In the late summer of 1939, with war

in sight, the German Army’s senior commanders were in no

confident mood, the Oberkommando des Heeres (OKH or

High Command of the Army) being all too well aware of the

Army’s deficiencies. To be sure, the crash rearmament

program embarked upon in 1935 had greatly increased the

Army’s size. In 1933 the

Reichwehr,

as the Army was then titled, had just seven infantry

divisions and three cavalry divisions. Now there were 85 infantry divisions, three mountain infantry

divisions, four motorized infantry divisions, seven panzer

(armored) divisions and four light mechanized divisions,

plus various brigades and independent regiments.

But of the 85

infantry

divisions, only those of

the 1st Wave, thirty-five in number, were substantially up

to strength. The other 50—those of the 2nd, 3rd and 4th

Waves—lacked many items of equipment. None had any 50mm or

81mm mortars, 20mm antiaircraft guns or 150mm heavy infantry

guns. The divisional artillery regiments were mostly

equipped with older or captured Czech weapons. In partial

compensation for these deficiencies the 3rd Wave divisions

did receive a higher allotment of machine guns but they too

were often older or captured models. Due to a shortage of

motor vehicles, the motorized elements of many infantry

divisions were actually horse drawn.

As for manpower, the 1919 Peace

Treaty’s prohibition of conscription had, as intended,

prevented the buildup of fully trained military reserves.

The 51 divisions of the 1st and 2nd Waves had the

highest percentages of active soldiers and Class I

Reservists, the latter being conscripts who’d served with

the colors for one or two years after conscription was

restarted in 1935. These divisions were considered fully

trained and fit for active service but even so many of them

were short of technical specialists and trained staff

officers.

The twenty divisions of the 3rd

Wave were the peacetime army’s Landwehr

(militia) divisions. Their personnel were older men, many of

them First World War veterans. Upon mobilization the

Landwehr divisions

were filled out with Class II Reservists. These men, born

between 1901 and 1913, were too young to have served in the

First World War, nor had they received any military training

in the Weimar years. Beginning in 1935 they’d been called up

for two or three months of basic military training—the bare

minimum. The fourteen divisions of the 4th Wave were set up

in early 1939. They also consisted mostly of

Landwehr men and Class

II reservists. To compensate for their lower state of

training the 3rd and 4th Waves divisions were given a

simplified organization and OKH planned to use them

mainly for static defense in quiet sectors.

Command flag, Oberbefehlshaber des

Heeres (Commander-in-Chief of the Army)

As for the mobile forces—the

panzer divisions, light mechanized divisions and

motorized infantry

divisions—they too were beset by various equipment and

manpower deficiencies. Many of the available tanks were

Panzer Is, originally intended for training and armed only

with machine guns, and Panzer IIs, armed with a 20mm gun.

The two models intended to be the panzer divisions’

mainstays, the Panzer III (37mm gun) and the Panzer IV (75mm

gun) were, due to production bottlenecks, in very short

supply. Former Czech Army tanks—of sound design, armed with

a 37mm gun—were therefore pressed into service. The panzer

divisions’ motorized infantry regiments were supposed to be

equipped with armored halftracks, but scarcely any were

available and trucks were substituted. However, since,

industry was unable to produce sufficient trucks to meet the

Army’s needs, many civilian trucks had to be requisitioned.

The mechanized divisions were also short of various

specialized armored vehicles: command tanks, armored command

cars, armored radio cars, etc.

The four light mechanized divisions

had been conceived as the mechanized successors to horse

cavalry formations. However, peacetime maneuvers revealed

that with just one battalion of tanks they lacked hitting

power. Plans were accordingly drawn up for their conversion

to full-fledged panzer divisions, but this could not be

completed before war broke out.

OKH judged that in the event of war

it would be necessary to commit all the mechanized divisions and

the bulk of the infantry divisions against Poland. Only

24 infantry divisions were allotted to

HG C, defending Germany’s western frontier. Clearly, so

meager a force could do little more than delay the prompt

French offensive that OKH expected—though its anxieties on

that score were somewhat eased by the Nazi-Soviet Pact,

which foreclosed the possibility of Red Army intervention in

support of the Poles. It was hoped that the Polish campaign

could be concluded quickly, so that forces could be released

for HG C before the French Army opened its offensive.

The mobilized German Army was

disposed in three army groups: HG C in the west,

HG Nord (North)

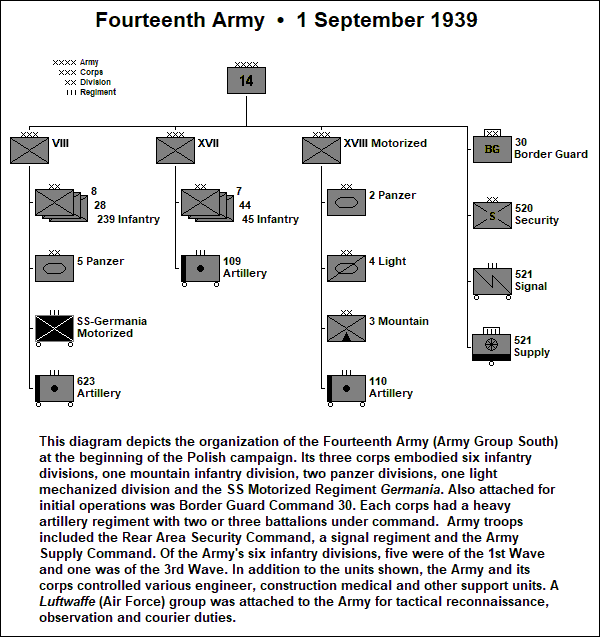

and HG Süd (South) against Poland. Each army group commanded a

number of field armies and each field army commanded a

number of corps. Divisions were assigned to the corps in

accordance with the operational plan. In addition to their

assigned divisions, corps had a variable number of

non-divisional artillery, engineer other support units.

