said of him,

“We

have a very daring and skilful opponent against us, and,

may I say across the havoc of war, a great general.” He

also deserves our respect because, although a loyal

German soldier, he came to hate Hitler and all his

works, and took part in the conspiracy of 1944 to rescue

Germany by displacing the maniac and tyrant. For this,

he paid the forfeit of his life. In the sombre wars of

modern democracy chivalry finds no place.

The Second World War Volume III: The Grand Alliance