Reserves were mostly held at army group level, AG South for

example having eight divisions and two corps headquarters

available. Further reserves were at the disposal of OKH. For

example, eleven of the fourteen

4th Wave divisions

were stationed in the HG C sector as OKH reserves.

September 1939: German troops demolish a

Polish frontier barrier (Bundesarchiv)

At the beginning of

the war, the Commander-in-Chief of the Army was

Colonel-General Walther von

Brauchitsch;

the Chief of the General Staff was General of Artillery

Franz Halder. Both men had been appointed in the wake of the

Blomberg-Fitsch Affair, which Hitler had exploited to rid

himself of critics in the senior ranks of the Army.

Brauchitsch, a respected figure in Army circles, was beholden to

Hitler for financial assistance given in the course of an

acrimonious divorce. Halder was a competent staff

officer, a Bavarian of middle-class background rather than a

Prussian aristocrat, no great admirer of National Socialism,

but a prey to indecision when it came to political issues. Neither man was to prove himself capable of standing up

to Hitler in the time of crisis now impending.

Even so, OKH could still claim a measure

of autonomy. Case White (Fall Weiss), the operational

plan for the invasion of Poland, was drawn up by OKH with

little interference from Hitler or the Armed Forces High

Command (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht or OKW). The

actual conduct of operations also remained in OKH’s hands.

And the rapid success gained against the gallant but

outclassed Polish Army might have been thought to reinforce

the prestige of the Army leadership.

But trouble lay on the horizon. The

British and French declarations of war on Germany were a

considerable shock to the generals, many of whom had shared

Hitler’s hope that the Western Allies would flinch from the

prospect of war. And they were dismayed when, with the

conclusion of the

Polish campaign, the Führer began pressing for an immediate

attack in the West. As far as

Brauchitsch and Halder were concerned, this was

madness—and there were many other senior officers who shared

their opinion. The fighting in Poland had revealed numerous defects in

the organization and training of the German Army—the

headlong pace of rearmament having been accompanied by many

growing pains. Thus OKH argued that no

attack in the West should be attempted before the spring of

1940 at the earliest. But Hitler insisted otherwise and this

dispute poisoned his mind against the Generalität.

He judged the Army's senior commanders to be unimaginative,

timid and insubordinate, an attitude that was to develop

into a mania as the war proceeded. Ultimately, however, it

was the weather—the winter of 1939-40 was exceptionally

severe—that settled the issue by compelling Hitler to put off the offensive

until spring.

At this point there occurred a series

of events that constituted, for OKH, an ominous portent of

the future. In November 1939 the USSR launched an attack on

Finland, and the subsequent Winter War disrupted the

delicate network of relations between Germany and the

neutral Scandinavian countries. The Nazi-Soviet Pact

concluded just before the invasion of Poland excluded

Finland from the German sphere of influence, thus requiring

Germany to maintain a neutral attitude toward the conflict.

But this was ill received in the other Scandinavian

countries, where public opinion strongly supported the Finns—who

stoutly and for a time successfully resisted Soviet

aggression. Meanwhile Hitler began to grow fearful of a British and French incursion into

northern Norway and Sweden, using assistance to Finland against the USSR as

a pretext. The Allies' actual aim, he thought, would be to

cut off Germany's vital

supply of Swedish iron ore—much of which was transported by

ship through Norwegian territorial waters. And in this he

was not wrong, though the end of the Winter War

scotched the Allied plan. Nevertheless, the Führer decided on

preemptive action: a swift invasion and occupation of both

Denmark and Norway.

This operation—Weserübung

(Exercise Weser)—was launched in April 1940 and proved

stunningly successful. But Hitler had short-circuited OKH

entirely, allowing it no hand in the planning or conduct of

the operation. He was probably right to conclude that

Brauchitsch, Halder and company would

make difficulties over such a high-risk venture, so he

established a special cell within OKW to draw up the plan

and supervise its execution. This was the first time that OKH had

been definitely excluded from any role in a major military operation.

When the offensive in the West was

finally launched in May 1940, it too was a stunning success—but

once again OKH suffered a setback. The original operational

plan for Fall Gelb (Operation Yellow) was thought by

some to be unimaginative—virtually a rerun of the

1914

Schlieffen Plan—and

unlikely to produce decisive results. The postponement of

the attack gave time for the dissenters to make their case,

ultimately to Hitler, and he sided with them. The Manstein

Plan, as it came to be called after its primary author,

exploited the capabilities of airpower and the panzer forces

to defeat the French, British, Belgian and Dutch armies in

less than two weeks. But in a sense it was also a defeat for OKH, whose credibility was further diminished in Hitler's

eyes.

It was undeniably true that in

1939-40 the German Army was unprepared for a general European war—a war that

Hitler had assured the Generalität would not come before

1944-45. Its basic combat units, the infantry divisions,

were variable in quality, its mobile units had not yet

reached the desired standard of armament and organization,

and industry was unprepared to meet the wartime needs of the

armed forces.

Nor were existing reserves of munitions, fuel and other supplies

sufficient to support the armed forces for a prolonged

period. Thus OKH felt justified in counseling caution. But

the Army’s run of victories in 1939-41

papered over all these deficiencies, undermined the

credibility of the senior generals, and further bolstered

Hitler's confidence in his own military judgments—a

combination of factors that in the long run proved fatal to

Germany.